Mark Hillsdon reports on how the vast majority of financial institutions that have signed up to net-zero goals are continuing to invest in companies with deforestation in their supply chains

Deforestation caused by commodities such as soy and beef accounts for 10% of global CO2 emissions, a figure greater than that of the aviation sector. Yet despite a host of pledges and initiatives, finance continues to flow into companies with links to habitat loss and destruction.

Released in the run-up to COP27, Global Canopy’s new Deforestation Action Tracker showed that of the 557 financial institutions that had signed up to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) a year earlier, only 17% had even recognised deforestation as a risk.

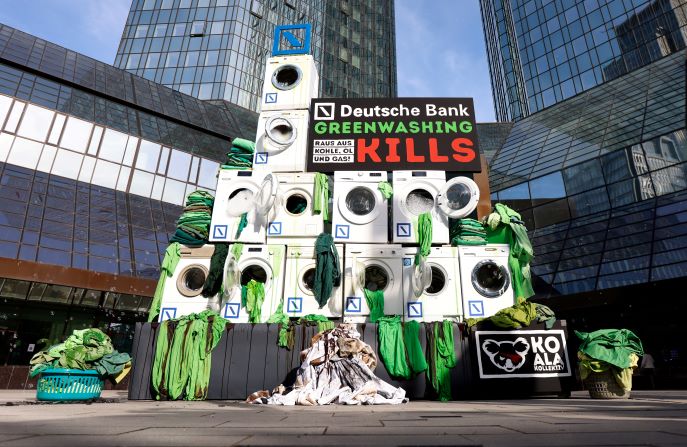

Global Witness said it had further evidence of this “head-in-the-sand” approach when it revealed that several of the big names that are part of GFANZ, including BlackRock, Vanguard and Deutsche Bank, were still investing in companies linked to deforestation.

There are a lot of financial institutions that have not thought about the deforestation that they are exposed to

Most damming, said Global Witness, was the fact that GFANZ members had acquired an additional 10 million shares in Brazilian meat giant JBS since COP26, with Vanguard alone increasing investments by an estimated $12.4 million.

JBS has long been associated with accusations of deforestation, although it was one of the companies that unveiled a roadmap at COP27 to eliminate commodity-driven deforestation, while in the latest report from FAIRR, the investor network focused on ESG risk in the food sector, the company was only classed as being at medium risk of deforestation.

Asked about these developments, Veronica Oakeshott, forest campaign lead at Global Witness said: “We regard JBS’s participation in the roadmap as a dead end. The company has signed up to many such voluntary agreements in the past and failed to deliver on them. We have been investigating their murky supply chains for years, and year after year we find illegal deforestation and human rights abuses. So this latest promise rings hollow.

“Transparency from JBS about who it buys its cattle from, and how it monitors those suppliers for deforestation, would be far more helpful than road maps. In terms of its deforestation and human rights record, JBS has long run out of road.”

In September, GFANZ leaders wrote to members urging more institutions to join the 30 that last year signed a Commitment on Eliminating Commodity-driven Deforestation from their portfolios. “In our view, transition plans that lack objectives and clear targets to eliminate and reverse deforestation are incomplete,” the letter said. By COP27, the number of signatories had only risen to 35.

“There are a lot of financial institutions that have not thought about the deforestation that they are exposed to,” says Sarah Draper, Global Canopy's corporate performance programme manager. Some put it down to a lack of information, she says, but many are also knowingly continuing to invest.

It’s not possible to reach net-zero without tackling deforestation. It needs to be explicit in climate strategies

Draper says she has been told by companies with net-zero commitments that their focus is on climate and don’t have the resources to think about deforestation as well, even though the two are inexorably linked. “It’s not possible to reach net-zero without tackling deforestation… (it) needs to be explicit in climate strategies,” she says.

A lack of data is often cited as a reason why deforestation risks haven’t been properly assessed, continues Draper, but information is freely available to help investors find the most exposed companies in their portfolio.

Global Canopy’s own Forest 500 uses publicly available company data to identify organisations with the greatest exposure to deforestation risk. Investors like Norwegian-based Storebrand use the tool to assess how aware potential investees are of the risk of deforestation, and what they doing to address it, explains Vemund Olsen, a senior analyst in sustainable investments at the company.

Another tool is Trase, a data-driven transparency initiative that maps supply chains. “Trase uses trade documents to monitor which companies are selling and buying commodities from areas where deforestation is high,” continues Olsen. “It gives you an idea of the impact of the companies, but it stops at the point of first import. So, it will tell you who imports the most high-risk soy (for example) ... but then that soy moves through various manufacturing processes before it ends up in the supermarket.”

Next year, Global Canopy is launching Forest IQ, which combines Forest 500, Trase and ZSL Spott data to assess key companies in timber, paper, palm oil and rubber supply chains. By bringing all the data together in one place it will be easier to map the companies, explains Draper, and help investors to deliver deforestation-free portfolios.

Another initiative launched at COP27 was Finance Sector Deforestation Action (FSDA), a member organisation with a focus on using engagement to eliminate deforestation from key agricultural soft commodities by 2025.

You can't transform an ecosystem as large and complex as this without engagement

The FSDA has published shared investor expectations for companies, explains Olga Hancock, deputy head of responsible investment at asset managers the Church Commissioners for England. “You can't transform an ecosystem as large and complex as this without engagement,” she says. “We want to influence them so we can invest with less risk.”

FSDA has now written to all the companies listed in the Fortune Global 500, she continues, detailing their expectations. These include setting a public commitment to be deforestation-free by 2025, tracing suppliers in their supply chain and giving time and resources to collaborative actions.

Global Canopy has also produced a Finance Sector Roadmap, which sets out a six-phase approach to address deforestation risk, beginning with mapping risk before moving through monitoring and engagement. “Companies get more leverage by staying invested, so we advocate an engagement-first approach, but there needs to be the threat of divestment,” explains Draper.

Disinvestment is something that Storebrand’s Olsen has had to consider. The company, which has committed to be deforestation-free by 2025, invests in 4,500 companies around the world. “Most of our exposure to deforestation will not be in the companies that are present in the forest and cutting down the trees. We will be exposed through larger companies that buy commodities produced on deforested areas,” he explains.

“We have a blanket ban on coal, and that you can easily test by looking at data about how much of the company’s revenue comes from coal,” he continues. “The issue with deforestation is that it’s a negative side effect of legitimate production.”

That makes it more challenging for financial institutions to understand their role, their exposure and the financial impact it could have.

In December 2021, Storebrand placed U.S. agricultural traders Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) and Bunge on its observation list after deeming their efforts to eliminate deforestation risks from their supply chains as insufficient. Both companies have been asked to implement full traceability of their supply chains to farm level, and commit publicly to not sourcing from suppliers that have converted land since 2020.

Realistically, we have a better chance of succeeding by engaging with governments

The observation list is “an escalation of regular dialogue,” says Olsen. “You are very close to being excluded, but we do think you have the opportunity to speed up your implementation of polices.”

Companies stay on the list for two years and must show “verified progress” to come off it, he explains. Investment is capped at the current level until changes are made.

But others have been dropped, he says, including palm oil plantations and most recently JBS “because we feel they are persistently linked to deforestation in their supply chains,” says Olsen.

“One of the expectations that we have of companies is that they disclose how much of the commodities they use is verified deforestation-free – how much can be traced back to the point of production,” he explains. “If they (the buyers) were to refuse to accept any commodities potentially linked to deforestation, we think that would make a big change in how the farmers operate.”

But working with businesses can only achieve so much, concedes Olsen. “Realistically, we have a better chance of succeeding by engaging with governments,” he says, and points to new EU regulations on deforestation which will demand that companies can trace commodities right back to where they were grown. The UK also has laws to require that commodities weren’t grown on land from illegal deforestation.

Some NGOs, including Global Canopy, argue that while such legislation is to be welcomed, the financial sector should be included in the new rules. In an open letter to the European Commission, nine financial institutions, including Triodos Bank and the ASN Bank, called on the EU regulators to reverse this decision, citing the failure of voluntary regulations to make a noticeable difference to the sector.

Nevertheless, Olsen believes that new regulations will have an impact by speeding things up, forcing the whole market to act rather than relying on individual engagement with companies, which can be a slow process.

Rules need to apply to everyone in order to ensure a fair marketplace

There needs to be a level playing field, he says. “If we engage with a soy-trading company and they agree to improve their transparency, traceability and efforts to avoid deforestation, that will require a lot of money and resources … but their competitors that do not commit to end deforestation can sell at lower prices and gain an unfair competitive advantage.

“Rules need to apply to everyone in order to ensure a fair marketplace, and that will be an incentive for more companies to take action against deforestation.”

And that’s the crux, he says. “Far too few investors are prioritising this issue… we really need many more financial institutions to join this push to end deforestation.”

Mark Hillsdon is a Manchester-based freelance writer who writes on business and sustainability for The Ethical Corporation, The Guardian, and a range of nature-based titles including CountryFile and BBC Wildlife.

This article is part of the Winter 2022 in-depth Financing the Transition briefing. See also:

Reality bits as finance firms row back on their climate pledges

‘Get the blend right’ and we can unlock billions in finance for Global South

Pact to decarbonise heavy industry through corporate purchasing power picks up steam

Can fossil fuel industry sell world on ‘net-zero oil’?

Energy crisis boosts drive to cut emissions from buildings

From climate-smart farming to electric rickshaws: investors look to make an impact

ESG: The investment world’s troubled teen is forced to grow up

Calls grow for companies to disclose nature impacts in bid to plug finance gap

Needed: a sea-change in climate finance for oceans

Comment: To plug the green economy data gap we need regulators to mandate climate reporting

Comment: How companies can lead to make the energy transition work for people and planet