European pipeline strategy must play to hydrogen's strengths

A hydrogen pipeline network will likely play a key role in Europe’s energy transition but must be laid in accordance with hydrogen’s strengths rather than strive to be a one-for-one replacement of natural gas, say experts.

Related Articles

Hydrogen transportation is complicated, with huge amounts of potential energy lost when recovered from liquified gas, ammonia, or liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs), and many European countries will need to import the gas as they lack the renewable resources necessary for domestic production.

Transport and storage of hydrogen are essential puzzles to solve when considering a hydrogen economy, with off-takers often found in heavily industrialized and densely populated areas and production opportunities mostly located in remote, renewable-rich areas.

In January, German utility RWE announced it had joined forces with Norway’s Equinor to study the development of a hydrogen pipeline between the two countries, while in southern Europe H2MED is a proposed undersea pipeline between Barcelona in Spain and Marseille in France.

Under the 2050, 1.5C Scenario, around 55% of internationally traded hydrogen will likely be moved by pipeline and the remaining 45% will be shipped predominantly as ammonia, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Before large scale pipeline laying begins it should be decided where those pipelines go and which industries they will feed, says Research Fellow on Climate and Energy at think tank IDDRI Ines Bouacida.

“Hydrogen is not meant to be a new fossil fuel that is cheap and can be transported over long distances. It is going to be used only for some segments,” says Bouacida.

“Hydrogen is just not natural gas. We need to keep repeating that. The network in the long term is not going to be as big and it’s not going to play the same role.”

Import strategy

Many countries in Europe are going to struggle to find sufficient renewable resources at home to power greater electrification and decarbonize their current hydrogen demand.

In Germany, annual demand for hydrogen stands at around 1.7 million tons, or 22% of the European total. Turning that green will require a robust import strategy.

“Germany is the largest consumer of hydrogen in the European Union, and it wants to use renewable energy to decarbonize its current electricity demand. That demand will increase if it wants to decarbonize heating with heat pumps and mobility with electric vehicles,” says Alejandro Nuñez-Jimenez, Senior Researcher at ETH Zurich.

“Add to that an increased demand (of electricity to make) hydrogen and the numbers are telling us it will be very hard, or impossible, to meet all that with domestic renewable resources.”

Side by side

Building a hydrogen network will not be cheap and, for some high-use cases such as the steel industry in Sweden, it makes more sense to build the electrolyzers on site to directly feed the processes for which it is being made.

However, this is not always convenient or possible.

“In some cases, it might be easier to move the industry to where you can produce the hydrogen, but I don’t think this is a very appealing prospect for European policymakers,” says Nuñez-Jimenez.

“The key advantage of a pipeline is the cost compared to shipping, which is tremendous. So, from an economic perspective, (pipelines) would be very advantageous.”

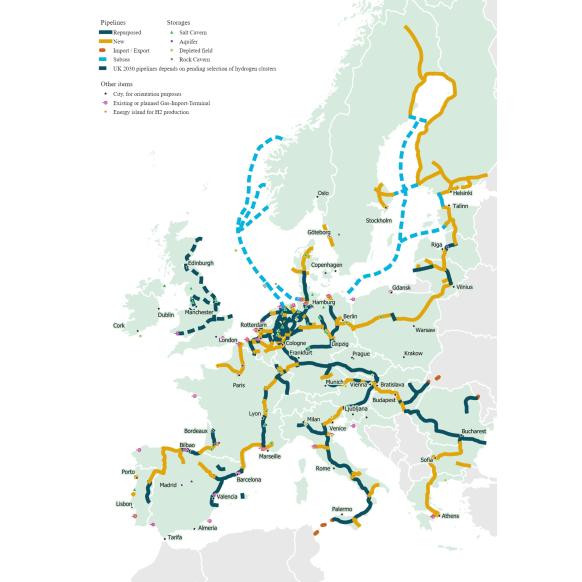

European Hydrogen Backbone Map

(Click to enlarge)

Source: European Hydrogen Backbone. ehb.eu

The European Hydrogen Backbone (EHB) initiative, founded in 2020, has published detailed, interactive maps of a potential pan-European hydrogen transport infrastructure and claims that, through an estimated total investment of 80-143 billion euros ($86 - $153 billion) for subsea pipelines and interconnectors linking countries to offshore energy hubs and potential export regions, transportation can be cost effective.

Transporting hydrogen over 1,000 km along the proposed onshore backbone would on average cost 0.11-0.21 per kilogram of hydrogen, the EHB says in its study ‘A European hydrogen Infrastructure Vision Covering 28 Countries.’

When hydrogen is transported exclusively via subsea pipelines, the cost would be 0.17-0.32 euro/kg per 1,000 km, it says.

Lock-in risk

While pipelines may be the most economical way to transport hydrogen, the initial laying of the infrastructure is an expensive and long-term effort that requires a long-term commitment, a tricky proposition when, today, the gas represents only 2% of the EU’s energy mix.

Repurposing existing gas pipelines requires a coordinated effort to decrease natural gas use at a similar rate to increased hydrogen use and the two gases have very different properties, including the need for more than three times the volume of hydrogen as natural gas to produce the same amount of energy.

These complications mean some worry that plans to invest first in blue hydrogen, produced from natural gas alongside carbon sequestration and storage (CSS), could mean later plans to pivot to renewable hydrogen are left by the wayside.

“The risk is that we invest in blue hydrogen technology and then you need to keep it on much longer than you had planned in the beginning. There’s a serious risk of lock in,” says IDDRI’s Bouacida.

Hydrogen is already widely used in heavy industries such as steel production and chemicals and the focus should be on decarbonizing those sectors with green hydrogen rather than building a pipeline infrastructure aimed at transporting hydrogen to every part of the economy, when very small amounts will likely be used for electricity generation or heating.

Getting started

The war in the Ukraine, and the consequent squeeze on gas supplies has left countries such as Germany scrambling for an alternative and hydrogen, to some extent, promises a solution.

“In the short, short term, whether the technology is available or not, or the volumes are available or not, Germany is being pragmatic and is starting a corridor. It wants this option in the future to import something greener, but are starting with what they have,” says Leslie Palti-Guzman, CEO of Gas Vista, a market intelligence and data analytics firm.

“I think it’s one option amongst others that they are considering, and they don’t have the luxury to bypass this. They need all the above right now.”

However, it will be important to decipher where the utilization of hydrogen is best, where it makes sense to direct a dedicated hydrogen pipeline, and where alternative sources of energy should be considered, says Palti-Guzman.

“What is going to be the main utilization? I think that is the question that has not been answered yet,” she says.

By Paul Day