Europeans push hydrogen in bid for energy independence

Europe is ramping up its green hydrogen ambitions as industrialized western economies scramble for independence from Russian oil and gas.

Related Articles

Fossil fuel prices have been on a steady rise since Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine February 24 and, with the EU counting on Russia for 45% of its gas imports and almost 40% of its total gas consumption in 2021, the drive for energy independence has intensified the focus on potentially home-grown sources such as hydrogen.

“Previously, talk about hydrogen was driven by carbon neutrality targets, especially after the pandemic. But right now, with what’s happening in Europe, the conversation has also extended to energy security. Moving to green hydrogen brings real benefits because the feedstock price is independent of borders,” says Head of Hydrogen Research for Rystad Energy Minh Khoi Le.

The costs of blue and grey hydrogen (from natural gas and carbon capture and storage, and from steam reforming, respectively) have risen to about $12/kg from $8/kg since the start of the war in Ukraine, according to Rystad Energy.

That price rise has made the economics of green hydrogen increasingly attractive, with calculated production costs of $4/kg in the Iberian Peninsula based on the lowest price of electricity at the latest solar auction..

“The decade ahead is a make or break one for the green hydrogen sector – if production can be increased as planned to more than 10 million tons (MT) globally by 2030 and costs cut to $1.5/kg or less, then the industry will become a permanent fixture of the global energy mix,” the study said.

Europe may still need to import some energy, even in a fossil fuel-free world, but the potentially large number of hydrogen producers, rather than just a handful of sources for fossil fuels such as oil and gas, will help spread the risk, Minh Le says.

“There would still be dependency on non-European countries’ production, but instead of getting 40% of your gas from Russia, you’ll be able to get it from North Africa, or the Middle East, or North and South America; even as far as Australia if costs get down low enough,” he says.

“Wind and solar power are still resource dependent, but there will be a lot more producers than just a select few oil and gas producers we have in the world today.”

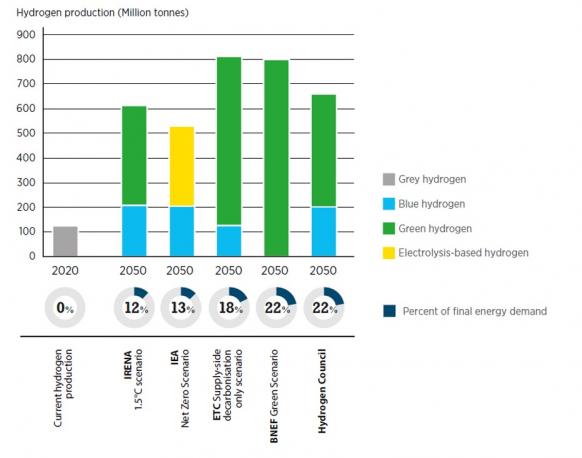

Estimates for global hydrogen demand in 2050

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

Hydrogen Accelerator

Following the invasion, the European Commission proposed an outline of a plan to increase the economic bloc’s independence from Russian fossil fuels “well before 2030”, REPowerEU, including a plan to boost hydrogen production.

The ‘Hydrogen Accelerator’ proposes an additional 15 MT of renewable hydrogen on top of the 5.6 MT foreseen under the ongoing ‘Fit for 55’ plan, to replace 25-50 billion cubic meters per year of imported Russian gas by 2030.

“This would be made of additional 10 MT of imported hydrogen from diverse sources and an additional 5 MT of hydrogen produced in Europe, going beyond the targets of the EU’s hydrogen strategy and maximizing the domestic production of hydrogen. Other forms of fossil-free hydrogen, notably nuclear-based, also play a role in substituting natural gas,” it said.

The EU stands ready to create a Task Force on common gas purchases at EU level, it said, which would help prepare the ground for energy partnerships in the Mediterranean region, in Africa, and the Middle East and the United States and it would be inspired the experience from the COVID-19 pandemic where member states coordinated to ensure an effective response.

Stranded in blue

Until the war, blue hydrogen – where hydrogen is taken from natural gas and the resulting carbon is stored – was considered an acceptable transition fuel for creating a hydrogen driven economy, but the direct line to green hydrogen is now more important than ever, says Secretary General of Eurelectric Kristian Ruby.

“The whole mood about blue hydrogen has changed significantly because it’s based on natural gas and Europe doesn’t have a lot of that, so the idea of importing gas and then stripping it of its carbon is becoming controversial,” he says.

Even before the invasion, the blue hydrogen route was under question.

“The expected cost reduction in green hydrogen coupled with stricter climate mitigation policies means that investments in supply chains based on fossil fuels (blue or grey) – especially assets expected to be in operation for many years – may end up stranded,” the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) said in its report ‘Geopolitics of the Energy Transition: The Hydrogen Factor.’

The European Commission’s plan is wide ranging and massive in scale, but there is concern that the 27-country economic bloc is too politically cumbersome and weighed down in Brussels bureaucracy to be effective when dealing with emergencies like the fallout from the war and the energy transition.

However, Ruby believes that European leaders are aligned over what needs to be done and that much of what has been laid out in the REPowerEU plan will be brought into law.

“Europe is the story of the hare and the tortoise. The EU policy machine is churning slower, but it’s getting there. It’s going to take a bit of time, but I think we’re going to see 80% of what’s on the table today becoming a reality,” he says.

By Paul Day