New tech key for Bruce Power MCR project

Vision positioning, automation, and robotics technology, as well as finding and training a highly specialized and skilled workforce, have been vital in keeping Bruce Power’s Major Component Replacement (MCR) project on schedule, industry heads say.

Related Articles

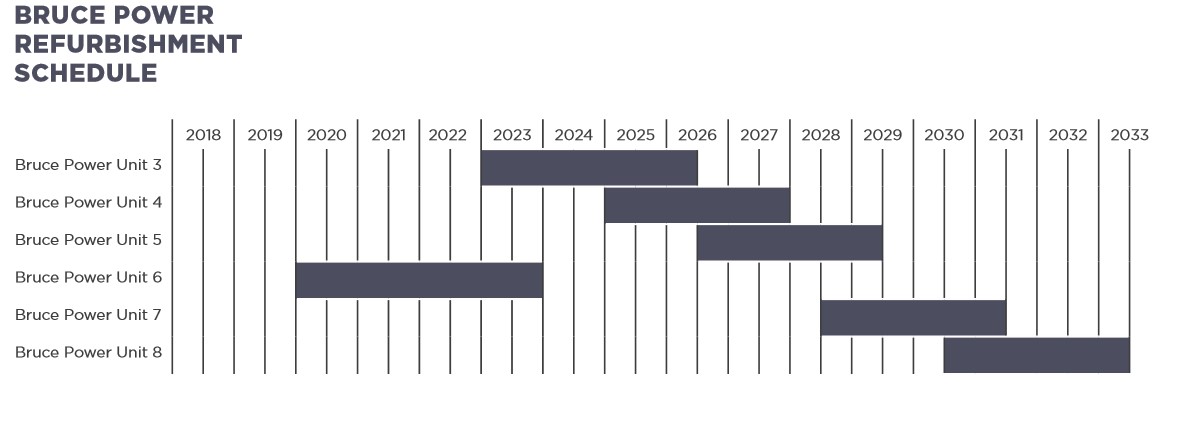

Canadian nuclear power plant operator Bruce Power began the 13-year MCR-phase of its life extension program for its 6.5 GW power plant earlier this year and aims to refurbish and replace the remaining six of the plant’s eight reactors to extend its life by 30-35 years to 2064.

The company is using the overhaul to modernize and update much of the plant.

“The MCR is the visible tip of the iceberg of what we’re doing; We’re extending the life of all our eight units, with the current focus on the six units that have not yet been refurbished. It’s as if we’re keeping the shell of the power plant, while changing everything inside,” says Bruce Power Executive Vice President of Projects and Engineering Eric Chassard.

A large part of the project is fully automated, says Chassard.

“It’s all about automation, robotics and the dedicated team who have designed, built and now operate these innovative tools,” he says.

(Source: Bruce Power)

Virtual Reactor

ATS Automation’s multi-year tooling agreement with Bruce Power has played a large part of the process, designing and operating tools built to safely remove irradiated reactor components, and has built a 43,000 square foot (almost 4,000 square meters) MCR facility for testing, verification and optimization of the removal, inspection, and installation tools.

“This really mimicked the reactor environment so we could test all the tools, do full process testing and training at ATS for the MCR program,” says General Manager for Nuclear at ATS Automation, Narinder Bains.

ATS Automation has leveraged its knowledge base from transportation, life sciences, consumer products and electronics and applied it to the job of overhauling Bruce Power’s plant.

The development of real time vision systems, whereby a remote operator can observe the automated system in action, has helped apply ATS Automation’s know-how to the challenges of modernizing a plant that generates almost a third of Ontario’s electricity.

“You can pre-program our machines to get you to certain locations but the components that you are trying to remove could be in a slightly different position than you expected, so you need real time vision system to target these fuel channels so the machines can be absolutely aligned,” says Bains.

ATS uses a specialized automation system of multiple machines, all controlled by a remote, integrated control system, for the complex task of the removal of the highly radiated fuel channels while an operator, sat in front of a multitude of screens and with the power to stop the process at any time, offers oversight.

Most of ATS’s engineers come from conventional automation sectors, so the group developed a specialized internal nuclear group, headed by nuclear experts like Bain who has been in the industry for 30 years.

“We’re ensuring that we’ve got that tribal nuclear knowledge that we need to understand radiation and how you need to operate and work in that environment and, coupled with our conventional engineering design capabilities, we can leverage both of these together to successfully deliver the MCR program,” he says.

SNC Lavalin, which is working with Bruce Power via its wholly-owned subsidiary Candu Energy Inc. and helped refurbish Units 1 and 2 previously, says the operational experience gleaned on previous jobs has greatly improved safety, human performance, quality and its own tool set for its work on the remaining units.

“Before, an operator would have to guide some of the these tools in to place by eye but we’ve updated them with enhanced vision positioning systems which are automated and which can precisely place the tool to the face of the reactor,” says Bill Fox, President & CEO of Candu Energy Inc.

A digital twin

Any new technology, process or system, like any engineer, must first be trained and put through its paces before it can be turned on a real world nuclear power station, and digital twin technology has proved invaluable for ATS Automation.

The technology creates a virtual model for any process or system, on which new engineers, or freshly minted robots, can practice.

Multiple automation tools working on the plant need a system of oversight, with around 20-30 operators working 24/7, and all those people need to be trained.

“We’ve built multiple digital twin models of every tool so that you can release 3D models of these tools coupled with the human-machine interface that the operator sees at the control station,” says Bain.

The virtual machine acts as realistic training program which can be set up for trouble shooting scenarios, such as if the machine stalls.

Candu Energy has also found the development of virtual and augmented reality workspaces invaluable for training.

“We’ve put some of this technology on craftsman within the training facility to give them a view of their workspace in a very safe and well protected environment. It’s like the craftsman has done the job a hundred times before by the time he reaches the reactor,” says Fox.

Finding the Staff

Finding qualified staff has been one of the greatest challenges for BWXT Canada, one of the largest manufacturers and service providers on the project. The nuclear components supplier is providing some 32 steam generators as well as heat exchangers, core reactor components, waste container as well as inspection and construction services.

“The biggest challenge has been to scale up. We’ve seen significant growth in personnel and in our plant capacity for all equipment that we have,” says John R. MacQuarrie, president of BWXT Canada.

“Welding in particular is a very unique skill set. Nuclear class welding is the most difficult welding because it’s the most highly inspected so if you’ve got any kind of problem with the weld you’ve made, we’re going to find it,” MacQuarrie says.

The company has met the challenge by starting its own training school where they create mockups of the parts of the component and have the trainees weld them before putting them through the real thing.

By Paul Day