US solar builders chasing American cells, factory plans show

Announcements of capital-intensive cell factories have surged as developers seek bonus tax credits and less global risks but, for now, most of the silicon wafers used in cells will come from Asia.

Related Articles

A year since President Biden's Inflation Reduction Act, solar suppliers and developers are pushing ahead with new manufacturing facilities that will transform supply dynamics.

At least 52 projects to expand solar manufacturing facilities were announced by the end of July, comprising 62 GW/year of new module capacity (up from 7 GW at present), 35 GW of cells (up from 3 GW), 10 GW of wafers/ingots (0 GW previously) and 29 GW polysilicon (up from 22 GW), according to figures from the American Clean Power (ACP) association. Essentially, silicon is sliced into wafers that are used to build cells, which are then assembled into modules.

U.S. solar installations must triple to over 60 GW/year from the middle of the decade to achieve President’s Biden’s climate goals. Domestic module production capacity represented only one third of annual solar installations at the end of 2022, making most developers dependent on imports from Asia.

To reduce this dependence, the inflation act offers solar and wind developers a 10% tax credit for using U.S.-made content, on top of a 30% baseline tax credit.

For the first time, solar developers are investing in new U.S. manufacturing facilities to secure the tax credits and reduce the risk of trade tariffs and global supply chain issues that have pushed up prices and delayed projects.

Projects must source over 40% of the cost of modules, trackers and inverters from the U.S. to gain the domestic content bonus, under guidelines set out by the Treasury Department in May.

Module factory plans are outstripping cell and wafer production as these typically assemble ready-made cells and other components and the facilities can be permitted and operational "within six to 12 months of the investment decision," Tom Starrs, Vice President Government and Public Affairs at developer EDP Renewables North America, told Reuters Events.

“Cell fabrication involves more chemical processing and a more specialized workforce, so the siting, permitting, and logistics are all more complicated," he said.

Still, significant plans for U.S. cell factories show that project partners are seeking domestic cells to gain the content bonus. Meanwhile, most will depend on imported wafers.

“Given the current status of the supply chain and the general cost breakdown among the components for modules, it is generally believed that only those modules with U.S. domestically manufactured cells can truly have a shot at complying with the 40% or higher value requirement,” Xu Chen, Senior Director, Power, Renewables & Energy Transition at FTI Consulting, said.

Modules first

By procuring U.S. components, developers can avoid supply risks that have been exacerbated by trade tariff uncertainty and soaring global demand for solar power.

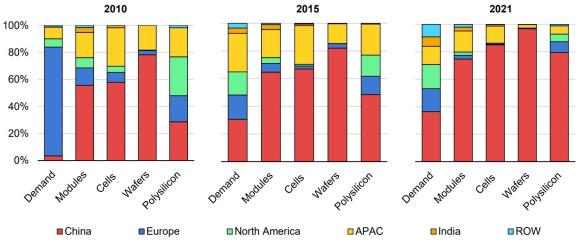

Solar manufacturing capacity by country, region

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: International Energy Agency's Report on Solar PV Global Supply Chains, August 2022

Last year, many projects were delayed by a ban on projects made from forced labour in China’s Xinjiang Province that led to lengthy module seizures at the U.S. border as customs officials checked documents. The Xinjiang region produced almost half of all global polysilicon output in 2021, according to U.S. Department of Labor estimates. Other U.S. projects were delayed due to volatile costs, logistics issues and uncertainty over import tariffs.

Solar power purchase agreement (PPA) prices fell in the second quarter of this year, representing the first fall in prices since 2020 and indicating global costs were stabilising and developers were starting to incorporate benefits from the inflation act, pricing platform LevelTen Energy said.

Large U.S. module factories are now under construction. Renewable energy developer Invenergy is building the U.S.' largest solar module factory in Ohio with Chinese partner Longi. The 5 GW/year Illuminate USA facility will supply monofacial and bifacial solar modules to the utility-scale and rooftop solar markets and Invenergy will purchase 40% of all output, a company spokesperson told Reuters Events in April.

South Korea supplier Hanwha Qcells plans to invest $2.5 billion in a factory in Georgia that will take its U.S. module production capacity up to 8.4 GW/year by 2024. Renewable energy developer Enel plans to build a 3 GW/year cell and module manufacturing project in Oklahoma next year, but most new facilities will be stand-alone rather than vertically integrated.

Supply chain

Vertically integrated factories can reduce transport costs and risks but the overall benefits will depend on component sourcing, regional costs and the business model of the facility.

The capital cost of wafer and cell manufacturing in the U.S. is three to five times higher than in China or Southeast Asia, Chen said, based on conversations with manufacturers.

U.S. manufacturers face higher equipment and construction costs while chemical processes require additional environmental permits and trade tariffs mean companies face uncertainty over what kind of polysilicon and wafers can be imported into the U.S. “trouble-free,” he said.

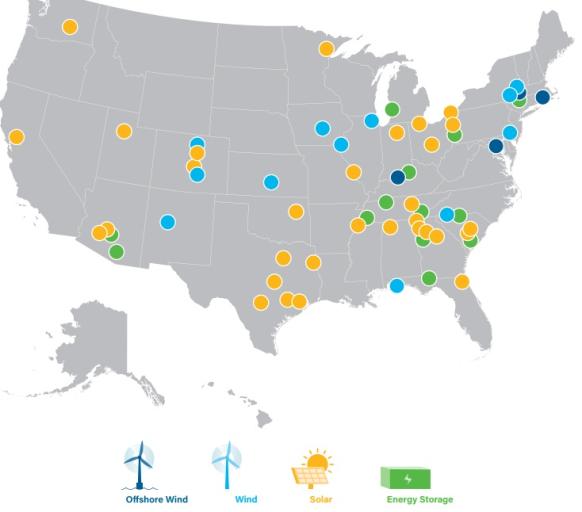

US manufacturing announcements since inflation act

(Click image to enlarge)

Note: location of 14 other new facilities yet to be announced.

Source: American Clean Power, August 2023

Announcements in new U.S. polysilicon and wafer production have been encouraging but limited in scope, showing more hesitancy by some suppliers on the value of upstream activities. In July, the Department of Energy (DOE) said it would fund up to 12 projects to manufacture polysilicon, wafers or cells through a separate incubator funding plan.

Meanwhile, a surge in U.S. module production could actually see domestic supply outstrip demand by the end of 2025, Chen said.

Solar installation rates should then catch up as developers secure inflation act incentives and more projects enter construction, he said.

Sustained competition

Even with tax credits, U.S. manufacturers will need to maximise their competitiveness to maintain a foothold domestically.

Asian suppliers benefit from lower labour and building costs and larger factories that gain economies of scale. Chinese factories developed by companies such as JinkoSolar, Tongwei Solar and Trina Solar average more than 10 GW/year, far larger than the planned U.S. facilities, according to BMI Research, a subsidiary of Fitch Ratings group.

The U.S. has imposed tariffs on a group of companies importing panels from the four largest supplier countries of Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, but the Biden administration has waived these tariffs until mid-2024 to support U.S. solar development while domestic manufacturing is ramped up. The suppliers circumvented tariffs on goods produced in China by using Chinese made wafers in factories located in the Southeast Asian countries, U.S. federal authorities said.

Going forward, Biden's waiver gives the suppliers time to source wafers outside of China, which will allow them to supply the U.S. tariff free.

This would make imports from Asia more competitive, but BMI analyst Christopher Colacello predicts the reduced supply chain risks and tax incentives for domestic components “will outweigh the low costs of cells procured from Asia.”

Reporting by Neil Ford

Editing by Robin Sayles