LTOs, SMR deployment hang on building out supply chains

It is essential to strengthen and expand supply chains for the coming deployment of advanced nuclear reactors and for lifetime extensions, say those in the industry.

Related Articles

In 2022, post-pandemic inflation, soaring gas prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and ongoing push for lower carbon emissions has helped nuclear power stage something of a comeback in public opinion, but years of low growth and technological inertia means feeding the industry new parts and new people could be its greatest challenge.

“We’re in the realms of a nuclear renaissance. While that’s been promised numerous times, it’s slowly being delivered and activities in Eastern Europe have driven a lot of people to reconsider,” says Chair of the International Nuclear Utilities Obsolescence Group (INUOG) John Latimer.

“Over the last 20 years there’s been huge changes in the nuclear industry, a lot of consolidation of suppliers, both in the United States and worldwide, and generally few new players entering the market.”

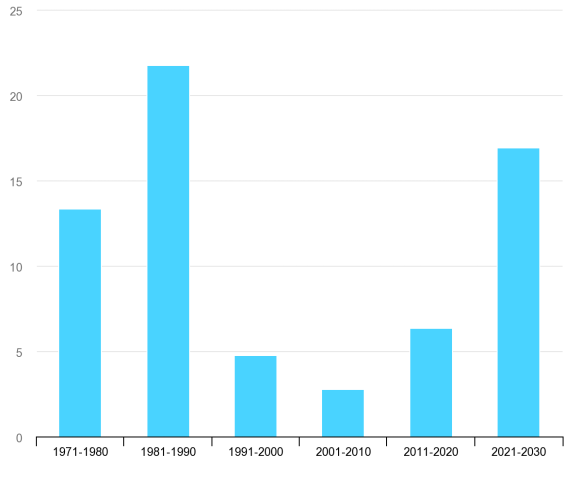

Global nuclear power capacity additions in the Net Zero Scenario, 1971-2030

(Click to enlarge)

Source: International Energy Agency (IEA)

Existing infrastructure

The turning tide toward nuclear as a low-carbon solution alongside renewables such as solar and wind is being welcomed by those in the industry, but an increased focus on refurbishing old plants for long-term operation (LTO) and bringing in the new generation of reactors has many concerned that the support infrastructure is not up to the challenge.

Low demand from existing operators means many suppliers have drifted away to find more lucrative revenue streams, Latimer says.

“We recognize that, if we don’t order parts and we allow the supply chain to dwindle, why would we expect a supplier to be waiting multiple years for us to turn up and ask them to provide us with an item?”

SMRs, especially, have piqued operators’ imaginations and demand for the new technologies, many of which are expected to be commercially available by the end of the decade, has come from non-nuclear countries and even U.S. states that previously had a moratorium on nuclear power, says vice president of the Clinch River Project for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) Greg Boerschig.

Existing nuclear will need to be built upon first, he says.

“The success path will be first in countries with well-developed industrial base, the infrastructure to support a robust supply chain, and the capacity to draw the expertise to assemble a regulatory framework,” Boerschig said during a Reuters Events webinar ‘New to the Game – A Global Growth Perspective of SMR Deployment Progress.’

“That’s where it will start. It will grow beyond that, but it’s a very complex industry and you need those foundational aspects to start.”

Energy security problems unearthed by the Ukraine war are not hitting all countries equally, he said, but there has been a knock-on effect across the globe.

“Where (energy insecurity) touches everybody is in the development of the supply chain. That’s touching everything and every aspect of design and construction and everything we’re doing is really predicated on having a reliable supply chain,” he says.

“In North America, there are very few vendors and capacity is an issue and there’s a lot of interest in SMRs in (the United States and Canada). So, if everyone is going to be putting an order in for significant equipment, we’re going to be challenged.”

Human capital

The problem is not only shortage of parts but also skilled labor, according to Heather McKnight from the Advanced Reactor Development team at the Canadian utility NB Power.

“When it comes to deployment, having enough people in the pipeline is going to be a huge challenge,” McKnight said during the Reuters Events webinar.

“There’s a recognition that there’s only so much knowledge base and manpower out there, so everyone has to come together and collaborate to ensure that we have that knowledge base, that experience,” she said.

Direct employment for a single unit 1 GW advanced light water reactor during site preparation and construction at any point in time for 10 years is around 1,200 professional and construction staff, or about 12,000 labor years, according to a joint study by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Total direct employment in the nuclear power sector of a given national economy is therefore roughly 200,000 labor years over the lifecycle of a gigawatt of nuclear generating capacity, the report says, noting that this number doesn’t include the hundreds of thousands of secondary jobs associated with any given nuclear project.

Joint effort

The key, says INUOG’s Latimer, is keeping communication open with the active suppliers in the industry and building on what the nuclear industry has already achieved.

“There’s a very good interchange at international forums, whether its INUOG or NUOG with some of the key suppliers that are very active in the field, and they say if you don’t tell us the demand and don’t give us some forward indication, we don’t know whether to keep some lines open,” he says.

“We try to keep our top 100 suppliers openly communicated with, so even if they don’t have any orders this year … there’s an expectation that the supply chain team will keep in contact with them to say what the forward position is.”

One problem, he notes, is that while some parts, such as electric relays, are used in many other industries, nuclear operators would order dozens of pieces, while another industry would be ordering thousands, leaving nuclear a very small part of the supplier’s investment and development program.

For the moment, the nuclear community works closely together to find parts, regardless of competitor lines.

During a recent INUOG call, Argentine operators asked about the availability of seismically qualified anchors for plants constructed in earthquake-prone regions after their previous operators in the U.S. stopped supplying them and parts from their Chinese supplier failed the specification tests.

“There were four utilities immediately interested in feedback and options and ideas from around the table. So, one little question sparked an international chain of help and for me, having worked in other industries than nuclear, that’s unheard of,” says Latimer.

A nuclear safety concern in one part of the world has ripple effects across the industry, and that helps foster a joint effort to effectively solve supply problems.

“The nuclear industry has the ethos that we are there to protect nuclear safety and the primary goal is to make sure plants are reliable and safe as possible,” he says.

By Paul Day