Growing support for nuclear will help drive industry in 2024

A new-found momentum in support for nuclear power will help drive industry expansion and address shortfalls in 2024, say international nuclear agencies.

Related Articles

The COP28 environmental conference at the end of last year saw unprecedented support for nuclear power and concluded with a pledge by more than 20 countries and over 120 companies to triple the power generated by the technology by 2050.

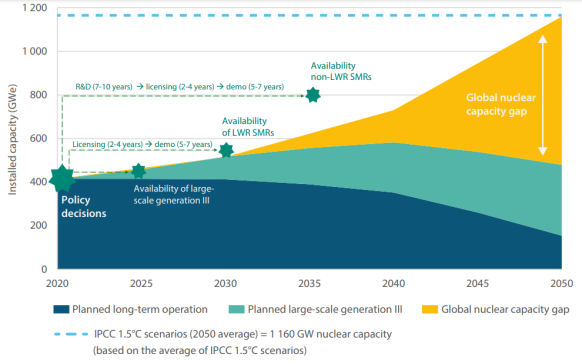

Raising capacity to 1.2 TW from the almost 400 GW generated today is seen as ambitious but necessary to reach net zero in studies by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) and the World Nuclear Association.

The goal would require a global buildout of new nuclear power stations at a pace not seen in Western countries since the 1970s.

“I think the biggest priority going forward is to work with the countries that have come around to the realization that they're going to need new nuclear,” says Director-General of the NEA William D. Magwood, IV.

“That is very much a non-trivial undertaking, because it's been quite some time since many countries have even considered the possibility of building new nuclear plants, so they don't have the infrastructure, the people, the industrial base or the supply chain.”

For Magwood, the COP28’s ‘Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy’ was an affirmation of progress that was already being made in the industry.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, many countries that had been dependent on Russian fossil fuels, especially in Europe, were left scrambling for an alternative power source and nuclear was the natural fit.

Those signing the declaration included countries that already had nuclear power, including Britain, the United States, Canada, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, Ukraine, Armenia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Czech Republic, Japan, Republic of Korea, Finland, United Arab Emirates, and France, alongside countries that were eager to start their own programs, including, Croatia, Moldova, Morocco, Netherlands, Poland, Ghana, Mongolia and Jaimaica.

Global installed nuclear capacity gap (2020-2050)

(Click to Enlarge)

Source: NEA

Taking stock

Building on the growing support will be key.

“The inclusion of nuclear energy in the COP28 Global Stocktake, which called for its accelerated deployment to help achieve deep decarbonization … were major milestones that we must now build on,” says Wei Huang, Director of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA’s) Division of Planning, Information and Knowledge Management, and coordinator of the IAEA’s COP activities.

However, both the IAEA and the NEA are profoundly aware of the challenges that lay ahead, not least how it’s all going to be paid for.

“To achieve these ambitious objectives, new ways to unlock investments, including public and private capital, are needed to help finance the historic scaling up that the international community is calling for, whether for nuclear newcomer countries, expanding nuclear countries or end users such as heavy industry and tech companies that need to decarbonize their operations with clean and reliable heat, steam, and electricity,” says Wei Huang.

Magwood agrees that financing will be one of the main challenges going forward.

He hopes ways to mitigating the effects of high interest rates and investor reluctance to offer resources at reasonable rates to the industry will be addressed at the NEA’s second ‘Roadmaps to New Nuclear’ confenerence to be held in September.

“We’ll be trying to bring some solutions to the financing question, which everybody worries about, as well as supply chains, and human capacity. I think those are going to be the three issues that we'll be focusing most on and countries are in the mood to really try to solve them,” says Magwood.

Political polarization

General elections around the world in 2024 offer their own challenges to expanding an industry that requires years of political support far beyond that offered in a four-year electoral cycle.

Deep polarization in the United States has paralyzed the legislative branch on many issues, freezing resource flows to much needed projects, including those in the massive Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

At the time of writing, U.S. Congress leaders had reached a deal over 2024 spending, though a divided House of Representatives and Senate must still approve the numbers.

Nuclear power, however, occupies a unique place when it comes to political differences.

On the left, nuclear power offers a clean solution to rising pollution and climate change, while on the right, nuclear power is a welcome replacement for aging coal-fired plants and a smart way to power industrial growth.

“I take some comfort in the fact that if you look back over the last 10-plus years, you'll see a remarkable degree of commonality in terms of Republican and Democratic policy priorities as they relate to nuclear power,” says Senior Vice President of Policy Development and Public Affairs at the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) John Kotek.

Regardless of the party in power, over the last three administrations large appropriations have been passed for nuclear research and development and the U.S. nuclear industrial reach has been extended across the world.

Vital R&D efforts, such as the Advanced Reactors Demonstration Program (ARDP), the Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-E), the Civil Nuclear Credit Program, and the lifting of a ban on investment in nuclear projects by the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), have all been passed by politicians on both sides of the divide.

“Nuclear energy is one of those rare areas of agreement between our political parties when it comes to matters of national importance,” says Kotek.

By Paul Day