California's floating wind lead threatened by fast-rising Maine

California is likely to miss its 2030 floating wind target due to supply and grid risks while pragmatic investments and state legislation are boosting Maine's outlook.

Related Articles

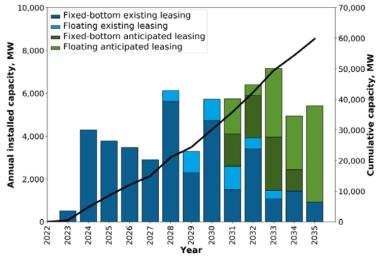

The U.S. has allocated its first floating wind leases and aims to install 15 GW by 2035 but participants warn the first large-scale arrays may still be a decade away.

Development activity is growing on East and West coasts but transmission grids, ports and supply chains must be expanded to achieve commercially viable projects.

California and the East coast state of Maine have set out floating wind targets but different strategies towards the scaling up of floating wind could see their trajectories diverge.

In the U.S.’ first floating wind auction, the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) allocated five floating wind projects in California for a total 4.6 GW capacity.

The state of California aims to install 2 to 5 GW of floating wind capacity by 2030 and 25 GW by 2045 but market observers do not expect the first projects to come online before 2035.

The deep waters of the Pacific Coast mean that, unlike on the East Coast, developers will not benefit from infrastructure built earlier for conventional fixed-bottom offshore projects. Ports must be expanded and adapted to assemble huge components and regional supply chains must be built out to achieve economies of scale.

“We’re building a whole new industry," Adam Stern, Executive Director at industry group Offshore Wind California, said.

Forecast US offshore wind installations

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: Department of Energy report on U.S. offshore wind supply chain, June 2022

Significant investments in ports and transmission upgrades will be required to install large commercial arrays and California is yet to establish a mechanism to procure power at scale, Stern said.

Other key measures include "setting a clear permitting roadmap, building a robust supply chain and workforce training,” he said.

In Maine, a more deliberate approach to power offtake contracts, transmission and scaling up of floating wind technology could see it overtake California and lead early U.S. floating wind deployment.

The state of Maine plans to install commercial-scale floating wind by 2032 and Maine Governor Janet Mills has signed into law a bill to procure 3 GW of floating wind by 2040 through long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs).

An auction for commercial leases in the Gulf of Maine, including Maine, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, is expected next year.

Listening to locals

Offshore wind projects can face strong opposition from local industries or citizens, most notably the fishing industry.

Developers and state authorities must engage with local stakeholders early in the phase to mitigate the risks. Lease allocations in California came after several years of dialogue between developers and local associations.

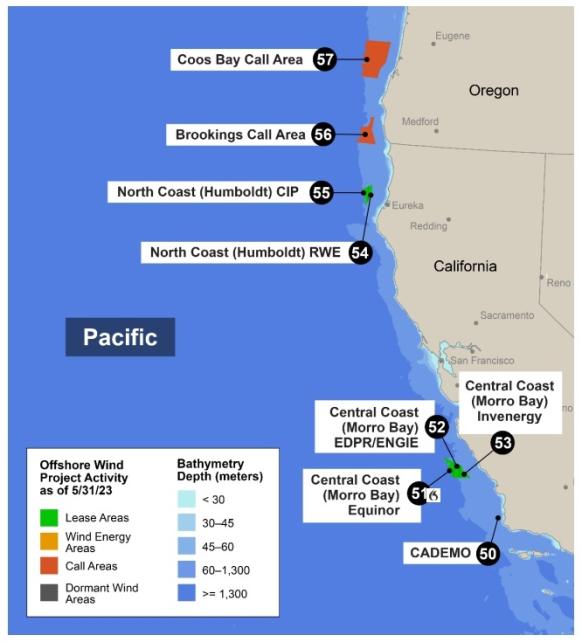

Offshore wind projects in US Pacific

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: Department of Energy's 2023 Offshore Wind Market Report.

Last month, a number of groups contested a proposal by BOEM for two floating wind areas off the coast of Oregon that could host 2.6 GW of capacity.

In one example, the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians said the projects were premature and a threat to “fisheries, local fishing jobs, and some of Oregon’s pristine ocean [views].”

The opposition results from a lack of dialogue between federal authorities and local parties, Alla Weinstein, CEO of developer Trident Winds, told Reuters Events.

Trident Winds was an early mover in California, developing an unsolicited project in Morro Bay California before BOEM allocated three leases in the area. The company is now developing an unsolicited project in Washington State, where a 2019 Clean Energy Transmission Act (CETA) requires electric utilities to be carbon neutral by 2030 and generate 100% of electricity from zero carbon sources by 2045.

“There is one major difference between the process that gets initiated by a developer versus the process that gets initiated by the federal government, and that’s stakeholder relations,” Weinstein said.

Trident's development work in California established relationships with the local community which helped "get people onboard ahead of the [lease] auction," she said.

Proving concepts

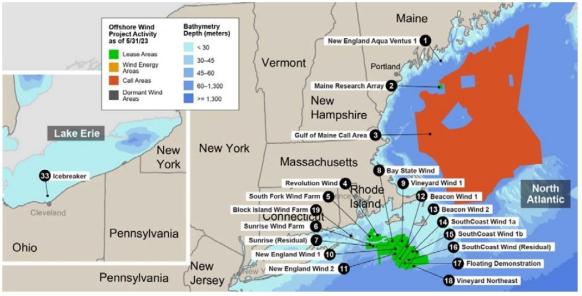

On the East Coast, the state of Maine is looking to build a demonstration floating wind farm before larger arrays.

In May, the BOEM started an environmental assessment of the 144 MW Maine Research Array (MeRA) floating wind project being developed by Aqua Ventus, a partnership between Mitsubishi subsidiary Diamond Offshore Wind and German energy group RWE alongside state partners.

The project uses a structure developed by the University of Maine and the partners plan to install a pilot floating wind turbine of capacity 11 MW by around 2026, followed by the ten-turbine MeRA array by 2030-2031.

Offshore wind projects in US North Atlantic

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: Department of Energy's 2023 Offshore Wind Market Report.

The projects will test the ability of floating wind farms to co-exist with local fisheries and provide valuable data to commercial developers planning to build larger arrays. The Maine Lobstermen’s Association (MLA) has said the federal authorities were moving too fast in developing offshore wind in the Gulf of Maine and other parts of the East Coast.

Maine is taking a "deliberate" approach to scaling up floating wind, said Professor Habib Dagher, executive director at the University of Maine.

"We often call it the 1, 10, 100 plan. It includes putting a single turbine in the water first, then 10 turbines, then doing commercial scale with 100 turbines or more,” Dagher said.

In July, RWE said it would sell its shares in Aqua Ventus to Mitsubishi after gaining "valuable knowledge for commercial scale leasing opportunities in the Gulf of Maine."

Grid gaps

Grid constraints are another major issue for developers in California. BOEM allocated two leases in Humboldt Bay in Northern California and these will require significant onshore grid expansions to transport the power south. The three leases allocated near Morro Bay in central California should benefit from grid capacity made available following the closure of the 2.2 GW Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in 2029-2030, but further transmission work will be required.

In contrast, the Gulf of Maine Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force is studying transmission needs alongside environmental and research concerns in pre-leasing discussions with the BOEM. The task force represents Maine, Massachusetts and New Hampshire and areas of discussion include possible landing points, how transmission is factored into the leasing process and requirements for onshore grid upgrades.

Last year, consultancy DNV set out potential transmission strategies for Maine in a technical study commissioned by the state.

Elsewhere on the East Coast, the state of New Jersey was the first to use a new holistic grid planning process created by regional grid operator PJM that reduces costs and transfers responsibility to power authorities. PJM sets out transmission investments required to meet state renewable energy targets which are then approved by state authorities.

The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) has asked California grid operator CAISO to evaluate the transmission costs for connecting large amounts of offshore wind in central and northern areas.

In May, CAISO agreed to build upfront bulk transmission that will support onshore wind, solar and storage projects and the American Clean Power association (ACP) is urging the grid operator to set out upgrades required for offshore wind in its next multi-year investment plan expected next year.

Reporting by Juliana Ennes

Editing by Robin Sayles