Hydrogen heating plans receive lukewarm reception

Plans to use hydrogen as a domestic heating fuel face skepticism but proponents say hydrogen boilers can complement other low-emission solutions.

Related Articles

Almost half of global final energy consumption in buildings was to heat and cool spaces and heat water in 2020 and the vast majority of that was produced from fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Appliance manufacturers and utilities are studying to what extent replacing natural gas boilers with hydrogen boilers, alongside electricity-powered heat pumps and increased energy use efficiency, can help decarbonize temperature control in homes and office spaces.

Netherlands-based BDR Thermea Group develops and supplies products and services aimed at cutting carbon emissions from buildings, including heat pumps, and has been running pilots for its fully-hydrogen run boilers in the Netherlands, Britain, France, and Germany.

BDR Thermea’s 100% hydrogen boilers have run well during the trials, according to the company which by mid-November will begin its first large-scale application of hydrogen boilers in a real life setting in Lochem, the Netherlands, by installing the technology in 15 homes.

“The owners of these homes wanted to be part of the experiment to see what would be possible in terms of the energy transition because it’s close to their hearts. This will be the first hydrogen street in the world,” says BDR Thermea Group’s Communications Director Dennis Mikkelsen.

The company is using green hydrogen in its own R&D laboratory and at its first real-life pilot, but the Lochem pilot will use grey hydrogen in the beginning to focus on the application in the homes and distribution via the existing gas grid.

If demand exists, the company is ready to scale up, Mikkelsen says, adding that the use of heat pumps remains the best option for new homes while older homes that would need retrofitting for sole heat pump use are likely to benefit from the addition of a hydrogen boiler.

“At BDR Thermea we do see heat pumps as a no-brainer in new build setting and in well insulated homes. And then for existing houses we see that hybrids are playing an important role today and in the coming years,” he says.

Vested interests

In a review of 32 studies on the use of hydrogen for space and water heating carried out at international, regional, national, state, and city levels by a range of organizations, the technology did not fare well against alternative options such as heat pumps, solar thermal, and district heating.

The review, ‘Is heating homes with hydrogen all but a pipe dream?’ by principal and director of European programs at the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP), Jan Rosenow, found that the widespread use of hydrogen for heating was not supported by any of the 32 studies and was, in fact, less efficient, more resource intensive, and associated with larger environmental impacts.

The studies reviewed were carried out by organizations including universities, research institutes, intergovernmental organizations, and consulting firms while industry-funded studies were excluded to avoid potential bias.

“The owners of the gas networks, especially the gas distribution network, have a vested interest in the continuation of using gas for heating because you’re basically providing them with a guarantee that they can use their assets in perpetuity,” says Rosenow.

“The manufacturers of heating systems that make predominantly combustion systems that run fossil fuels have an interest in the continuation of having gas, whether that’s natural gas or hydrogen or something else. That’s where most of the interest is coming from, from the industry itself.”

The suggestion that it was possible to replace the gas and leave everything else in place – a one-to-one swap that appliance manufacturers such as BDR Thermea Group agree is not viable – is very attractive but deeply flawed, says Rosenow.

“Hydrogen is a much smaller molecule, and it can leak easily, there’s issues around embrittlement, and you have to make sure that all of the pipework from the transmission distribution grid to the internal pipework in homes is fit to have hydrogen in it, and we don’t know the extent that is the case. There will be a lot of upgrades needed, especially in older buildings, so it’s not so simple,” he says.

There’s also the issue of pollutants. Burning hydrogen in air produces mostly water but also nitrogen oxide (NOx) which could become an important source of local air contamination.

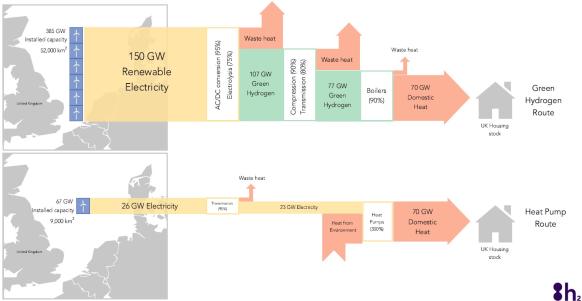

Heating the UK with Heat Pumps or Green Hydrogen

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Hydrogen Science Coalition

Relative inefficiency

Assuming hydrogen produced from electrolysis, which is about 75% efficient, is used in a boiler of 90% efficiency, the overall efficiency of electricity to heat is about 68%.

However, a heat pump with an efficiency or COP (coefficient of performance, a measurement of the efficiency for heat pumps) of 300% would be four times as efficient converting electricity to heat as electrolytic hydrogen, says project researcher at University College London Mark Barrett.

Professor of Energy and Environmental System Modelling, Barrett notes in his paper ‘Heating with steam methane reformed hydrogen – a survey of the emissions, security and cost implications of heating with hydrogen produced from natural gas’ that, assuming an average heat load of 35GW, the average electricity supply required would be 14GW for heat pumps versus 60GW for electrolytic hydrogen.

Installing a heat pump can be expensive, especially since it would need to be coupled with full heat insulation of the home – potentially costly for older houses – compared to replacing a gas boiler, but the relative inefficiency of making green hydrogen, distributing it, then burning it for heat, means the end costs would be higher via the hydrogen route.

“You need four times as much electricity supply for heat delivered from green hydrogen as opposed to heat pumps and that means that upstream costs are hugely greater for green hydrogen than they are for heat pumps,” says Barrett.

Even considering the necessary reinforcement to the electricity distribution grid and the costs of installing heat pumps in every home, the cost of green hydrogen for the same result would be much higher, he says.

Meanwhile, heat pumps can also be reversible and can cool as well as heat, which makes them useful in all seasons, especially as heat waves become more common.

“My own view on hydrogen is that the main use is in industry, such as for iron and ammonia production, and for some processes such as glass making when you need high temperature flames,” he says.

As for residential heating, the extra power needed to produce the necessary hydrogen to feed boilers in every home would take decades to install, time that the energy transition can barely afford.

“If you need four times as much electricity per unit of heat then that’s an awful lot more generation,” he says.

By Paul Day