UK looks to cut new build costs by almost a third by 2030

A Nuclear Industry Institute (NIA) report outlines how to cut new build costs by 30% over the next 10 years, as industry heads warn the negative perception of nuclear means expensive financing.

Related Articles

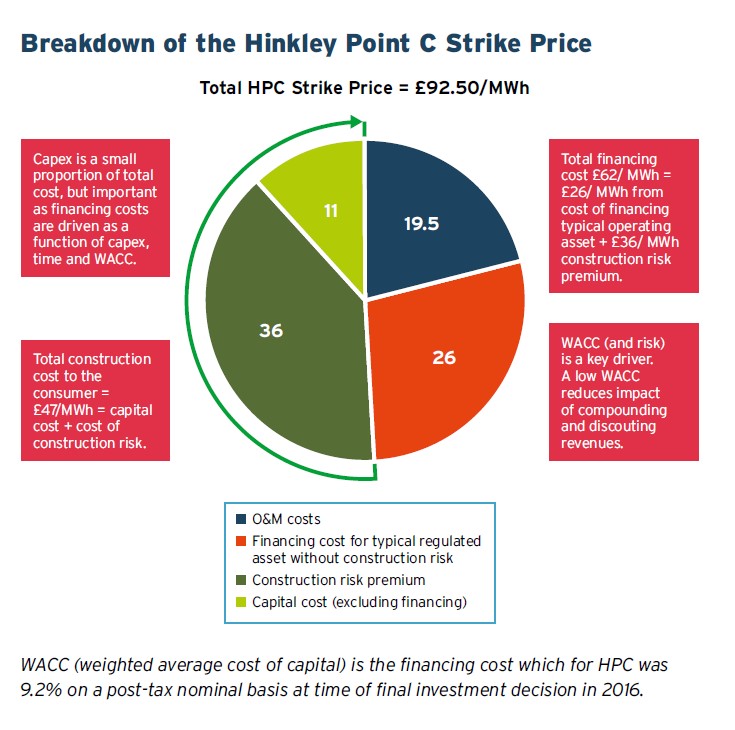

The British government’s Nuclear Sector Deal used Hinkley Point C (HPC) strike price of £92.50/ MWh as a baseline for the cost reduction and put together the New Build Cost Reduction Working Group to find a way to achieve this goal.

In a break down of HPC’s EPR reactors, which EDF adapted from similar technology in France for Britain, two thirds (£62/MWh) of the cost to the consumer came from financing the build, of which more than half (£36/MWh) was used to cover the project’s risk premium.

Reducing construction risk and capital cost would be key to meeting the goal, the group said.

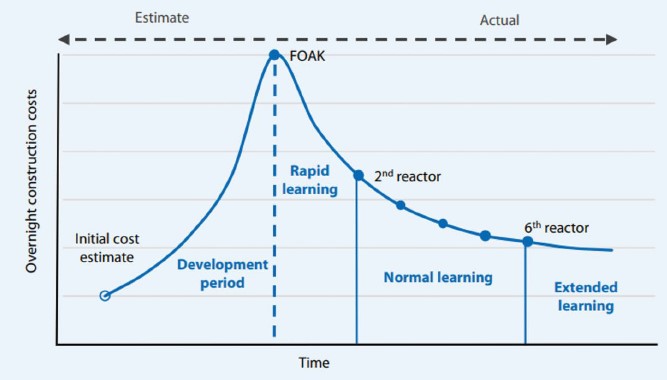

Meanwhile, another recent study showed how the industry needed to be mindful that first-of-a-kind (FOAK) projects were always going to be more expensive than nth-of-a-kind (NOAK) while high level industry heads asked how governments and investors in liberalized energy markets could finda way to ease perceived financial risk.

(Source: Nuclear Industry Institute)

(Source: Nuclear Industry Institute)

Before building starts

Using an international database of 530 industrial megaprojects, the Working Group pinpointed 14 factors that needed to be delivered to an adequate, or preferably high, standard before construction even started.

- Financing

- Regulation

- Governance

- Site data

- Technology data

- Design

- Estimates

- Contractual interfaces

- Project management

- Data system

- Construction preparation

- Supply chain

- Skills

- Operations preparation

“For each category, the Working Group is developing a scorecard, which will define what low risk and hence construction readiness in each area would look like for a new nuclear power station. This will enable a robust assessment, prior to a Final Investment Decision being taken, of the extent to which a developer has taken the necessary actions to reduce

risk and cost,” the report said.

Sufficient early planning and the use of a mature design before construction even begins improves cost, schedule, operability and safety, the group found, while a programmatic approach was key as savings can be made building a number of units of the same design.

The Nuclear Cost Drivers Study, prepared by Lucid Capital for the Energy Technologies Institute, leaned on the experience of nuclear plant builders all over the world.

The study found that once a developer had moved beyond its FOAK project, replication of designs and reusing established supply chains helped considerably in reducing costs.

HPC pricing has suffered from being the first EPR project in Britain and is also the first of a generation of new nuclear in the country, forcing its developers to reestablish the supply chain and train workers.

“The UK can readily benefit from the deployment of multiple reactor designs, but only if each of these designs has multiple reference projects and is replicated in a series build to enable cost and risk reductions to be delivered between projects,” the report said.

This has been a primary argument of proponents of the planned Sizewell C plant in the UK. Sizewell C aims to be an almost carbon copy of HPC, and supporters of the project argue that, while the Somerset plant may have overrun in time and costs, the second near identical plant would leverage the experience from HPC so keeping costs lower in Suffolk.

The Strike Price for Hinkley Point C would fall to £89.5/MWh at 2012 prices if EDF were to take a Final Investment Decision on Sizewell C, the French utility has said.

Beyond fleet deployment, other key cost-reduction strategies include the use of advanced construction methodologies, design for low-cost delivery (passive safety designs and the use of previously licensed technology) and innovative designs, such as advanced and factory-ready small modular reactors.

Nuclear also needed to learn from other construction projects and new ways in which they have cut costs, such as 3D modelling, which enables virtual plans to be written up to avoid bottlenecks and find potential pinch-points in construction schedules.

The cost of risk

Financing costs take up nearly two thirds of any nuclear project’s final price for consumers and developers, and governments and stakeholders are looking at various models that might help shrink that cost.

Financing costs, in a liberalized market, are directly linked to risk and confidence, and it is partly this that has kept lending prices sky high.

The OECD’s Nuclear Energy Agency report “Unlocking Reductions in the Construction Costs of Nuclear: A Practical Guide for Stakeholders,” found that stakeholder and public confidence in the ability of the nuclear industry to build new projects had been eroded.

“The perception that new nuclear plants carry high project risk dissuades investors and has further reduced the ability of countries to attract financing for future projects. These issues are not present in countries that have been building plants continuously,” the report said.

In countries with a constant churn of nuclear build, experienced project organizations and well-established supply chains meant projects are on time and on budget, it said.

“This suggests that the challenges experienced by many FOAK projects are not inherent to the nuclear technology itself but rather depend on the conditions in which projects are being delivered and on the interactions among the various project participants involved,” the report found.

Nuclear New Build Learning Curve

(Source: OECD adapted from Yemm et al. (2012), "Pelamis: Experience from concept to conception)

In a World Nuclear Association webinar mid-September, stakeholder confidence was named one of the main drivers behind whether a project might hold within, or overshoot, budget constraints.

“Inconstant commitment by governments to nuclear technologies can make conditions for nuclear generation very uncertain and this can also result in not achieving economy of scale that should be available in the nuclear generation sector. Then the ability to bring costs down over the long term has been missed,” Jostein Kristensen, partner at energy consultant Oxera, said.

Apples and Oranges

While FOAK factors and financial and political risk were widely agreed to pile on costs for the sector, some during the WNA webinar questioned whether nuclear generation should even be measured in the same way as other power generating technologies.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is the standard way of comparing two power producing technologies – it does not matter how the power is generated but how much will it cost the end user. However, some claim that this approach is like comparing apples and oranges.

“Using LCOE to compare generation costs has become widespread practice, however the approach based on LCOE associated with different generation technology or any other measure of total lifecycle production costs per megawatt hour provided does not take in to account different system costs,” said Leonam dos Santos Guimaraes, Director for Planning, Management and Environment at Eletronuclear.

This effectively treats all generated megawatt hours, regardless of source, as a homogenous problem of a commodity of a single price, which electricity is not, he said.

The cost does not measure the value, dos Santos Guimaraes noted, an argument that is being increasingly put forward as the world attempts find a way to eliminate greenhouse gases and become carbon neutral without endangering industrial growth and progress.

“It would be like saying a car costs a lot more than a bicycle so we should all buy bicycles. This disregards that cars and bicycles are providing services of different natures,” he said.

By Paul Day