Comment: Matthew Spencer of IDH says if the EU works with producer countries and commodity companies to implement deforestation-free rules, the results could be transformative

As the economic storms of food and fuel price inflation gather pace, deforestation has disappeared from the international headlines. But behind the scenes, there is frenetic activity by international commodity companies and regulators to prepare for one of the biggest shifts in supply chain rules for decades: the new European Union regulation on deforestation-free products.

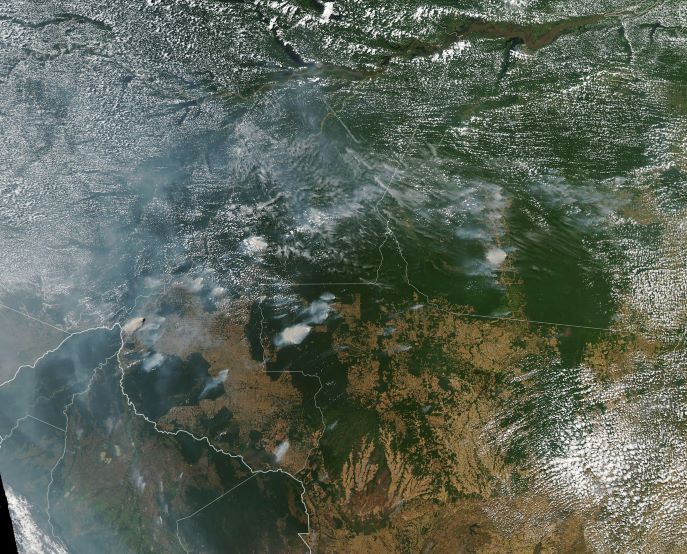

This relatively low-profile agreement will shift Europe from a voluntary to a regulatory approach to reducing the deforestation footprint of commodities such as palm oil, soya and cocoa. It reflects widespread frustration that after decades of concerted effort to support forest protection and agricultural certification, deforestation remains stubbornly high, particularly in tropical forest areas, where over 3 million hectares of primary forest were lost last year. The heat is on to find new tools to exert market pressure because this forest clearance is linked chiefly to agricultural expansion, and Europe remains the second biggest importer of agricultural products linked to deforestation after China.

The new deforestation regulation, which is part of the European Green Deal, is an attempt to side-step the sovereignty arguments that have dominated international negotiations on forest loss. It sets trade standards for EU imports and requires commodity importing companies to work out which of their sourcing areas can meet the standards of traceability and verification of zero deforestation. The regulation will probably not come into force until 2024, but it has already unleashed a huge wave of activity from traders and buyers to map their production to farm-plot level and improve their traceability systems.

Campaigners have high hopes that traceability will end the blame shifting between companies and governments

Inevitably this means that the small number of satellite-monitoring companies are being paid many times for deforestation data from the same areas, but in countries where national monitoring systems are not yet mature enough, companies feel they have little choice.

The campaigners who have made traceability their lodestar have high hopes that it will end the blame-shifting between companies and governments. There are, however, grounds for caution in assuming that these huge investments in mapping will resolve the issues of accountability for deforestation.

Satellite monitoring without extensive ground truthing is unreliable, it does not provide information on deforestation drivers, and laundering of products across farm boundaries is common in beef, cocoa and palm sourcing areas.

The reason it is hard for companies to get to zero deforestation using mapping and verification alone is that the link between commodity imports and deforestation is nearly always indirect. It is now less common for forests to be cleared for plantations or giant ranches, and it is usually land-grabbing by criminal enterprises or encroachment by impoverished smallholders that degrade and destroy the forests of the Amazon, west Africa and the Congo basin.

But many of these areas are just over the boundaries of the farms where international companies are sourcing, and yesterday’s illegal deforestation is often today’s sourcing area.

The answer to this challenge for both commodity companies and the EU is to make sure they balance their farm mapping investments and traceability requirements with partnership to slow and stop forest loss on the ground in the many production areas that are trying to enforce forest law and offer smallholders routes to sustainable production.

Whether this big pulse of corporate action reduces deforestation will depend on how the EU implements its regulation

There are encouraging signs that commodity buyers are willing to do this. Jurisdictional and landscape approaches to sustainable sourcing have won new backing from the Consumer Goods Forum, and members of its Forest Positive Coalition have committed to matching their sourcing footprint with landscape commitments.

There are well over 50 landscape initiatives in Asia, Africa and Latin America that already allow farmers and commodity buyers to produce better, and many have backing from international buyers. They allow companies to contribute to wider landscape efforts to strengthen sustainable land use and reduce the risk that their monitoring system is showing zero deforestation in their source farms whilst it is occurring all around them.

It also offers the prospect of capturing some bigger carbon and nature value in their supply chains because it can integrate environmental benefits from better agriculture with much bigger gains from forest protection. Indeed, COP26 saw the launch of the largest ever public-private effort to protect tropical forests, and it takes an explicitly jurisdiction approach to carbon finance. The LEAF Coalition has generated forward commitments to buy more than $1bn of high-integrity forest carbon credits from the jurisdictions that successfully achieve zero deforestation.

Whether this big pulse of corporate action reduces deforestation will depend on how the EU implements its regulation, as well as how producer governments implement their forest laws. If the EU regulation is applied with a heavy hand, it will make companies more risk-averse, and they will move to “safe” sourcing areas that have been deforested decades ago. In parallel, producer governments will encourage exporters to supply growing demand in Asia, where there are no import restrictions.

But if the EU engages producer governments in their own plans to get to zero deforestation and uses the regulation as part of efforts to incentivise company investment in hotspot landscapes, then it will help turn the tide in production areas bordering our last great forests.

It would allow companies to go beyond “cleaning” EU supply to positively influencing entire forest- risk supply chains. Amidst the current grim economic and climate outlook, that would be a remarkable achievement.

Matthew Spencer is global director, landscapes at IDH - The Sustainable Trade Initiative, overseeing a business unit that includes regional landscape teams in Asia, Africa, Latin America, a landscape finance team and a markets team. He previously worked as strategy director for Oxfam and director of Green Alliance.

Main picture credit: Ricardo Moraes/Reuters

This article is part of our in-depth Autumn 2022 Regenerative Agriculture briefing. See also:

Regenerative EU sows seeds for farming revolution, but will they grow?

Nature-depleted UK sets sights on greener food system post-Brexit

The pioneers trying to restore life to America’s stressed soils

From hemp to Kernza, the hunt for more resilient food crops

Winemakers turn to sustainability to ride the climate storms

Beef and dairy farms pushed to innovate to tackle methane emissions

Turning cows from climate criminals to heroes with agroforestry

Millions of smallholder famers key to fighting growing desertification in Africa

Should we be betting the farm on biochar?

Can sustainable soya farming come fast enough to save the Cerrado?