Public commitment will help kickstart new nuclear

Explicit governmental commitment to nuclear power will help rebuild supply chains, provide certainty for investors, and attract new talent, analysts say.

Related Articles

To meet greenhouse gas emission targets, global nuclear capacity needs to triple by 2050, according to the OECD’s Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA), a gargantuan task that must begin immediately to be successful.

However, deploying almost one terawatt of new nuclear power capacity in just under three decades will require rebuilding fuel supplies, strengthening engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) lines, and training thousands of nuclear engineers.

A firm and definitive commitment by world leaders will be needed to rebuild an industry that has been plagued by the fickle whims of changing governments and shifting public opinions for decades.

Such support will foster medium- and long-term planning by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), bring down risk premiums from financiers, and help fill the relevant courses at colleges and universities.

“Ensuring certainty is essential for suppliers to have the credible business case to invest in maintaining nuclear specific quality management systems and expanding their manufacturing facilities for the possible greater volumes of equipment needed towards the end of this decade,” says Nathan Paterson, the Senior Program Lead for Supply Chain at World Nuclear Association.

“More overt support is needed by governments … At a higher level, international agreements between governments and industry can help to provide certainty.”

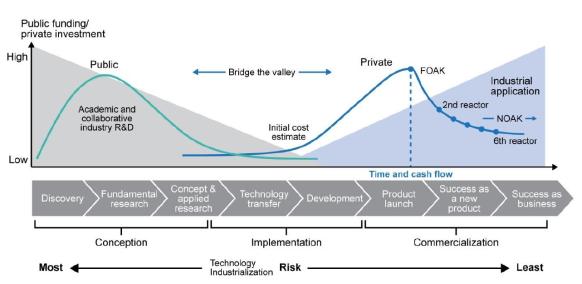

Bridging the valley

Private companies and financiers are often conservative in their support for untested designs and are reluctant to take the commercial risk until there is more certainty in a given market.

Governments can provide that certainty through committed strategies and public funding.

Industrialization of Innovation Bridging Public Funding to Commercialization

(Click to enlarge)

Source: World Nuclear Association 'The World Nuclear Supply Chain 2023 Edition'

“Governments need to truly reflect nuclear projects as strategic projects of national interest and develop ways in which they lessen the amount of taxation for nuclear equipment procurement,” says Paterson.

"In doing so, it presents one way to drive down some equipment procurement costs whilst possibly helping the supplier deliver at competitive price."

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – which offers production tax credits for existing reactors and tax incentives for advanced nuclear development – is one such ‘good practice’ he says.

Fuel, EPC, and workforce

The global supply chain has suffered over the last few decades with few new builds since the building bonanza of the sixties and seventies, and now recent geopolitical developments have taken an important supplier off the table.

Russia’s TENEX, part of Russian state-owned nuclear energy company Rosatom, is the only commercial supplier of uranium enriched to up to 20% and beyond the usual 5%, known as high assay, low enriched uranium, or HALEU.

Russian’s hold on nuclear fuel supplies, whether the fuel originates in Russia or passes through the country from an external supplier such as Kazakhstan, means the war with Ukraine will affect all sizes of reactors.

“Regardless of whether you want to build a large light water reactor or an advanced reactor, the security and reliability of the global nuclear fuel supply chain right now is in question,” says Ryan Norman, senior policy advisor for the climate and energy program at the Third Way energy think tank in Washington.

“The United States is doing a lot of work to make sure that we can catalyze private domestic enrichment and conversion capabilities, but that all takes funding. While people have their eye on the ball, it's not moving anywhere near as fast as it needs to.”

The size of the nuclear project will dictate which supply chain gaps will lead a project to stumble, Norman says.

Fuel supply issues would be the main concern for the construction and operation of one nuclear plant. Once you consider supply lines for as many as ten plants in the United States, U.S. EPC would be as big a worry, he says.

“When you want to build ten plants and they're $4 billion a piece, you can't throw all of that on to your balance sheet, and you really can't afford any delays or high interest,” Norman says.

"You need to make sure that your EPC is going to go off without a hitch and that’s a big bottleneck in the United States right now."

EPC delays and miscalculations during the construction of Vogtle Unit 3 and 4 lead to long delays and cost overruns, and prompted Westinghouse to file for bankruptcy in March 2017, according to an investigation by Reuters.

Tripling nuclear capacity over the next couple of decades, meanwhile, will involve the deployment of hundreds of new reactors worldwide, and that scale of construction will stretch another important element of the nuclear supply chain – that of the global nuclear workforce.

The strengths and weaknesses of today’s nuclear supply chain are only just beginning to emerge as ‘on paper’ projects start to look at what will be needed.

To significantly expand the sector, the key challenge for the nuclear sector is to overcome any limitations in the supply chain, but more analysis is needed to properly prepare for the job ahead, says World Nuclear Associaton’s Paterson.

“Governments in collaboration with industry should take serious steps to develop more accurate demand, capability, and capacity analysis of the supply chains for multiple projects going on in parallel (Long Term Operations, refurbishments and new build),” he says.

“In doing so the priorities of where focus and investment are needed to expand and ramp-up the supply chain can be agreed.”

By Paul Day