While business reaction to the long-awaited strategy was mainly positive, there are fears of a rift in government over finance, and concerns that the low-carbon heat strategy will not do enough to wean the nation off gas boilers, reports Angeli Mehta

With just a week to go till the COP26 climate summit, the UK government will hope that its long-awaited net zero strategy demonstrates the kind of ambition needed to inspire others to lay out their plans of action.

Although the 368 page document left some key questions unanswered for many in industry and the environment, the strategy has been largely welcomed. As Sir John Armitt, chair of the National Infrastructure Commission, put it “the priority now is to get on with it”.

The commitments made will secure 440,000 ‘well-paid’ jobs and leverage £90bn in private investment by 2030

There will be a zero-emissions vehicle mandate for manufacturers and funding to expand electric vehicle charging infrastructure and develop supply chains for electric vehicles – although ministers seek to avoid a “car-led recovery”. (See also Three ways to get the UK's electric vehicle revolution on the road) There’s investment in sustainable aviation fuel, with plans for a 10% mandate by 2030 (which has been panned as not nearly ambitious enough). On the environment, government is committing to treble tree-planting rates, and increase spend on peat restoration – although only a fraction of degraded peatlands will be restored by 2050.

The commitments made will secure 440,000 “well-paid” jobs and leverage £90bn in private investment by 2030, the business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, said. Although full decarbonisation will require hundreds of billions in investment, the UK will get a competitive edge in the new green economy: “The countries that capture the benefits of this global green industrial revolution will enjoy unrivalled growth and prosperity for decades to come.”

In contrast to the stress on job opportunities by the business secretary, the Treasury’s analysis (published alongside) was a more sombre affair. It said action on decarbonisation is “part of the government’s commitment to strong public finances”, but it raised concerns about carbon leakage if companies move to countries with less ambitious decarbonisation agendas; and the loss of fuel and vehicle excise duty – which raised £37bn last year – as drivers switch from fossil fuels.

Carbon taxes alone won’t plug the gap, so any additional public spending on decarbonisation might mean changes to existing taxation and “new sources of revenues”.

Given recent high levels of borrowing, that’s not a “complete surprise” suggests Ana Musat, head of policy at Aldersgate Group, but “there does need to be a clear collaboration between Treasury and BEIS, because I think [what] could be really damaging to market confidence is a perceived rift where one department is pulling in one direction, and the other is trying to do something else.”

But she added that the UK Infrastructure Bank “is going to play a really important role in crowding in investment in areas where we see market failures, for example, energy efficiency, or newer sectors of the economy like hydrogen and CCS that still needs some investment”.

Against the backdrop of the continuing gas crisis, ministers want a clean grid by 2035. The pace of change will require £280-£400bn public and private sector investment for generation capacity and flexible assets. A commitment for 40GW offshore wind by 2030, which could support up to 60,000 jobs, is restated. The sector will get £380m support to develop infrastructure and supply chains.

Industrial decarbonisation needs to be well under way by 2035, with emissions down by 43-53% from 2019 levels

Nuclear will play a part. There will be a final investment decision on at least “one large scale project” by 2024 (negotiations are underway on Sizewell C in Suffolk). A new £120m future nuclear enabling fund is being launched to keep options open for future technologies such as small modular reactors.

Industrial decarbonisation needs to be well under way by 2035, with emissions down by 43-53% from 2019 levels. At least £14bn of additional public and private sector investment will be required.

Carbon capture is going to play a bigger role than envisaged earlier this year – with the government aiming for the annual removal and storage of 20-30m tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2030, including 6m tonnes of industrial emissions.

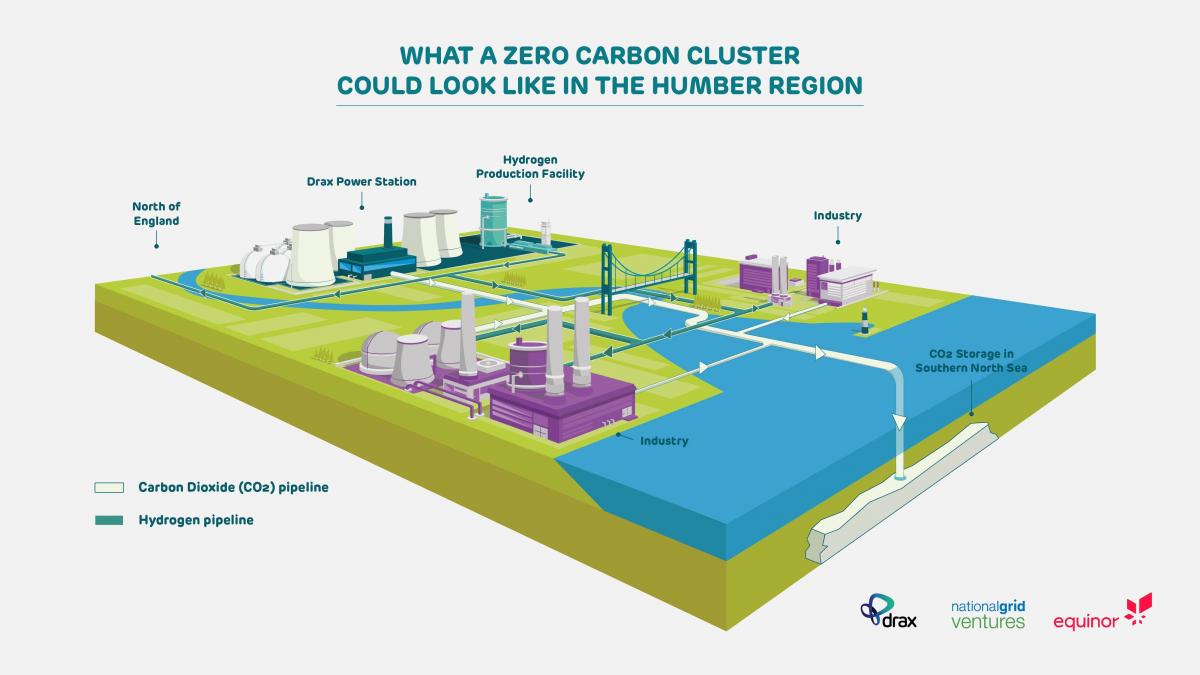

It’s fast-tracking bids from two industrial clusters, which aim to capture and store carbon dioxide from industry, power, and hydrogen production by the mid-2020s. Value for money decisions have yet to be made, but Hynet, in the north-west of England, and the east cluster centred on Teesside and the Humber could get a share of £1bn public funds.

Scottish ministers decried the decision to leave the north-east’s long standing Acorn project in reserve. It’s designed to decarbonise sites such as Ineos’ petrochemicals plant at Grangemouth and ExxonMobil’s ethylene plant.

England’s east cluster is responsible for half of the UK’s industrial emissions and involves BP, Drax, Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies. Drax is the anchor project for the Humber region, piloting bioenergy with CCS. Government wants to see 5m tonnes of greenhouse gas removals by 2030, through technologies including direct air capture.

The net-zero strategy recognises the skills reform needed across all sectors. “We need to make some fairly substantial changes to curricula in further education and higher education,” says Aldersgate’s Musat. . (See also ‘We won't turn Britain’s aging housing stock green without investing in the skills agenda’)

“On top of the supply of skills, there's also a question about demand for skills, because there are businesses which are really progressive ….. but there are others who are still on the fence: do we go for business as usual? Or do we embrace the transition now? If this net-zero strategy provides that long-term clarity on where we're headed, hopefully that's going to boost the demand for low-carbon skills amongst employers and create a virtuous circle.”

Currently, the UK runs the risk of creating two visions of Britain. Climate transition cannot be restricted to the better off

There was also widespread concern that the government’s strategy to address heating of buildings, which account for 25% of UK emissions, could be derailed by lack of take-up of technologies like heat pumps.

While grants of £5,000 will be available to homeowners from next year to replace gas boilers with electric heat pumps, only £450m has been allocated over the next three years, enough to supply 90,000 households, and there are concerns that the grants won’t fully compensate for higher installation and running costs.

Financial services provider Legal & General put the funding gap for the average UK household at nearly £15,000 for a ground source heat pump and £4,000 for solar panels.

“Currently, the UK runs the risk of creating two visions of Britain: one where more affluent communities benefit from the green and clean technologies of the 21st century, and another where less affluent communities do not. Climate transition cannot be restricted to the better off,” Legal & General CEO Nigel Wilson said.

Aldersgate Croup sustainable heat CCS HyNet green skills SAF