New generation of reactors need next-gen licensing

The new generation of advanced nuclear reactors often differ from existing plants in size, technology, and safety features, and this requires updated licensing methodology, both domestically and internationally.

Related Articles

The world’s nuclear power regulators will be vital gatekeepers as technological breakthroughs and a widening scope of applications leads to the production of a spectrum of untested next-generation reactor designs.

Most existing nuclear plants have large, gigawatt-powered, light water reactors (LWR) and are built in a fixed location and used primarily to feed power into a national grid, granting regulators little experience licensing other technologies.

The new generation is more diverse and includes, amongst other things, reactors small enough to fit on a flat-bed truck and made to be moved frequently, high-temperature fluoride molten salt reactors, high temperature gas reactors, sodium fast reactors, small modular light water reactors, heat pipe reactors, and reactors with passive safety features.

This almost bewildering array of designs and state-of-the-art features has regulators such as the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) looking closely at how they’ve licensed nuclear power before and how it can bring those methods up to date.

“It’s going to be a whole menagerie of technologies, each one with its own technical challenges and technical expertise needed to address it,” says the Nuclear Innovation Alliance (NIA) Project Manager Patrick White.

Timing is a key part of the equation amid an increasingly complicated geopolitical backdrop and rising concerns over the effect of fossil fuels on the climate.

“We really want an efficient and effective regulator. A regulator that is doing its job but is also doing something in a timely way, because if we can’t ever build these reactor technologies because the licensing process is too slow, we can’t get the benefits of clean energy,” White says.

Flawed but fixable

In the spring of 2023, the NRC’s Commissioners will view the draft of a proposed new advanced reactor licensing framework (10 CFE Part 53), the creation of which has been described as a “once-in-generation” opportunity and what White calls “a flawed but fixable draft rule”.

“The issues in the NRC’s proposed approach are due, in part, to the challenges of preparing a novel rule subject to complex constraints in a short period of time and an imperfect approach to balancing regulatory predictability and flexibility in a new licensing rule,” White writes in the NIA brief ‘Bridging the Gap on 10 CFR Part 53’.

The draft comes after Congress charged the NRC, following direction from the 2019 Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act (NEIMA), to create a technology-inclusive, risk informed, performance-based regulatory framework for advanced reactors by 2027, though many stakeholders and policymakers requested this be completed by 2024.

After dozens of public meetings, hundreds of public comments, and thousands of pages of preliminary draft text, the proposed rule package has been received by some stakeholders as unworkable.

“It was a missed opportunity for the agency to come up with a streamlined process that would allow it to appropriately review these designs and determine if they met the reasonable assurance of adequate protection standard, but at the same time do it in a way that was not overly prescriptive,” says one source close to the NRC that asked not to be named.

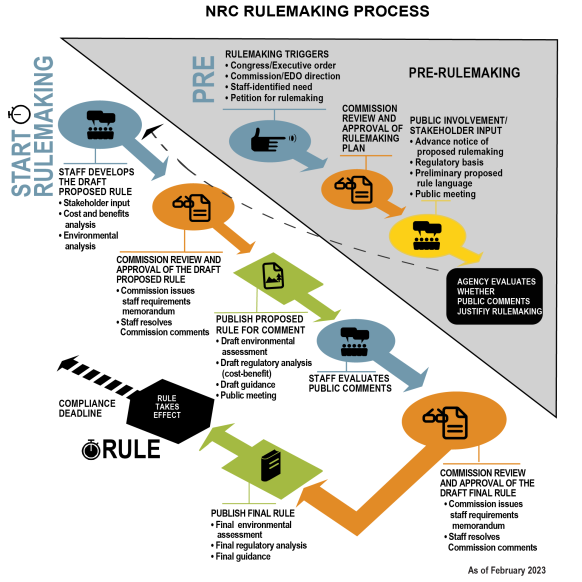

(Click to Enlarge)

Source: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC)

Around the world

While the NRC works on updating its own proposal, World Nuclear Association’s (WNA) working group CORDEL (Cooperation in Reactor Design Evaluation and Licensing) is promoting an environment where internationally standardized reactor designs can be widely deployed without major changes at the national level.

Such an environment would enable regulators to work together, or adopt the outputs from others, and see how designs could be acceptable within their respective frameworks without significant modifications, says CORDEL Program Lead Ronan Tanguy.

“This would improve nuclear power’s competitiveness and accelerate the deployment of nuclear plants around the world. Such a framework would maintain the sovereignty of national regulators but lessen the burden on them at a time when many new designs are being submitted for assessment,” says Tanguy.

National regulators are aware of the challenges in reviewing the more than 80 new designs currently listed by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) without international cooperation and, in some cases, have already started to reach across borders.

The NRC and Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) are working together on the GE-Hitachi small modular reactor (SMR) BWRX-300, and the French, Finnish, and Czech regulators are looking at EDF’s Pressurized Water SMR NUWARD.

The World Nuclear Association is working with policy makers, regulators, designers, vendors, and operators and international organizations to understand how to best learn from on-going regulatory activities, Tanguy says.

Such efforts support future design review activities and emerging countries, while complementing efforts such as the IAEA’s Nuclear Harmonization and Standardization Initiative (NHSI) to draw out best practices.

“Without a significant step change in collaboration between governments, nuclear regulators, and industry, the current trend of duplicating review efforts, turning what should be an efficient series of nth-of-a-kind projects into a never-ending series of first-of-a-kind projects, will continue,” he says.

By Paul Day