NRC fees stifle innovation, say operators, analysts

The user fee model employed by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is stifling innovation in the sector, creating a potential bottleneck for the regulator and must be changed to encourage a new wave of nuclear power, analysts and operators say.

Related Articles

The NRC’s near $1 billion budget each year is mostly paid for by annual fees charged to operators for existing, running nuclear reactors, but a large part comes from hourly fees charged to new license applicants, among others, and it is these costs that weigh on the NRC’s resources, flexibility and efficiency while imposing barriers to new entrants, according to a new report.

“The current fee model limits NRC’s capabilities to review advanced reactors, slows innovation, and makes the United States a less attractive regulatory environment,” the think tank Nuclear Innovation Alliance (NIA) said in a new report 'Unlocking Advanced Nuclear Innovation: The Role of Fee Reform and Public Investment.'

The fee model constrains the NRC’s ability to conduct broad, important rulemakings, licensing reviews and proactive research to support risk-informed, performance-based regulation, it says, adding that while fees charged to license applicants before they even start generating revenues is a burden on for developers with limited capital, small towns, rural communities, and industrial users.

Addressing the balance

The total NRC budget for this year is $844.4 million, down $11.2 million from the last year, according to a NRC statement on amendments to annual fees for full-year 2021 which followed the proposed fee rule published in February in the Federal Register.

After accounting for exclusions from the fee-recovery requirement and net billing adjustments, the NRC must recover $708.8 million of that total, with $185.9 million to be taken from Part 170 – hourly fees and including new license applicants – and $522.9 million from Part 171 - annual fees and existing licensees.

The NIA report is focused on the fees charged to newcomers via Part 170, and the NRC notes that it is from this category that billing is expected to be down this year from 2020.

The Part 170 billing is expected to drop from last year due to plant closures of Indian Point Unit 3, which shut down in April, and the Duane Arnold, which closed in October 2020, the completion of the construction activities at Vogtle Electric Generating Plant, Unit 3, and the completion of the NuScale small modular reactor design, the NRC said in its Federal Register Notice.

Part 171 billing, meanwhile, is expected to increase.

The hourly fees for staff services are determined fairly and equitably, NRC spokesman Scott Burnell said in an emailed response to questions.

"When you view the Federal Register Notice, it includes a list of ‘excluded activities’ outside the fee process. ‘Advanced reactor regulatory infrastructure activities’ accounts for $17.7 million of the excluded activities. This is an example of the NRC working to ensure our processes are not an impediment to licensee or applicant efforts," Burnell says.

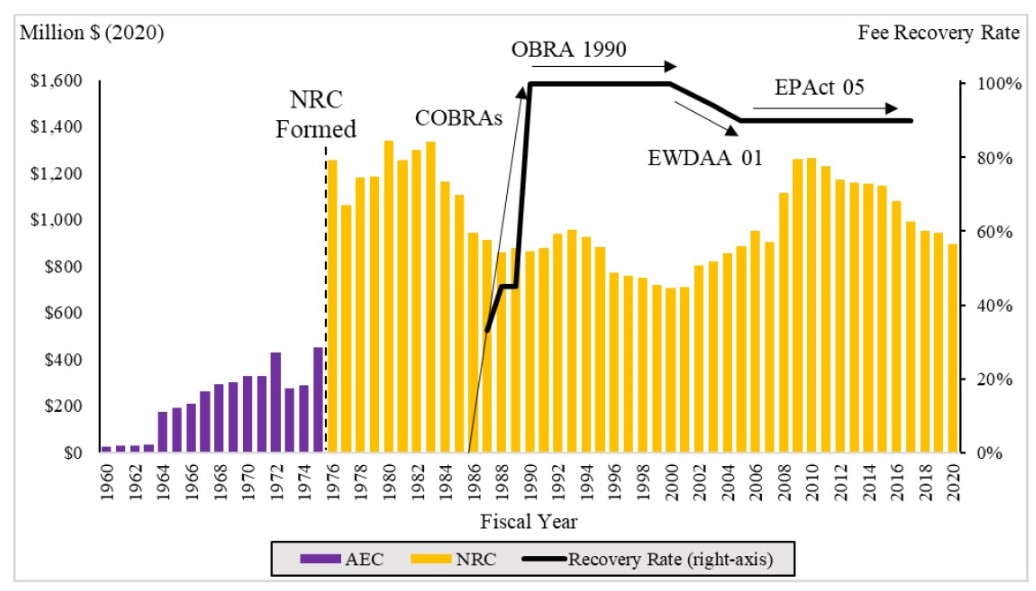

AEC and NRC Budgets vs Fee Recovery Rates, 1960-2020, 2020$

(Source: Nuclear Innovation Alliance, based on data from NRC and GOA)

NRC bottleneck

The NRC is required to charge fees to review a licensing application, currently standing at almost $300 per hour for staff time.

The depth and scale of the job of evaluating a new design means that these fees soon add up to be a sizable dent in a budding company’s finances.

The NRC’s review of NuScale’s Design Certification Application (DCA), its first-ever small modular reactor, was about 12,000 pages, including 14 topical reports and more than 2 million pages of supporting information, and took up over quarter of a million staff hours. The review cost the company around $70 million in fees alone.

The high entrance fee also weighs on the NRC's ability to do its job.

“While the financial burden on nuclear innovators can discourage innovation, the more pressing challenge of the cost recovery model may be that it limits NRC’s resources to address all the activities it needs to conduct in the next several years,” according to an opinion piece penned by former NRC commissioners Jeffrey S. Merrifield and Stephen Burns and executive director of the NIA Judi Greenwald.

The editorial points out that by 2027, the NRC expects that it could issue six or more operating licenses for advanced reactors and will be reviewing at least seven more license applications, making it difficult for the regulator to hire or train enough staff ahead of time.

“Without fee revenues from licensing applications, NRC cannot prepare to review those applications expeditiously. Without additional public investment, NRC cannot conduct enough of its own independent research and international engagement. This slows nuclear innovation and the adoption of advanced reactors to mitigate climate change,” it says.

Difficult first steps

Newcomers to the nuclear generation scene are feeling the pinch of moving their designs through the primary stages of the NRC’s evaluation.

“We’re two million dollars down the road with NRC fees, the formal application review hasn’t started and that will generate plenty of additional NRC invoices in the future. It’s important to know that this is for a demonstration platform that will not generate a dollar of revenue,” the Vice-President of Regulatory Affairs and Quality at Kairos Power Peter Hastings said during a webinar to present the NIA report.

Companies agree, however, that while the initial fees can be a huge impediment to newcomers, they help to weed out frivolous applications by a company looking for a cheap public relations win that would soak up the NRC’s time and resources.

“You can’t lower the cost to the point where people are submitting things for PR points in a disingenuous way with potential frivolous work. You should have skin in the game,” co-founder and Chief Operating Officer of Oklo Caroline Cochran said during the NIA webinar.

However, the discrepancies between the NRC and how other countries’ regulators raise funds puts the U.S. nuclear regulator on an uneven playing field, says Alex Gilbert, lead author of the NIA study.

Regulators in both the United Kingdom and Canada charge fees. However, their performance-based licensing system makes them more efficient and easier to navigate for non-light water reactor companies. In China and Russia, the state foots the bill.

The NRC fee system should be more like that adopted by other government agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, the Food and Drug Administration or the Federal Aviation Administration, says Gilbert.

“There are ways to do this that is fair to applicants but also respects agency resources and time,” he says.

“In the case of these hourly fees, you’re essentially charging for innovation, so if we’re trying to build a new generation of safer, more economic reactors that can really restore American competitiveness we’re kind of creating a regulatory barrier right now to that innovation.”

By Paul Day