Community wind set to combat Europe's permit crisis

The financial closure of Europe's largest community wind farm shows how local stakeholders can expedite permitting and lure investors, project partners told Reuters Events.

Related Articles

In June, a Dutch cooperative of 200 local farmers, residents and investors, closed the financing and turbine supply contracts for the 322 MW Zeewolde wind repowering project near Amsterdam.

Due online in 2021-2022, Zeewolde will be the largest onshore wind farm in the Netherlands and the largest community-owned wind farm in Europe. Denmark's Vestas will replace 220 turbines at the site with 83 larger turbines of capacity 2 MW and 4 MW, tripling the energy output.

Rabobank agreed to provide 500 million euros ($561.5 million) of junior and senior debt to the project. In late July, Nederlandse Waterschapsbank (NWB Bank) and Danish export credit insurer EKF agreed to co-invest under a refinancing.

The community structure helped minimise permitting issues and stakeholders showed early financial, as well as ethical, commitment, project partners told Reuters Events.

Funding from community stakeholders allowed the construction of the substation and foundation works to begin in October 2019 and this helped secure investors.

"The stakeholders had already shown commitment to the project by carrying out those early works,” Leonieke Blaauwgeers, Account Manager Project Finance, NWB Bank, said.

“That increased our confidence in the project,” she said.

Permit push

In Europe, permitting is a major challenge for wind developers, particularly for larger turbine sizes.

Public opposition against visual and noise impacts can derail projects and permitting can take years.

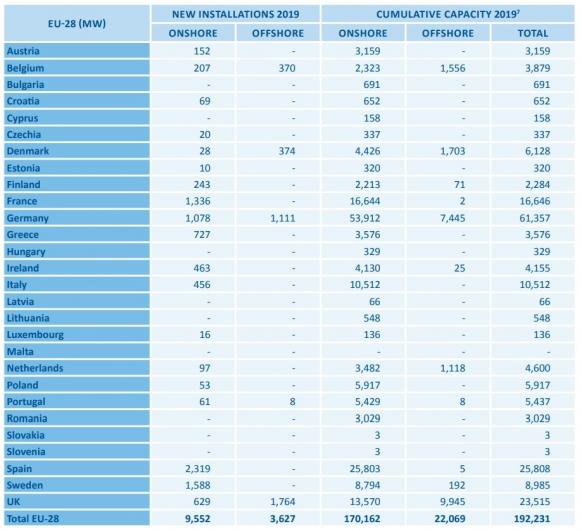

In Germany, Europe's largest wind market by installed capacity, permitting issues have severely dented growth. In 2019, Germany installed just 1.1GW of new onshore capacity, compared with an average 4.6 GW per year in 2014-2017, data from industry group WindEurope shows.

Onshore wind permitting currently takes over two years, compared to an historical average of 10-months, according to data from BWE, Germany’s wind industry association.

Europe wind installations by country in 2019

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: WindEurope

Community stakeholders reduce the potential for public opposition but the Zeewolde partners still prioritised permitting early in the development phase.

The project was created in 2013 and permitting work began in 2015. Some parties launched lawsuits against the project but by 2019 the permits were irrevocable.

“Nobody, neither at corporate or community projects wants to commit large amounts of money until the permits are there and are strong,” Sjoerd Sieburgh Sioerdsma, Managing Director of the project, said.

Early permitting meant the project received “meaningful turbine supplier quotes in the absence of project track record,” he noted.

Community stakeholders also help to encourage permitting authorities.

"Governments are willing to progress projects because they recognize these projects as being in the common interest of society,” Sieburgh Sioerdsma said.

Investors are also attracted to community projects due to social responsibility benefits.

“The community make-up is an important element for NWB Bank,” Blaauwgeers said. “Social support from citizens within the development area is ensured, dissipating reputational risks that a lender must factor into its assessments.”

Local threats

The large number of stakeholders in community wind projects can create challenges for developers, requiring signoff by more parties.

The Zeewolde partners managed to align the interests of the large number of stakeholders over several years, even through "difficult times," Pieter Plantinga, Executive Director Project Finance of Rabobank, told Reuters Events.

"We have seen smaller projects where this has been a lot more difficult, including a series of three projects in Drenthe province, in the northeast of the country,” Plantinga said

In Drenthe a number of stakeholders withdrew from community wind projects after threats and intimidation from objectors.

In late-2018, the Netherlands counterterrorism unit identified anti-wind farm activists as a new group threatening public safety.

"At local level citizens have protested the construction of wind farms by democratic means, but in the provinces of Drenthe and Groningen in particular illegal forms of protest have occasionally been employed," the unit said in a report in September 2018.

"The protests were directed against officials who support wind farms, farmers on whose land wind turbines are being erected and businesses that build and install wind turbines," it said.

External operations

Where possible, the Zeewolde project team has looked to outsource long-term contracts to third parties.

“Turbine O&M, PPA management, asset management - it’s all outsourced,” Sieburgh Sioerdsma said. “The cooperation has only one major project so it does not make much sense to build inhouse resources and processes for one project."

Vestas has signed a bespoke 20-year service contract, which helped "provide predictability to the banks," Sieburgh Sioerdsma said. OutSmart BV, a Dutch subsidiary of Deutsche Windtechnik, will supply asset management services and the owner has secured a 16-year power purchase agreement (PPA) with power supplier Vattenfall.

The PPA largely mimics the Dutch renewable energy subsidy scheme, which compensates the power generator for differences between contract price and wholesale market price.

Missing upgrades

As turbines age, operators must choose between repowering the site with larger turbines, extending the lifespan of the existing turbines, or decommissioning the facility.

Permitting hurdles and a lack of support regimes have limited the appetite for turbine repowering in Europe. Repowering projects allow countries to increase renewable energy capacity without developing new land, but only Italy has implemented specific incentives for repowering projects.

Only 185 MW of 11.7 GW of new onshore capacity installed in 2019 were repowering projects, WindEurope data shows. In contrast, around 4 GW per year could be ripe for life extension in the next 10 years.

Wind turbine ages by country

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: WindEurope, August 2018.

Group power

Community structures can help spur demand for wind projects, including repowering, and some countries have attempted to incentivise these initiatives.

In 2017, Germany allowed community wind projects to bid into auctions without permits, but these advantages were removed in 2018 after community groups won the majority of capacity. As a result, community wind activity plummeted as developers were exposed to stricter permitting and construction rules.

In the Netherlands, only a fraction of wind capacity has been installed by community-based projects. However, the Dutch government wants community ownership to increase and will require wind and solar projects online from 2030 to be at least 50% owned by local communities.

“We expect that the Dutch community will unite increasingly in such cooperatives,” Blaauwgeers said.

Rabobank is already seeing more community projects being approved in the Netherlands.

Even on larger projects, communities are instigating development work to steer local involvement control project impact, Plantinga said.

"They find it important that the community is involved and embraces the project," he said.

Reporting by Kerry Chamberlain

Editing by Robin Sayles