Comment: Delphine Gibassier of Audencia Business School says Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model, adopted by Amsterdam and in France, shows how business can stay within planetary and social boundaries

For more than 50 years now, numerous actors from the accounting profession and outside have been calling for a change in the way we account for performance and value-creation. A major step forward was taken when integrated reporting was tested, written and published between 2010 and 2013. For the first time, a new vocabulary insisted on different capitals (six according to the framework) to be taken into account, as well as long-term value creation, and connectivity.

Since then, over 1,500 reports have been published worldwide, with two countries leading the way (South Africa and Japan). The Big Four accountancy firms, as well as pioneering companies such as The Crown Estate, or Kering, have innovated and created different types of multi-capital accounts. According to the Value Balancing Alliance, over 300 of them have been tested in different companies worldwide (about 40 are public).

The Covid-19 crisis has called for these experiments to be taken a step further. Why would multi-capital accounting become even more crucial now then a few weeks ago? The crisis has revealed several key features that are requested from the new accounting that all organisations, not just a handful, should implement.

Covid-19 has temporarily weakened ‘the tyranny of the status quo’, creating a context in which radical, systemic change is suddenly possible

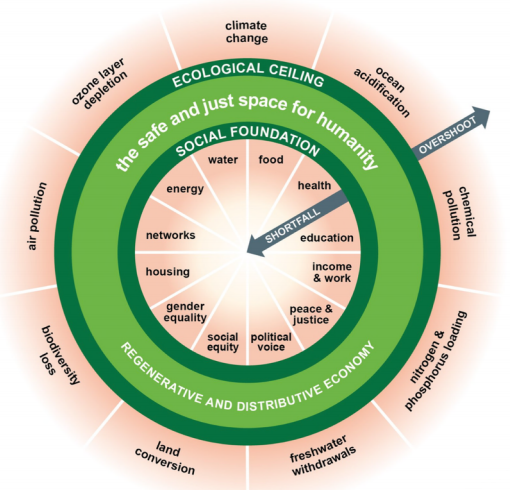

Of course, accounting should be multi-capital. It should also be connected (through system thinking), long-term and future oriented (in opposition to current accounts), and rooted in Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model, which integrates social and planetary boundaries. As John Elkington argues elsewhere in this issue of Ethical Corporation: “Covid-19 has temporarily weakened what Milton Friedman called ‘the tyranny of the status quo’, creating a context in which radical, systemic change is suddenly possible.”

It’s high time to call for a radical new accounting and a radical new accounting profession.

Connectivity of different “capitals” is not something easy to actually perform in a reporting format. The “octopus” value-creation figure from the integrated reporting framework portrays the capitals as parallel, with no connections, and it is rare to see any trade-offs between capitals mentioned in reports. However, the response to the crisis has demonstrated that thinking in “systems”, in an integrated manner, makes urgent responses possible, but also makes companies more resilient. For example, one could approach value creation in the way that Future Fit defines it, that is “system value”.

Looking for long-term versus short-term is a request we have heard for decades from sustainability specialists. However, the language of business, accounting, is looking at the past.

David Beatty of the Rotman School of Management in Toronto, said in a recent blog that in his view “the creation of long-term, sustainable, differentiated and competitive advantage can be derived only with a strategic time horizon of five years and more”.

Currently, only two frameworks clearly call for a strategic look at the future: the integrated reporting framework and the Task Force on Climate-related Disclosures (TFCD), through scenario analysis. The ACT framework (on assessing low carbon transition), developed by CDP and the French environment and energy agency ADEME, also considers future outlook of indicators as key. This is not enough, and we should encourage companies to design their accounting to strategically consider long-term value creation. We made a few proposals to combine management control fur sustainability with long-term thinking in a 2018 article.

Little did we know that 'value' would be turned around by a spreading virus

While different companies have accounted for between three and six capitals to date, the Covid-19 crisis has put the light on four that will need increased attention from organisations and standards-setters alike. First, intellectual capital. Very few companies report on it (fewer than 50%, according to a 2019 report on worldwide integrated reports), while the crisis has demonstrated that R&D, culture, information systems and the like play a strategic role in the ability of organisations to reorganise in times of crisis and scale up answers for new products (for example in the development of an open-source respirator from a unique collective work in France, the project MakAir).

Second, social capital has proven key in being able to locally reorganise supply and demand networks. Companies’ social immune system is key today and will be key tomorrow. Third, biodiversity was put in the spotlight through the link made by several researchers between deforestation and the increase risk of zoonosis (See 'There's no longer any excuse to source from recently deforested land'). Finally, the face of human capital has changed. From publishing the number of managers, companies will have to rethink who their “valuable” employees are. We have all applauded our health professionals, and many more people, such as supermarket cashiers. Little did we know,that “value” would be turned around by a spreading virus.

Few reports today allude to planetary boundaries, let alone apply them in multi-capital accounting. Two examples are the Olam integrated impact statement, which has been published for the last two years, and the Tourism Holdings Limited report, which uses the Future Fit Framework. A good way to start with this new accounting would be to look at Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model.

The MultiCapital scorecard, developed by McElroy and Thomas in 2016, has just released an open-source version to implement the doughnut.

The city of Amsterdam is using it to design its future strategy post-Covid19, while France used it to report on its sustainable development last year, allowing the country to take a look at the interactions between human needs and overall respect for the environment.

“System value can only be created when the outcomes of a business model maintain capital stocks and flows within the thresholds of their carrying capacities,” according to r3.0, a global common good not-for-profit platform, which published a number of open access blueprints to help develop a new economy and society:

To build, drive and implement this new accounting, we need new accountants. Hybrid accountants with the capacity to see 360° and not just 60°. We need a new education system for accountants, new roles as well, such as the hief value officer, described in the eponymous 2016 book by Mervyn King and Jill Atkins.

This is the only way that we will raise to a new standard of governance of our organisations and stewardship of our commons. Let’s step up and raise to the challenge.

Delphine Gibassier is associate professor of Accounting for Sustainable Development at Audencia business school in France

This commentary is part of our in-depth briefing Building back better: Ethical Corporation examines what Covid-19 will mean for sustainability

Covid-19 natural captial Kate Raworth doughnut economics Value Balancing Alliance Rotman School of Management TFCD ACT Framework MakAir Olam MultiCapital Scorecard