Reuters Events Sustainable Business editor Terry Slavin and Tim Nixon of Signal Climate Analytics launch a year-long partnership shining a light on what the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters are doing in the battle against climate change

About one third of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions can be pinned directly on just a few hundred companies, the biggest players in the energy, transport, mining, manufacturing and consumer goods sectors.

The direct and indirect emissions of these industrial giants are huge in themselves, but due to their vast market share, marketing and lobbying power and extended supply chains, they wield enormous power over sector peers, regulatory frameworks and even consumer attitudes about climate change.

Unless these critical actors take steps to rein in their emissions, we are unlikely to succeed in keeping global temperature rises to no higher than a 1.5C increase on pre-industrial times, the limit that the 2018 IPCC report tells us offers a safe operating space for the planet.

In The Ethical Corporation magazine we have been highlighting the companies that are working to transform their business models to operate within planetary boundaries by joining initiatives like Science Based Targets (SBT), including the new Business Ambition for 1.5C coalition, to which 385 companies have already committed.

But as we reported in the December issue, there has been no mechanism for systematic third-party verification or for companies to report transparently on how they are actually performing against their targets – although the SBT will be introducing a global standard to provide this at the end of this year.

Meanwhile, there has been a proliferation of many more companies setting net-zero targets with a reliance on offsetting rather than cutting emissions in line with science, with research from South Pole finding a “major chasm” between net-zero ambition and concrete action.

There is also the risk that positive action by a few hundred self-selected companies, even though they include some of the world's biggest brands, can deflect attention from the need for all companies to step up, starting with those that bear the biggest responsibility.

Over the next 12 months Reuters, in this magazine and on Reuters.com, will be embarking on a data-driven inquiry, with our partner, Signal Climate Analytics, looking at the companies on which most of the world still depends for its everyday energy, travel, food and shelter.

We will seek to answer two key questions. First, how transparent are they about their total GHG emissions and related environmental impacts? Second, are they transforming their business models fast enough to avoid the worst consequences of an over-heated planet?

Full transparency is a starting point but meaningful change requires the transformation of key processes, products and potential business models that have themselves brought these firms to the pinnacle of success. It’s a daunting challenge, but an essential one. Informed stakeholders, including corporate executives, investors and asset owners, policymakers and advocates need to play their role.

Doing so effectively requires a thoughtful look at the current state of transparency and transformation among these carbon-intensive giants, looking back over trends in the recent years and to the critical decade ahead.

Talking the talk

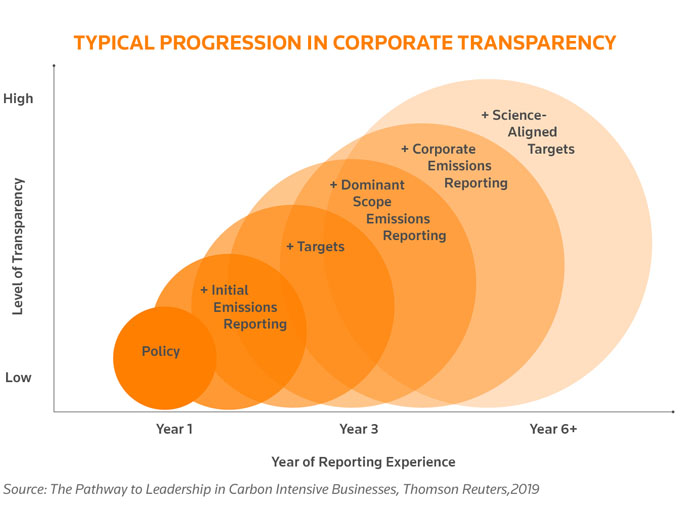

For the past three years, Signal Climate Analytics has worked with Reuters to assess the progress the world’s industrial giants have made in increasing transparency on climate change. As shown in the chart above, most large businesses appear to follow a predictable pathway, beginning with adopting a public policy on addressing climate change, moving to systematic measurement and disclosure of all direct and indirect emissions, and ending with setting science-based emissions reduction targets. It’s a process that takes years, and is far from uniform. There remains a sizable gap between what we know and need to know to protect our planet.

But it is on that basis that we have identified 25 publicly traded companies, organised by sector, that are among the biggest corporate sources of climate-warming emissions (see chart below).

The companies, which together account for more than 10% of global annual anthropogenic emissions, made the list based on the size of emissions across all scopes and because, as publicly traded entities, data on their businesses can more readily be obtained from corporate disclosure.

The list predictably includes the world’s biggest oil and gas companies, coal producers, mining firms and steel producers, but also German automaker Volkswagen and U.S. diesel-engine manufacturer Cummins. Most qualify due to the outsized impact of their scope 3 emissions, the emissions their products make in use.

The chart also shows that while many of these 25 firms are approaching full disclosure of their emissions footprint, most do not disclose what their plans are going forward to reduce their emissions.

BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Thyssenkrupp, Vale and VW are showing leadership by disclosing plans, although not always including all scopes, to decarbonise by adopting 1.5C aligned science based targets. Others, including ExxonMobil, NK Lukoil and Gazprom are further behind, though they are taking important steps in a process that is often a prelude to the actual transformation of their businesses.

Investors are increasingly driving this change, as we’ve seen recently with ExxonMobil, which before Christmas promised to cut emissions for every barrel of oil by up to a fifth over the next five years, after investor pressure from activist investor Engine No 1, backed by heavyweight institutions like the Church Commissioners for England and US hedge fund DE Shaw.

Walking the walk

Transformation is where companies begin to systematically transform their core products, processes – and in some cases business models – to satisfy their customer needs and wants, with solutions that reduce or eliminate harmful environmental or climate change impacts.

One example of a company on this path is U.S.-based Cummins, which has set transparent GHG reduction goals and implemented a transformation strategy to achieve them. Cummins is investing meaningfully in a new power segment, combining the company’s electrified powertrains, fuel cells and hydrogen production technology. Over the last three reporting years, GHG emissions across all scopes fell 7% while revenue increased by 15%. The company also reported record profitability in 2019.

Cummins is a signatory to the Science Based Targets Business Ambition for 1.5C coalition, but for firms not yet sure how fast or far they can move, the transformation process begins with more active experimentation with lower-carbon products and processes.

The initial goal for most is to reduce the carbon intensity of their revenue base, i.e. the grams of CO2 (and CO2e) per dollar of revenue. For these firms, emissions may still be going up, but more slowly than revenues. The ultimate transformation objective is to decouple emissions from revenues on an absolute basis so that emissions keep falling at an increasing rate as revenues rise, ultimately putting them on a 1.5C trajectory.

Measuring transformation

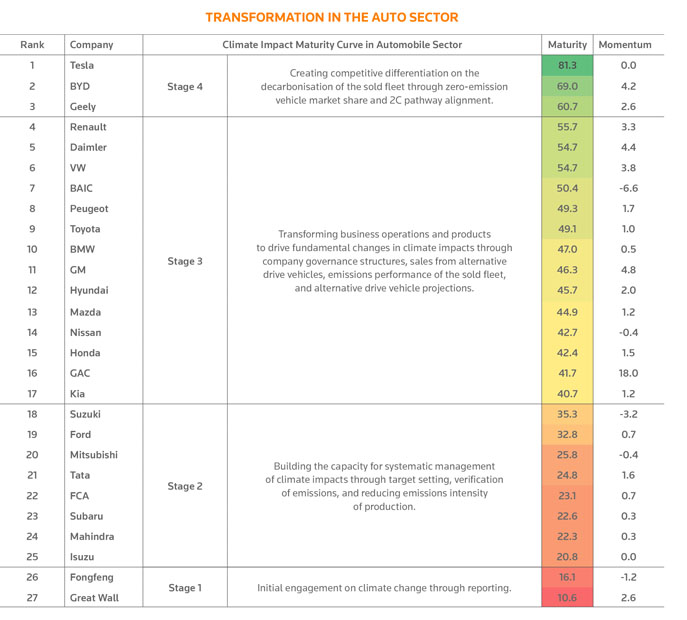

Measuring transformation involves integrating data on disclosure with company industrial benchmarking, production and projection data to create a composite picture of where a company has been and, most importantly, where it is headed. To demonstrate this process in action, we have applied this methodology to the largest manufacturers in the automotive sector.

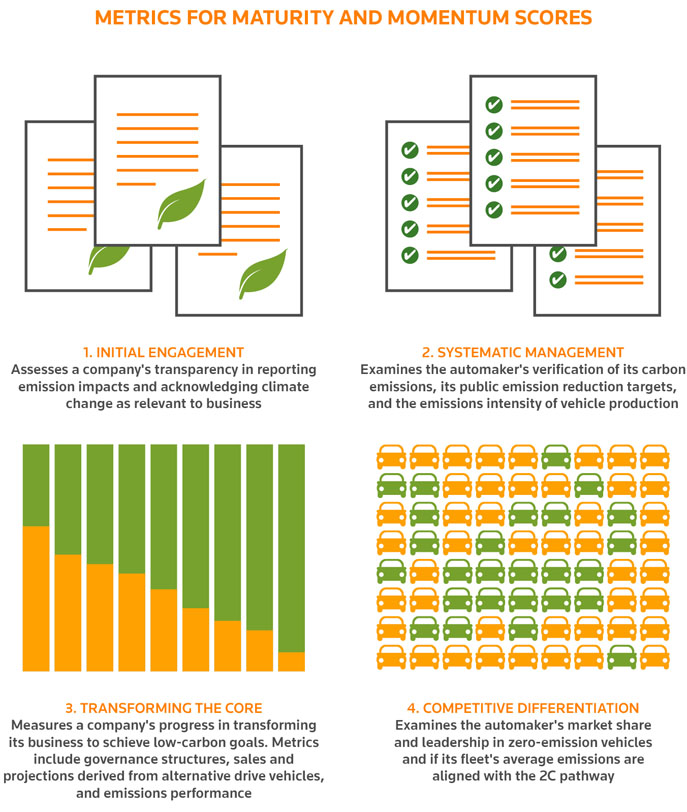

As described in the two graphics below, the analysis is split into four stages and takes into account more than 50 metrics, including a company’s willingness to report emissions and targets (disclosure), its market share in zero-emission vehicle sales, and whether its production plans are aligned with the 2015 Paris Agreement goal of limiting global temperature rises to "well below" 2C. A maturity and momentum score is then assigned to determine an automaker’s rate of progress in decarbonisation.

The maturity score measures how much an automaker is innovating and if it is showing continuous commitment to decarbonise. The momentum score measures the rate at which maturity is changing over time. While past performance cannot be assumed to predict future results, it does indicate how much some companies need to pick up their pace to contend for leadership.

New market signals

As much as any incentive, new signals from the market may drive the rate of decarbonisation in a sector. As the return on investment in transformation rises, so could the likelihood of meaningful decarbonisation in carbon-intensive business models. As transition risk and transition opportunity become apparent and are measurable at the company level, new levers to accelerate transformation may emerge.

How market signals, such as shareholder return or cost of capital, align with other drivers, such as regulatory pressure and consumer preference, will influence the rate and scope of decarbonisation in the world’s carbon-intensive sectors.

Reuters and Signal Climate Analytics will continue to measure and report on these indicators across some of the largest carbon-intensive business models in the year ahead.

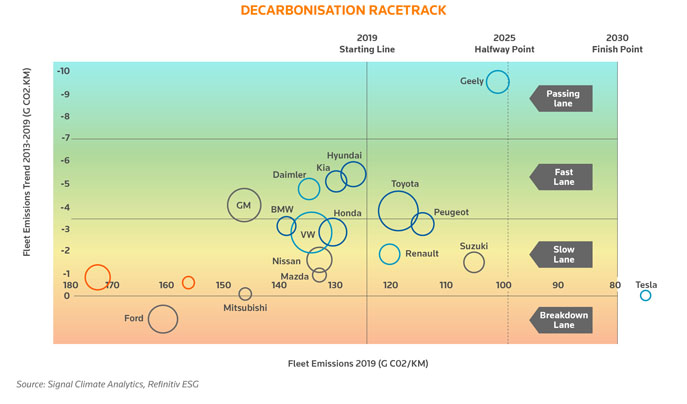

And of course, it’s important to understand not just how these companies are performing relative to each other but also compared with planetary boundaries. In the graphic above, we find the auto sector plotted with companies higher up in the graph decarbonising more quickly, and those farthest to the right, approaching the finish line with a carbon footprint in line with the Paris accord. There is already a long way to travel for most firms, with an even longer and steeper road as policy adjusts to a 1.5C target.

The year ahead for Big Carbon

This will be a pivotal year on the climate scene, as Big Carbon is pushed harder than ever to become better for our global economy and planet. The new Biden administration will bring the United States back to the regulatory discussion, and market signals are likely to continue to increase the transition opportunity for the innovators and the risk for the laggards.

Reuters and Signal Climate Analytics will be providing monthly data-driven updates on the trends within the largest carbon-intensive business models, with a specific focus on those firms that are big enough to change the course of global progress, one way or the other. We are excited to bring this new quantitative approach to our climate coverage and look forward to welcoming readers to this discussion at such a crucial time.

This article appears in the January 2021 issue of the Sustainable Business Review. See also:

Policy Watch: President Biden sets about tackling climate change with ‘all-star’ team

Brand Watch: U.S. oil majors feel heat as climate divide widens with European competitors

ESG Watch: Investors urged to set science-based climate targets, and join UN’s race to zero

Interview: How WEF converts blue-sky thinking into real-world action

‘Many countries are saying no more internal combustion engines. The U.S. needs to say it too’

GHG emissions Science Based Targets Business Ambition for 1.5C net-zero fossil fuels automotive industry Cummins