NRC, CNSC see eventual path to multi-lateral licensing

Close collaboration between nuclear regulators in the United States and Canada could, eventually, serve as a template for a more global, unified approach to nuclear power regulation, the heads of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) and the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) said.

Related Articles

“It’s important that we take small steps and iron out the wrinkles, and then open it up to others,” President and CEO of the CNSC Rumina Velshi said in a joint interview with Chairman of the U.S. NRC Christopher T. Hanson at the Canadian Nuclear Association (CNA) 2021 conference.

In August 2019, the NRC and CNSC signed a Memorandum of Cooperation (MoC) over licensing SMRs giving the agencies greater scope to lean on each other to share scientific information to support reviews of advanced reactor technology.

In August this year, the CNSC and the NRC completed their first collaborative project, issuing a joint report on feedback to X-energy in relation to its design for its Xe-100 small modular reactor (SMR).

The CNSC has also signed an Information Exchange Agreement (IEA) with Britain’s Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and cooperation accords with nuclear regulators in India, Japan, Switzerland and China.

While some have expressed concern that close contact between national regulators could compromise their sovereignty, Velshi said that, even between the United States and Canada, the final say goes to the local office.

“I’m hoping eventually we get to multilateral licensing, that ultimate step before licensing, that we have collaborated, have come up with harmonized requirements, harmonized reviews and that mature regulators like the NRC or CNSC or ONR have given their stamp on a particular technology,” said Velshi.

Such an approach would help foster much needed public trust in the technology and in the watchdogs charged with overseeing that technology, the regulators say, especially in countries that are new to nuclear and at a time when people are losing faith in global and national institutions.

“I think we face something of an epistemic crisis where really, in our public dialogue, we’re having a hard time telling truth from fiction, and that permeates the entire culture, including that of nuclear regulation,” Hanson said.

“There’s no silver bullet to get us out of that situation … we have to understand that too and think of new and novel ways of communicating the technical expertise that we have. It’s hard to imagine a path forward to new nuclear deployment without that trusted regulator and without some form of public trust going forward.”

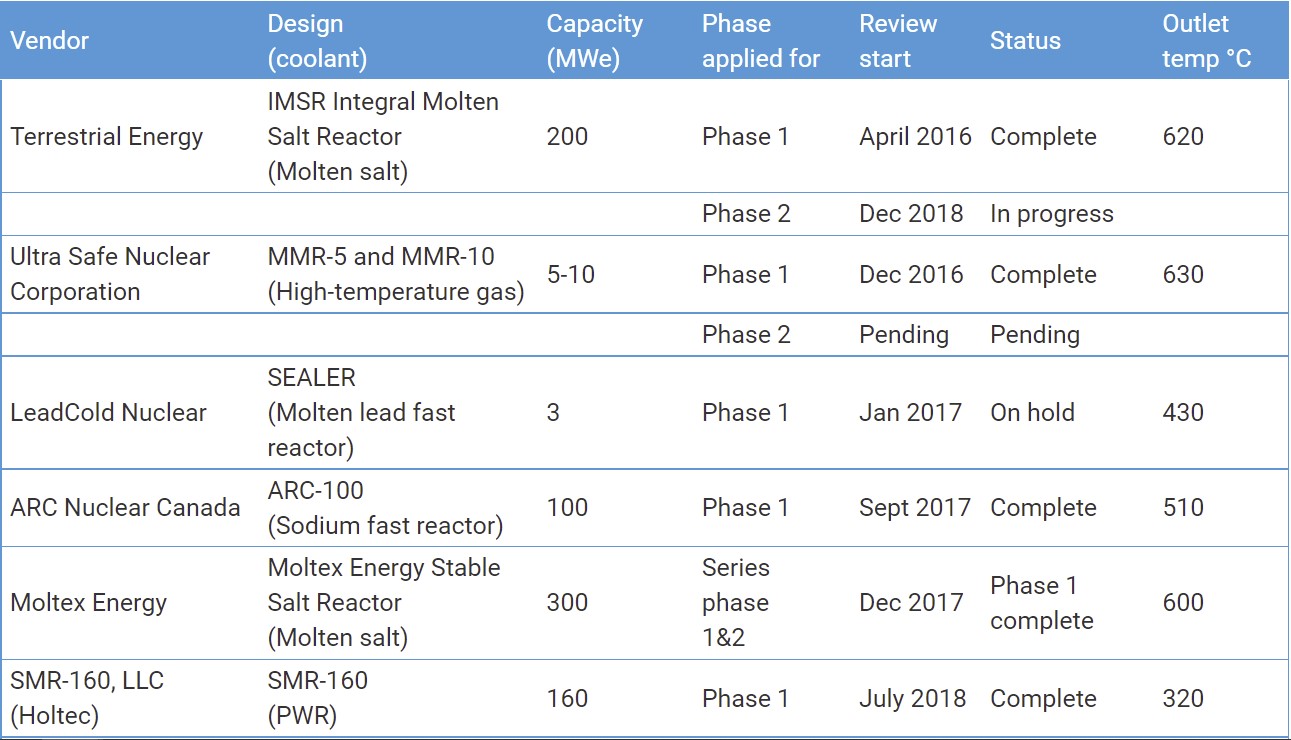

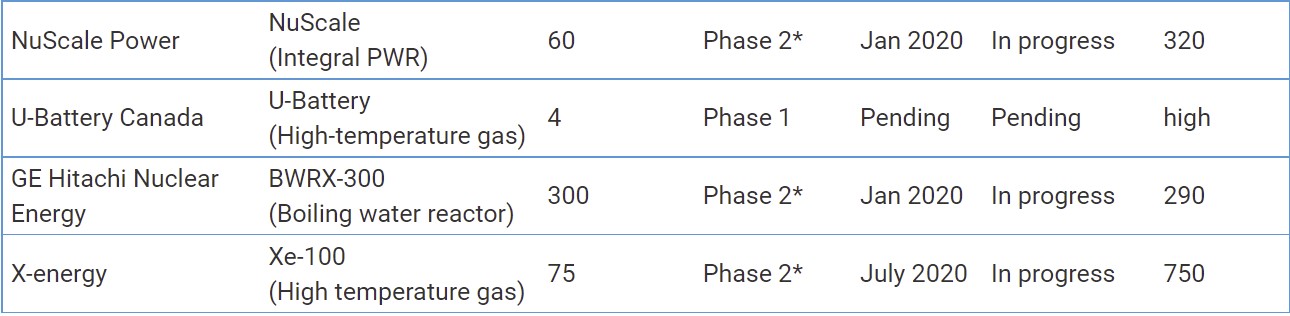

New Small Reactor Designs

(Source: Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and companies; compiled by World Nuclear Association)

Lessons from the pandemic

The global health regulators’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the record speed vaccines were approved, serve as an example to the nuclear community of the importance of deeper collaboration with licensees as well as other international regulators, Velshi said.

“When we had to do our oversight in a virtual space, more remotely, we had to depend on our licensees a lot more, in them opening up their systems, their processes, their databanks, their logs, sending us videos, photographs … so that we could be almost there and see firsthand … access their systems and processes, which required a lot of trust on both sides.”

Work during the pandemic showed that, while a regulator must maintain a certain separation, there was room for more collaboration without compromising that independence as nuclear technology enters a new phase and a world of challenges opens up.

“The MoC in 2019 was absolutely instrumental,” Hanson said.

“I think neither one of us, necessarily, has the capacity to deal with the whole myriad of technologies we were talking about, the tremendous amount of innovation that is going on in that sector.”

After decades of nuclear power generating electricity using technology from the sixties and seventies, the new wave of nuclear reactors – lead by, but not exclusively, SMRs, reactors which close the fuel cycle, and inherently-safe reactors – have forced regulators to raise their workload.

The World Nuclear Association notes that when regulators look at new reactors, just Phase 1 of the pre-licensing review, essentially a technical discussion, involves around 5,000 work hours, while Phase 2, which addresses system-level design, is twice that.

With over 70 SMRs currently in development, the regulators have their work cut out for them.

Each individual regulator can work sequentially on each new piece of new technology presented to it, but opening the process across the border to both regulators brings an extra pair of eyes to every regulatory process, Hanson said.

“While there is some commonality in our regulatory approaches, there’s also some differences. But I think those difference ultimately complement each other because they provide a different lens through which to look at these things,” Hanson said.

Flexible and adaptable

Nuclear power regulators must be flexible and adaptable when licensing new advanced reactor technology as innovative designs test traditional regulatory operations, both said.

Whereas, traditionally, regulators sought to be seen as strong and independent umpires of the nuclear industry, the new generation of SMRs and advanced modular reactors (AMRs) running on new fuel types and designed to be out-of-the-box safe require a more open regulator that can adjust to new technological challenges, Velshi said.

“The big challenge is that there is a lot of uncertainty as to what the future will hold and we want to be prepared for whatever scenario evolves and so … being agile, being flexible, being adaptable have become a key part of our lexicon,” Velshi said

The NRC was focusing on what Hanson called the three “As”; advanced reactors and clarifying a regulatory line of sight for a technology-neutral approach to licensing new nuclear technologies; accident tolerant fuels, which focuses on the safe operation of the existing fleet and licensing new technologies that may be both safer and potentially more economical and; academics, where the focus is on engaging universities and research institutes to join the NRC mission.

“That rapid pace of innovation is really one of the key challenges that we have and understanding the breadth of technological virtues that we are seeing out there for nuclear power and making sure that each one of those has a transparent and predictable regulatory pathway,” the NRC commissioner said.

“We want a comprehensive rule, but we don’t want it to be so comprehensive that people feel hemmed in.”

By Paul Day