Sweden leads the charge in green steel projects

Swedish steel companies will ramp up the country’s steel production over the next few years as green hydrogen helps drive the transformation of one of the hardest industries to decarbonize.

Related Articles

Almost 90% of Sweden’s population of just over 10 million is squeezed into only 1.5% of the country’s land mass, while in the north there is abundant emissions-free power generation with hydroelectric power from plants along the massive Lule River (44% of total), a growing wind industry (13%), and nuclear power (41%).

“Sweden has an advantage going forward. They were the first to step up. They have access to electricity and hydropower. They have an industry which is linked to what (mining company) LKAB does there, so they have products in place which enables them to do this transition. And there is a mind-set in Scandinavia which is different from other places,” says Benedikt Zeumer, a partner at McKinsey and expert on metals and mining practice.

Non-carbon-emitting power forms a central part in Sweden’s goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 and, while the government is yet to draw up an official green hydrogen strategy, there are already several major industrial projects where hydrogen is central.

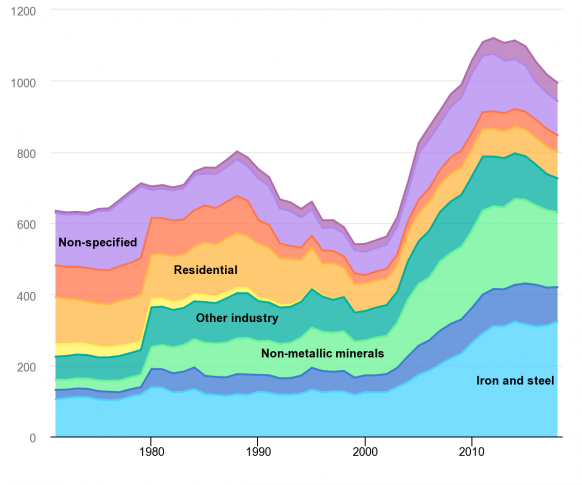

Coal total final consumption by sector, 1971-2018

(Source: International Energy Agency)

Twice the output

Steel is one of these industries and Swedish startup H2 Green Steel, founded in 2020, is building a full-integrated, digitalized, and automated steel plant it says will double the country’s steel output over the next 8 years.

“When we launched the venture, we thought that it would be for the automotive industry, both heavy trucks and light cars. But what we’ve seen is that there is a very big interest from construction,” says Head of Business Unit Hydrogen at H2 Green Steel Kajsa Ryttberg-Wallgren.

“The main reason for that is that you have this public procurement in certain countries now with a very high focus on decarbonizing the product and they are willing to pay a premium for a green steel product.”

H2 Green Steel aims to install electrolyzers as an integral part of the steel plant to produce the hydrogen needed to manufacture 2.5 million tons of high-quality steel a year in the first few years and 5 million tons by 2030.

That compares to Sweden’s entire steel production of 4.7 million tons in 2021, according to World Steel Organization figures.

The company’s first customers have agreed to pay a 25% premium on its green steel, says Ryttberg-Wallgren.

The greenfield steel plant in Boden will include giga-scale electrolysis, a reactor to refine iron ore to direct-reduced iron (DRI or sponge iron) using green hydrogen direct from the electrolyzer, and an electric arc furnace (EAF) to heat a combination of DRI and steel scrap to a homogeneous melt of liquid steel.

From the EAF liquid steel is turned into steel products in an integrated process called continuous casting and rolling which keeps the steel warm from the furnace to finished product, helping reduce energy consumption by 70% by skipping a process traditionally powered by natural gas, the company says.

Fossil-fuel-free value chain

Swedish steel manufacturer SSAB, miners LKAB, and state-held power company Vattenfall banded together in 2016 to create HYBRIT, which aims to create a fossil-fuel-free value chain from mine to steel using renewable electricity and hydrogen.

Operating in Sweden and Finland, SSAB says it is the largest carbon-emitting company in the region, churning out 10% and 7% of CO2 emissions of Sweden and Finland respectively.

It was this that drove the company to produce its first emission-free steel in 2021 during a trial campaign, steel that was taken up by Volvo for its first fossil-fuel-free vehicle, a load carrier for use in mining and quarrying.

In January this year, SSAB announced it would speed up its transition and remove, in principle, all CO2 emissions by around 2030, 15 years ahead of the previous plan.

“Even though SSAB has amongst the most CO2 efficient blast furnaces in the world, we are still a huge carbon dioxide producer, and at the same time, we are producing very high-end steel products for our manufacturing industry,” says SSAB CTO Martin Pei.

“For SSAB this was really the long-term business, sustainability issue. Before the Paris agreement was negotiated, SSAB realized that we needed to solve this issue from its root cause and in a way that we can build up a long-term sustainable business.”

Green hydrogen plays a key part of HYBRIT’s strategy, both for the iron ore reduction and to be stored for use during potential intermittency problems from wind-power electricity generation

“In the future, our plan is to construct large-scale hydrogen storage in order to accommodate wind power fluctuations, so when there is a lot of wind, we’ll produce more hydrogen and store it and when there is less wind, we can use hydrogen from the storage,” Pei says.

SSAB steel production using the hybrid technology, which at first will produce 1.3 million tons of steel from the new plant but will ramp that up significantly over the next few years, will need at least 10% of Sweden’s total electricity consumption.

Rising investment in wind farms in the north of the country means Pei is confident there will be sufficient electricity to support the company’s transition.

Deep underground

Like H2 Green Steel, the transition is reliant on the inclusion of the entire value chain and having LKAB, a 130-year-old mining company currently producing 80% of the European Union’s iron ore and 20% of Europe’s steel industry’s iron ore, form part of the HYBRIT project is essential.

LKAB is in its own transition from iron ore pellets to the more processed sponge iron.

“LKAB intends to invest between 1-2 billion euros ($1.1-2.2 billion) a year for 15-20 years scaling all this up to change, not only this first 1.3 million tons, but our entire production portfolio successfully from iron ore pellets into sponge iron. You do that with green hydrogen,” says Niklas Johansson Senior Vice President of the Communication and Climate Unit at LKAB.

Failure to transition away from fossil fuels in mining and heavy industries like steel require long-term planning and commitment across the industry’s value chain, Johansson says.

“In five or six years, if we haven’t managed as a country to make sure that we start using the technologies available for this transition, we’re going to be out of options,” he says.

“But it takes scale because, if we do it at scale, it’s going to be competitive. If we don't, it'll be little more than a trial run."

By Paul Day