Funding round helps kickstart British hydrogen strategy

The British government has announced the first round of funding for clean hydrogen projects and begun calls for the second, setting in motion a strategy which industry says is commendable but must move faster.

Related Articles

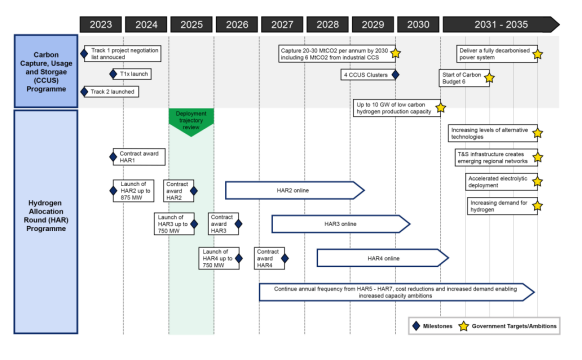

The UK’s clean hydrogen target is 10 GW of low carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, with 6 GW of that from electrolyzers and the rest carbon capture, usage, and storage (CCUS).

By 2025, the strategy is to have up to 1 GW of electrolytic hydrogen capacity and up to 1 GW of CCUS enabled hydrogen in construction or operation.

By comparison, Britain currently has around 5 MW of electrolyzer manufacturing capacity, according to RenewableUK, or just half a percent of what’s targeted for next year, though money has started to move for clean hydrogen projects.

“We commend the government on the foundations that it's put in place, and the efforts that it's made to get this started,” says Celia Greaves, CEO of the UK Hydrogen Energy Association.

“However, there's a lot still to do, and I think we need to move further and faster, particularly if we want to meet our targets.”

In December, the government announced the first run of government-aided projects under the electrolytic Hydrogen Allocation Round (HAR1) worth 125 MW.

The 11 new production projects, which will invest around £400 million over the next three years as part of the government's £2 billion funding over the next 15 years, was hailed as a significant milestone in the development of the UK hydrogen economy.

“They represent a shift from policy development to project delivery, giving industry more clarity on the route to final investment decisions,” COO of Hydrogen at RWE Generation Sopna Sury said in a statement.

Part two of the allocation round, HAR2, for which applications must be submitted by April 19, 2024, will be considerably larger, worth up to 875 MW, while HAR3 and HAR4, expected to be launched in 2025 and 2026 respectively, will aim to allocate a further 1.5 GW.

While HAR focuses on boosting production, another program, the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (NZHF) worth up to £240 million, supports projects across the clean hydrogen value chain.

The NZHF rounds are focused on two areas, with strand 1 aimed at early development stages of hydrogen projects, covering front end engineering design (FEED) studies and post-FEED development activities, while strand 2 focuses on supporting projects ready for construction, providing capital expenditure for building facilities.

The UK hydrogen strategy aims to cover all the bases, with the HAR funding mechanism bridging the gap between the cost of producing clean hydrogen and fossil-fuel methods, and the NZHF’s wider focus of production, storage, distribution, and end-use applications of hydrogen.

Hydrogen Production Delivery Roadmap

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Uk Department of Energy Security & Net Zero: Hydrogen Production Delivery Roadmap

Much to do

The government’s approach is three tiered and encompasses the challenges of energy security, moving towards net zero, and clean growth, says the UK Hydrogen Energy Association.

Finding the balance is important to develop the industry from the ground up and to avoid importing all the technology that will be needed, says the association’s head.

“We've got a vision of up to 35% of our final energy demand being met by hydrogen in 2050, so we've got a huge mountain to climb. But that's an exciting opportunity if we can get hold of it and progress things properly,” CEO Greaves says.

The dual subsidy framework helps, on the one hand, to support the development of capital expenditure and put shovels in the ground to build the projects, while on the other hand, to de-risk the operation through price support mechanisms.

The winning projects have a wide scope that aims to establish the new industry’s foundation, with the NZHF helping build the infrastructure through capital expenditure (CAPEX) support, and the HAR focused on making clean hydrogen a viable alternative to fossil fuels by providing contracts that guarantee prices.

The 11 projects under the HAR1 round have been agreed at a weighted average strike price of £241 per megwatt hour (MWh).

Greaves notes that further production ambition will be needed, as well as a much more synchronized approach linking production, transportation, storage, and use.

“There's all sorts of detail in there in terms of how we can make that better, which industry wants to see, and which will help us deliver on hydrogen’s potential across net zero, clean growth, and energy security,” she says.

The details

For an industry at the very start of its life, the details will likely be what helps it grow or stops it in its tracks.

Britain has taken a phased approach to the definition of clean hydrogen, releasing its Low Carbon Hydrogen Standard in 2023 while aiming to update the Standard at regular review points.

In the United States, concerns have arisen that overly strict regulation could hurt the industry and the debate has put billions of dollars of subsidies on hold until the definitions can be agreed upon.

U.S. legislators are currently tied up in putting a final definition of what can be considered clean hydrogen and, consequently, who is eligible for state aid.

The debate is focused on when and where to source the electricity to run the electrolyzers – off the grid or via new installations – and how much carbon dioxide can be emitted in the process.

The UK, meanwhile, has made sure the definitions were mostly in place before the subsidies could be allocated. For the moment, the Standard has set maximum carbon intensity thresholds of 20 gCO2e/MJ, though this may change.

How this compares to other definitions is unclear but aligning the UK’s standards with that of its largest commercial partner, the European Union, will be an important next step.

Other challenges include stimulating demand – the UK has yet to set use targets for transportation and industry, focusing primarily on production – and making sure timescales are synchronized for factors such as infrastructure development, transportation and storage, and permitting and licensing.

By Paul Day