Hydrogen seen as having limited applications for transport

Hydrogen-powered cars, trucks, ships, or airplanes are unlikely to become a major part of the transition to a low-emission economy, with direct electrification cheaper and more efficient for most transportation, reports say.

Related Articles

The economic logic behind hydrogen as a fuel for certain modes of transportation, especially light vehicles, buses, most long-haul trucks, trains, and aviation, has been called into question by recent studies from oil majors, consultants, and environmental non-government organizations (NGOs).

Hydrogen may still arise as a preferred fuel for some small aircraft and heavy trucks, and for maritime shipping, the studies say.

Low-emission hydrogen has been touted as a potential replacement for petrol and diesel in most forms of transport, with hydrogen fueling stations imagined alongside charging stations and petrol pumps in service station forecourts.

But the immaturity of the technology and the necessary infrastructure means hydrogen as an everyday fuel may take time to establish itself.

“I think it's slowly sinking in that hydrogen is not a quick fix or silver bullet and that there won't be abundant quantities available,” says Geert Decock, Electricity and Energy Manager at the European Federation for Transport and Environment (T&E).

“The idea that we ship this hydrogen fuel from all over the globe into Europe will create new dependencies that maybe we don't want. Getting off oil and importing hydrogen from Saudi Arabia. Is that clever policy?”

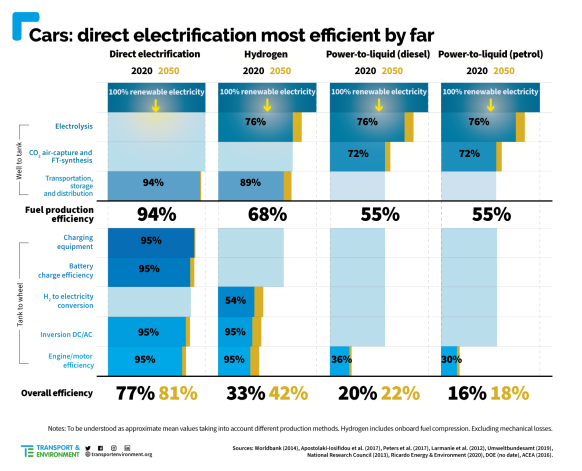

Cars: Direct Electrification Most Efficient by Far

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Transport & Environment

Hydrogen trucks

Hydrogen-powered fuel cell trucks are also being tested for long-haul trips, where an equivalent battery may be too heavy, but a lack of infrastructure, a lack of available clean hydrogen, low efficiency, and high costs, have prompted some to claim that, even in this sector, the gas is a far from a perfect solution.

Even the trucking industry seems unsure as to the potential for hydrogen technology.

In 2021, Volkswagen-owned, heavy-duty-truck manufacturer Scania dismissed the technology as inefficient and expensive, but then in 2022, the Swedish company said it would join with U.S. electrolyzer manufacturer to build 20 hydrogen-powered trucks as part of the HyTrucks project.

The HyTrucks project aims to put a 1,000 trucks on the roads in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany by 2025.

“For trucks, we think that 0.1% of the share will be fuel-cell powered, only for very niche applications. We think, once you start adding up cars, vans, and trucks, the whole road transport sector in our view will go battery electric,” says T&E’s Decock.

T&E, which acts out of Brussels as an umbrella organization for NGOs working to decarbonize the European transport sector, sees Fuel Cell Electric Trucks (FCET) accounting for only 0.1% of long-haul sales and 0.02% of total freight sales throughout the 2030s.

FCETs only beat diesel in a few use cases where a company needs the flexibility to sometimes drive short distances and other times extremely long distances, T&E said.

Zero-emission uptake potential (through battery electric trucks, or BETs) for all urban, regional delivery, and long-haul trucks, will reach 99.6% in 2030 and 99.8% by 2035, according to a T&E brief on an independent research report commissioned by T&E and Agora Verkehrswende and conducted by Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO).

“The main argument against FCEV for T&E remains the inefficiency of the electrolysis process and the resulting higher costs. As long as green hydrogen remains a scarce resource, it should go to those applications where direct electrification is not feasible,” the study found.

Multinational oil and gas company BP, in a recent addition to its Energy Outlook 2023 ‘How Energy is Used’, found that, even in the most optimistic scenario of reaching net zero by 2050, hydrogen would be the preferred fuel for only just over a quarter of medium and heavy vehicles.

Under BP’s least optimistic scenario, in which the rate of decarbonization continues at its current pace, hydrogen would be the preferred fuel for less than 15% of such vehicles.

“The choice between electricity and hydrogen is finely balanced and depends on use case,” BP said, adding that electricity required large, expensive batteries and time-consuming charging, while hydrogen required costly fuel cell stacks and gaseous storage.

Light vehicles would be almost 90% electric and less than 5% hydrogen under the net zero scenario, it said.

Taking flight

Hydrogen use in aviation has also faced resistance, with the BP report noting that a combination of the slow turnover of the current liquid-fuel based fleet and the range requirements for longer haul flights mean electric and hydrogen-based solutions will play a very limited role in the decarbonization of the aviation sector.

Hydrogen may play a part in the creation of synthetic aviation fuels (SAFs), especially in BP’s most optimistic net zero scenario, where it saw hydrogen-derived synthetic fuels 1-2% of total jet fuel by 2030 and 10-30% by 2050.

Hydrogen and electric propulsion will reduce aviation emissions by less than 5% by 2050 due to the time required for both technologies to mature, according to a July report by global management consulting firm Bain & Company.

“The combination of developing the technology, testing the engine, and ultimately incorporating it on an aircraft that worked its way into the fleet takes time,” says partner at Bain Jim Harris.

“We see a world where you could have hydrogen aircraft available to the market in the early- to mid-2040s, but that would represent such a small portion of fleet uptake by 2050 it just doesn't contribute to the net zero target.”

The slow turnover of airlines’ fleets, where an aircraft typically has a 25-30-year lifecycle, and the long time many new technologies take to evolve and work their way through industries mean that for a real reduction on aviation emissions, prices must rise and demand needs to fall.

Bain & Co sees airlines efforts to decarbonize will increase operating costs by 8-18% by 2050 and significantly erode profit margins which will start to feed through to ticket prices by as soon as 2026.

That would lead to a likely 3.5% drop in forecast global demand by the end of the decade, it said.

“I think we're running a real risk on the current path we're on, which is to hit net zero by 2050, that we’ll see flying become a luxury good again,” says Harris, adding that this will have a direct impact on economic growth in a global market.

By Paul Day