Vogtle’s troubles bring US nuclear challenge into focus

Cost and schedule overruns have plagued the construction of two large advanced reactors at the Vogtle nuclear power station but, those in the industry say, lessons learned from the build will help guide the U.S.’s ambitious nuclear program going forward.

Related Articles

Plant Vogtle Unit 3 entered commercial operation at the end of July and marks the first U.S. deployment of Westinghouse's AP1000 Generation III+ reactors.

It is the first new nuclear reactor to begin operation in the United States since the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Watts Bar Unit 2, which connected to the grid in 2016. However, as a deferred unit on which construction began in the 1970s, Vogtle 3 and 4 are considered the first newly-constructed reactors since Watts Bar Unit 1 which started in 1996.

When Southern Company, via its electric subsidiary Georgia Power, brings Plant Vogtle Unit 4 online at the end of 2023 or beginning of 2024 the new units will collectively bring an additional generation capacity of 2.2 GW to the State of Georgia and are expected to run for 60-80 years.

The start of the reactors has been hailed as a major milestone in U.S. nuclear power construction, but the units arrived more than seven years later than originally planned and at a budget of more than double the preliminary projected cost at over $30 billion.

“Building new nuclear units is a complex process – and building the first new nuclear units in the U.S. in more than 30 years makes the process that much more complex. Though the road was challenging, it was one we had to travel, and we did it,” Southern Company CEO and President Chris Womack says in a written response to questions.

“This decade-plus journey, which involved developing a global supply chain, managing through a global pandemic, tens of thousands of American craft workers and engineers and millions of labor hours, combined with a group of committed co-owners and regulators that had the courage to support new nuclear power as an option when others didn't, proves that we can accomplish monumental things when we share a common vision.”

Lessons learned

Even just moving from Unit 3 to Unit 4, lessons have been learned and have been applied, says Womack.

“On Unit 3, Hot Functional Testing took 94 days to complete. For Unit 4, that same testing was successfully completed in 42 days,” Womack says.

The U.S. government in partnership with the private sector has identified a need for more than 200 GW of new nuclear capacity by 2050 as part of its plans to reduce harmful emissions from energy generation technology.

Projects such as Vogtle, considered first-of-a-kind (FOAK), have helped highlight what must and must not be done, says Jigar Shah, Director of the Loans Programs Office (LPO) at the Department of Energy (DOE).

Complete the design before the start of construction, build a strong contractor base, follow best-practices around mega-projects, make sure you have a large enough trained workforce, and assure the project has solid federal support, he says.

“I think that these are some of the lessons learned (from Vogtle) as we enter this next phase of the nuclear renaissance,” says Shah.

The DOE’s ‘Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Advanced Nuclear’ expands on the issues which hit the Vogtle plant and caused costs to skyrocket and schedules to slip.

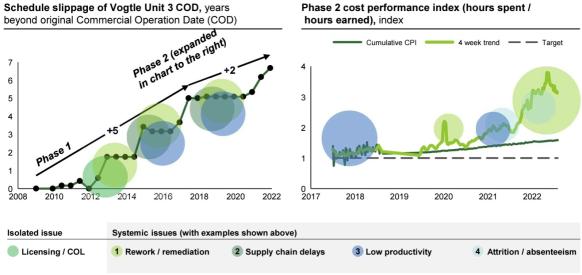

Schedule slippage and performance against cost performance index at Vogtle

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Georgia Public Services Commission

Rework was a significant source of project delay, with test failure rates of components between 40-80% over different time periods, meaning many tested components didn’t function properly and needed to be fixed.

There were supply chain delays, with modules arriving late, incomplete, or both, with some designs sent to manufactures changed after production began, some designs were unrealistic or there was a lack of quality-assurance paperwork which held up shipping.

Productivity was low due to “acute shortages in key trades” which necessitated the hiring of an inexperienced work force, resulting in poor management that delivered inadequate directions and improper scheduling, and ended in difficult-to-construct designs.

Finally, attrition and absenteeism played its own part in the delay, with the COVID-19 pandemic impacting all workstreams with as many as 2,800 positive cases reported in December 2021 alone.

Especially high attrition, or churn – there was a 50% attrition rate on electricians for the two units – meant learnings rates were often not carried forward as originally projected, the DOE noted.

Going forward

The experience gained from the construction of Vogtle Unit 3 and 4 will help pave the way for the roll out of both large-scale, gigawatt-sized advanced nuclear and small modular reactors (SMRs), says Senior Vice President of Policy Development and Public Affairs at the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) John Kotek.

“What experience has shown in the nuclear space is, if you can get to a sustained program of new construction, in a stable regulatory environment, you can move down the cost curve, and you can do so smartly,” Kotek says.

“I think with SMRs and advanced reactors, we have a really good chance of getting there.”

Fifteen years ago, wind and solar faced similar cost constraints, with electricity costs as much as 15 times more than the same technology is producing today, Kotek notes.

Federal tax credits and renewable portfolio standards at the state level helped provide a guaranteed market rate, with national and local governments effectively sharing early-mover risks, he says.

Massive government subsidy programs such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Civil Nuclear Credit Program will help build momentum.

“What we saw with renewables shows that when you do something over and over again, and you provide a real strong incentive to ensure that that happens, you can get to lower cost. And I expect to see that happen with nuclear over the next 15 years or so,” Kotek says.

By Paul Day