US land bureau under pressure from surging solar

A lack of local approval capacity is delaying solar build as the Bureau of Land Management scrambles to increase staff count and process priority projects.

Related Articles

A year ago, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced plans to speed up solar development on federal lands, pledging to reduce land rates, streamline project screening and expand approval teams.

The move aims to accelerate renewable energy deployment as attractive sites on commercial land become occupied and dwindling grid connection capacity delays projects. The Biden administration aimed to permit 25 GW of renewable energy on federal lands by 2025 and by March 2023 it had approved 8.2 GW of projects, mostly solar, data from the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management (BLM) shows.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act has stimulated solar and wind activity and the federal land objectives represent a significant challenge for the BLM.

Developers continue to report delays in permitting, despite an expansion of BLM resources over the last year that BLM says has already led to "increased efficiencies” in environmental reviews and project approvals. The bureau is currently conducting environmental reviews for four solar projects for around 2 GW of capacity, along with two wind projects for around 1.2 GW.

The BLM implemented standardised screening of applications to prioritise projects with the "greatest technical and financial feasibility" and last year opened a national coordination office along with four regional coordination offices in Arizona, California, Nevada and a joint office for Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Approval processing will continue to improve as staffing levels increase, a BLM spokesperson told Reuters Events.

In Nevada and Texas, developers are finding the length of the approval process differs depending on the field office involved, Chris DePodesta, Principal, Advisory & Development Services at Stanley Consultants, told Reuters Events.

The cause of the delays can be difficult to identify, making it hard to rectify on future projects, said Devon Muto, Senior Director of Solar Development at EDF Renewables (EDFR). The company is at various stages of development on federal land in California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Utah and its completed projects include the Palen solar project with 620 MW solar and 50 MW storage capacity in Riverside County, California.

The BLM needs to set more time limits on individual processing phases, beyond the 12-month time limit set for environmental impact statements, Muto said.

Land costs

The 245 million acres of U.S. public land managed by the BLM represent around 10% of the country's entire land area but host just 6% of national installed solar capacity and only 1% of wind, according to data in 2022. Much of the land lies in 12 western states and the Rockies, with Southwest states like Nevada offering significant project opportunities.

Recent BLM approvals include Oberon Solar, a 500 MW solar and 500 MW battery storage project in Riverside County, California.

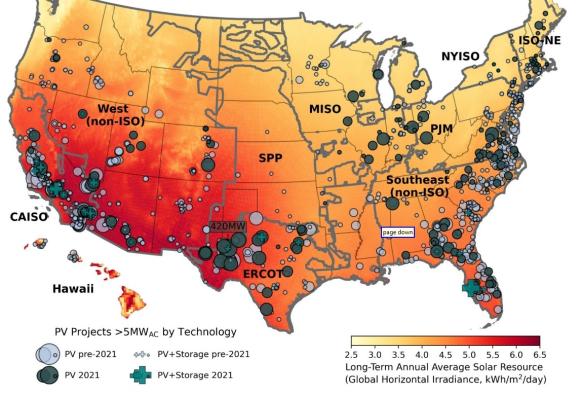

U.S. utility-scale solar installed by end of 2021

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: Berkeley Lab, September 2022

Developers prefer land near transmission lines or substations, of less than 5% gradient, and near logistical infrastructure such as roads and railways.

Land costs have deterred some developers. Last year, BLM revised federal rental rates and extended lease terms after developers said current terms lead to higher project costs than on farmland and other locations.

Land rates are now "more comparable" to rates on private rural land but the characteristics are often different, Muto said. Federal land sites are often less flat and wilder, increasing project costs.

Developers must also pay federal royalty fees, known as megawatt capacity fees, so total land costs are sometimes “far higher than fair market value" in areas such as California’s Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego counties, he added. Solar industry officials have called for the scrapping of the fees.

Priority areas

Meanwhile, the BLM plans to expand the area in its Western Solar Plan (WSP) that aids developers by offering a combined environmental impact statement.

Last updated in 2012, the existing plan includes areas in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico but it is not well coordinated with transmission infrastructure and this limits the benefits for developers, Muto said.

The revised version will also include areas in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming and will factor in planned transmission corridors, advances in solar technology, and the Biden administration’s renewable energy goals. The BLM is also considering whether to lift certain restrictions on flat land areas.

A public comment period for the new plan ended on March 1 and the BLM has already ruled out the inclusion of areas within the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) that spans 22 million acres in California.

"The BLM continues to believe the DRECP supports an acceptable balance between conservation and renewable energy opportunities within its planning area boundary," the BLM said in a statement on February 28.

Restrictions are tighter within the DRECP but the BLM is considering whether to designate more land within it to renewable energy projects. Only 388,000 acres in the DRCEP have been categorised as Development Focus Areas (DFAs) and prioritized for renewable energy development. According to law firm Perkins Coie, only three solar projects with combined 900 MW capacity had been authorised by the BLM in the DRCEP by the end of 2022.

"Projects filed within DFAs must still navigate the BLM’s approval process and address numerous restrictions contained in the DRECP as well as various other regulations," Muto noted.

These hurdles can limit the development area or "require costly mitigation," he said.

Reporting by Neil Ford

Editing by Robin Sayles