Growing findings of offshore cable damage hike pressure on protection

A number of offshore wind developers have followed Orsted and revealed cable faults, increasing the need for better protection as projects move further out to sea.

Related Articles

In April, leading offshore wind developer Orsted revealed an array cable fault that could affect up to 10 of its offshore wind farms in the UK and Continental Europe.

The cable protection system (CPS) used between turbine foundations and buried trenches was insufficiently stabilised, leading to abrasion and cable damage, Orsted said in its first-quarter results. The Danish group reported a warranty provision of 800 million crowns ($131.3 million) and said fixing the problem could cost 3 billion crowns in 2021-2023.

The CPS, tubes made of polymer, protect the cable from external factors such as sea topography and overbending. The cable is often stabilised by dumping a larger second pile of rocks over a scour protection layer, preventing abrasion from the initial scour protection and avoiding contact with boat anchors.

However, Orsted decided not to use a second layer of rock protection at its 573 MW Race Bank wind farm - installed off England's East Coast in 2018 - and other recently-commissioned assets. To rectify the issue, the operator will lay a second layer of rock to prevent further degradation and repair or replace any damaged cables, it said.

A number of other offshore wind operators have found cable protection faults, the companies told Reuters Events.

The impact of these issues differs between companies, but it highlights the need for improved practices across the offshore wind industry as operational learnings grow.

Wider issue

The omission of a second layer of rock protection seems to be a common source of CPS faults.

Swedish developer Vattenfall found damage to the CPS at its DanTysk offshore wind farm during regular maintenance in Spring 2020.

To rectify the issue, some cables will be replaced and the CPS system will be "upgraded according to best practice" that includes placing rock material around the CPS and cable systems, a Vattenfall spokesperson told Reuters Events.

"This work is ongoing and the cables are functional,” the spokesperson said.

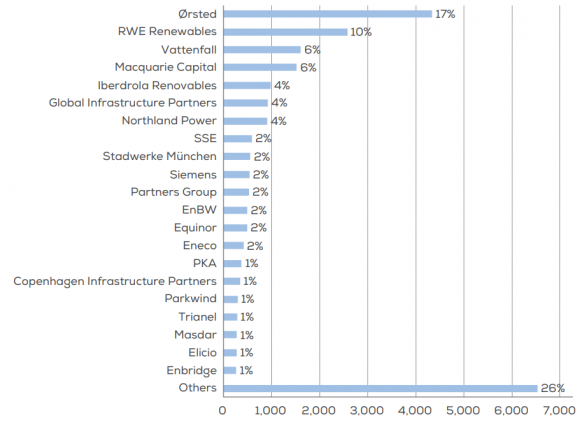

Owners' share of installed offshore wind in Europe

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: WindEurope

German group RWE has identified CPS issues at a "limited number" of recently-installed offshore wind assets, including the Galloper wind farm commissioned in 2018, the company said.

"We have identified and are taking steps to introduce remedial measures that will not have a material impact on RWE,” it said.

UK-based SSE Renewables has not seen any issues "of this nature," the company said. It is understood scour protection was not required at its 588 MW Beatrice Offshore Wind Farm, online since 2018, due to the nature of the seabed. Scour protection is believed to be in place at only 10 of 140 foundations at its older 504 MW Greater Gabbard wind farm and no issues have been identified during regular inspections.

Weak links

The reduction of CPS stabilisation measures in recent years may be due to a wider drive to cut costs. UK offshore wind auction prices fell by 30% between 2017 and 2019 and prices could fall further in the next auction due later this year. Soaring seabed lease prices this year have highlighted surging demand from an expanding group of developers.

However, cables remain a key source of offshore wind failures and are responsible for a large portion of insurance claims.

Cables represent up to 80% of construction claim payments but only 10 to 20% of capital spending, according to data from GCube, a renewables insurance supplier. During operations, cable losses represent 75% of claim payments.

“We expect to see a shift in losses from construction to operational as the industry matures,” Andries Veldstra, a senior underwriter at GCube, said.

Between 2015 and 2021 cable claims averaged 6.2 million pounds per loss, data from GCube shows. Claims for inter-array cables cost an average 4.3 million pounds. Issues include overbending and damage during installation such as jack-up legs being placed on top.

“The industry, under pressure to improve yields, efficiency and grow, needs to keep investing," Veldstra said. "We are seeing too many losses and insurance cover could be drawn back if action, such as more stabilisation systems, is not taken.”

Future cables

For newer projects, developers are selecting higher voltage cables to minimise the length of cable required and cut the cost of supply and installation. Offshore wind development is moving further offshore, putting greater pressure on cable reliability and cost.

Inter-array cables energised in 2020, by supplier

Source: WindEurope

A growing focus on cable management should incentivise better protection systems, Alex Neumann, Head of High Voltage at the UK's Offshore Renewable Catapult (ORE) research centre, said.

"This could mean making the CPS transition from buried happen tens of metres away from the turbine to avoid the turbulent base,” he said. “There will also be remote sensor technologies such as thermal condition monitoring to flag up cable failures before they happen.”

Engineering group Balmoral has introduced a CPS and stability management system which "avoids the costly secondary options of rock dumping,” Aneel Gill, Balmoral’s Product R&D Manager, said.

Learnings from Orsted and other developers should help produce cable solutions more tailored to offshore wind applications.

“We need information, including failures, to improve efficiency and reliability," Gill said. "Oil and gas developers share failure modes, but it is lacking in renewables.”

To accelerate new solutions, ORE is compiling anonymous operator data on subsea cable failures.

“We will use it as a benchmark against other industries,” Neumann said. “We are entering a new phase in offshore as wind farms age. The Orsted issue will not be the last.”

Reporting by David Craik

Editing by Robin Sayles