Shipping looks to hydrogen-based fuels to decarbonize

Global shipping accounts for around 3% of all CO2 emissions and a drive to slash that has many in the industry looking toward hydrogen fuels to power the world’s fleets.

Related Articles

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) has called for sharp reductions in emissions from the ships which shift around 80% of trade around the world, with CO2 emissions to be cut, on average, by at least 40% by 2030 and 70% by 2050 compared to 2008 and total annual greenhouse gas emissions reduced by at least half by 2050.

The transition won't be cheap. Reducing the industry's greenhouse gas emmissions by 50% by 2050 will require an annual average investment of $40-60 billion over the next two decades, or around $1 trillion,m one study conducted by the University of Martime Advisory Services (UMAS) and the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) found.

Some developers are looking toward hydrogen as an alternative, with companies such as the luxury travel brand Explora Journeys and Kawasaki Heavy Industries manufacturing hydrogen-powered ships.

Hydrogen, however, is complicated to transport and store while ammonia, which is derived from hydrogen and nitrogen, is increasingly seen as a viable alternative fuel for the world shipping industry.

“There is a very big difference between the two fuels,” says Director of Research & Development and Engineering at the Finnish company Wärtsilä Juha Kytölä.

“Ammonia is extremely easy way to carry energy. Unloading and offloading hydrogen is much more challenging because ammonia is a lazy fuel, but hydrogen is a nervous fuel. It has the tendency to ignite for whatever reason.”

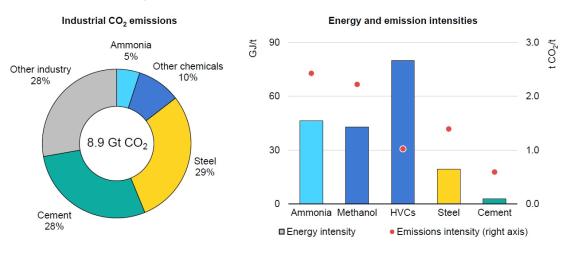

Energy consumption for and emissions from ammonia production in context, 2020

(Click to enlarge)

HVCs - High value chemicals, including ethylene, propylene, benzene, toluene, and mixed xylenes

Source: International Energy Agency, 2021

Building distribution networks

An ammonia fuel network for the maritime industry would also easier to create than one based on hydrogen.

“If you have to consider the logistics, it’s far easier with ammonia. There are big thoughts about Japan having the need for energy and Australia having a lot of sun, so Australia could create a lot of ammonia and bunker it with ships to Japan where they release the energy,” says Kytölä.

Wärtsilä has partnered with five other companies as part of the Zero Emission Energy Distribution at Sea (ZEEDS) initiative which aims to create an efficient infrastructure for distribution of zero-emission fuels.

Ammonia is also considerably easier to store compared to hydrogen, which needs to be cooled to -253C before it takes a liquid form.

“We’ve been transporting ammonia in the industry for a number of years. It’s not cryogenic and can be stored at -33C so requires less cooling than hydrogen,” Mark Darley, Marine and Offshore Director, Lloyd’s Register said during the Global Maritime Forum webcast ‘Ammonia as a shipping fuel’.

The Green Hydrogen Organization’s (GH2’s) “100 by 30” initiative, which is calling for the production of 100 million tons of clean hydrogen a year by 2030, sees a fifth of that dedicated to the production of some 100 million tons of green ammonia (around half global ammonia production today) to decarbonize 10% of global shipping.

However, for such an ambitious project, governments must price carbon emissions, set targets for using green hydrogen, use contract for difference, develop production tax credits and other incentives, and invest in infrastructure for renewable energy and transportation, such as measure recently adopted by the United States, says CEO of the GH2 Jonas Moberg.

The U.S.’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) measures announced in August are estimated to provide some $13 billion in value across the industry over the next ten years through a Clean Hydrogen Production Tax Credit (H2PTC) with credit based on a sliding scale depending on the levels of carbon emitted during production.

While the IRA aims to incentivize clean, or low-carbon, hydrogen, targeting life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from well-to-wheel, the Infrastructure, Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA) is centered on boosting production through the creation of vital infrastructure.

“What the United States is doing with the IRA is truly game changing. It is redirecting investment flows from the rest of the world to the United States. It really is catalyzing, and in a sense addressing a first mover disadvantage that a lot of companies have been worried about,” says Moberg.

Recent agreements at the COP27 binding developed nations to help fund decarbonization in less wealthy nations could mean international investment banks are reformed to “be fit for purposes to fund the transition,” Moberg says.

“To some extent, what needs to happen is that these banks need to make large scale renewable and green hydrogen production in developing countries and emerging economies competitive with the IRA,” he says.

Exploring derivatives

Ammonia as a fuel has its limitations, however, not least that it is an inefficient energy carrier losing almost 90% of input energy when used for power generation, according to business intelligence company CRU.

It is also unpleasant to be around.

“The most prevalent (problem) is that it’s a highly toxic, corrosive and flammable gas, it is slightly harder to ignite than other fuels. The main safety hazard to using ammonia is contact with skin or breath,” said Lloyd Register’s Darley.

Burning ammonia produces laughing gas, or nitrous oxide (N2O), which is a potent greenhouse gas, and research has been focusing on the exhaust emissions following combustion.

“It requires higher temperatures than we see today so that is part of the engine development and we look at it from a solutions point of view. How can we make a safe and efficient solution that does not emit strong greenhouse gases like N2O? Our idea is to control the combustion process to limit the emission,” Brian Østergaard Sørensen, Vice President, Head of Research & Development Two-Stroke, MAN Energy Solutions said during the ‘Ammonia as a shipping fuel’ webcast.

At the Danish shipping giant Maesk, the solution to ammonia’s downsides is to turn to another of hydrogen’s derivatives, methanol.

“We’ve already decided to go for methanol – from an operational, from a safety an environmental perspective, this is the preferred fuel,” Maesk’s Head of Decarbonisation Morten Bo Christiansen said during Maesk's recent ESG Investor Day.

“Engine technology is available and has proved out at sea and because it is a liquid it is relatively easy to handle, the infrastructure would be simple, and even if it does have a lower flashpoint compared to other marine fuels then there are some safety challenges, but they are manageable.”

The downside to methanol meanwhile is that, when it’s burned, it emits CO2, a problem Maesk researchers are working on solving, while on the plus side, the company sees methanol production scaling faster than ammonia.

“In order to scale this decade, green methanol is the only realistic pathway for us and we are quite happy to see that several of our peers have decided to go along this fuel pathway and have ordered a methanol power bases. The 1.5C scenario is balancing on a knife edge and we need action now,” Bo Christiansen said.

By Paul Day