Mark Hillsdon reports on how the idea of increasing the capacity of soil to absorb CO2 is gaining traction around the world, promoted by organisations including the Food and Land Use Coalition, the 4 per 1000 Initiative, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development

In 2015, the International Year of Soils, Maria Helena Semedo, a deputy director at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, famously commented that the world’s topsoil had become so degraded that it could only support another 60 harvests.

Decades of deforestation, monoculture, and poor farming practices, often over-reliant on chemical inputs, had stripped the land of all its goodness. It’s estimated that 75 billion tonnes of fertile soil are lost to land degradation every year, leaving Earth, which is still expected to feed an ever-growing global population, in a parlous state. Last month, the FAO warned that more than than 90% of all the Earth's soils could be degraded by 2050 if we continued on the same path.

At Ethical Corporation Responsible Business Summit in New York in March, Satya Tripathi, assistant secretary-general at UN Environment, said that by over-using fertiliser: “We jettisoned soil biology and focused on soil chemistry … [and] completely destroyed the soil ecosystem, so that in most parts of the world, we hardly grow anything.”

We can change agriculture from being one of the major contributors to climate change to becoming one of the major solutions

Last year, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) launched The Business Case for Investing in Soil Health, a report that included a call to action for businesses to explore greater supply chain co-operation, public-private partnerships and landscape alliances that could help spread costs and risks of land remediation.

There is also a greater realisation that as well as playing a central role in food security, healthy soil can also help in the fight against climate change. The Earth is a huge carbon sink, with soil holding three times more carbon than the atmosphere, but this carbon is now being allowed to escape.

Nevertheless, André Leu, a director of Regeneration International, believes that by taking a few fairly simply steps not only can we keep this carbon locked underground, but we can add to it, too. “We can change agriculture from being one of the major contributors to climate change to becoming one of the major solutions,” he says.

This idea of soil as something that could sequester carbon dioxide began to gain traction at the Paris Summit in 2015, when scientists explained that if we could change agriculture so that farms are actually increasing the amount of carbon in the soil, by four parts to every 1000, that would be the equivalent of locking up all man-made greenhouse gas emissions. This became the 4 per 1000 initiative, which is now backed by 35 countries and over 1000 organisations.

In their current state, the world’s soils are far from being a solution to global warming. But regenerative, or restorative, agriculture can change this, by encouraging farmers to adopt a mixture of techniques that improve soil health and promote plant growth.

No tilling, and a lack of soil disturbance, is one way of keeping carbon in the soil, while cover cropping, which helps prevent soil erosion, crop rotation and tree planting, are also used. “These are the kinds of practices that keep carbon in the soil, underground, and out of the atmosphere,” says Daniella Malin, deputy general manager of the Cool Farm Alliance (CFA), a partnership of retailers, manufacturers and NGOs. “[But] the core of regenerative agriculture is soil and organic matter… that’s the foundation of everything.”

We can increase yields, lower production costs and, really importantly, increase resilience to the adverse effects of climate change

Many NGOs are now running composting workshops for smallholders, showing them how they can turn farm residues, which would often have been burnt, into something they can dig into the soil to replenish its nutrients. The CFA has been working with coffee farmers on different ways of managing waste too, and has developed new methods of turning pulp from coffee production into a rich, natural fertiliser.

CFA is also behind the Cool Farm Tool, a greenhouse gas calculator that can measure carbon production from the use of fertilisers and fossil fuels, but also estimate the amount of carbon that the land and crops are sequestrating, to provide a net carbon figure.

Large agribusinesses such as PepsiCo, Danone and Unilever have used the tool to meet their corporate commitments, and from next year they will be able to further measure their progress with the launch of a new Science Based Targets Network. This will allow companies and cities to set targets for the inter-related systems of land, biodiversity, freshwater and the oceans across their value chains.

Smallholders are also applying the CFA tool as a way of monetarising their sustainable practices, with climate-friendly farming often a way of gaining easier access to finance and loans. Leu believes it is critical that regenerative agriculture is made as attractive and hassle-free as possible for farmers. “What we want to show is that these systems do make farms more profitable,” he explains. “We can increase yields, lower production costs and, really importantly, increase resilience to the adverse effects of climate change.”

Among the businesses Regeneration International works with are health firm Mercola and clothing company Patagonia, corporations which Leu says are actively promoting regenerative agriculture, as well as sourcing materials from regenerative systems. “At the end of the day, landowners or farmers have to make a living,” he explains, “and if we can set up market-based systems that can help farmers earn a good living while they’re regenerating their farms and landscapes, that will make a big difference.

According to Jeremy Oppenheim, a principal at the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU), the support of agribusiness is one of three fundamental ways of creating the incentives that are needed to encourage more long-term investment into regenerative agriculture.

There's a huge opportunity not to spend more, but spend better

The first, he says, is for food companies to enter into long-term agreements with farmers to reduce chemical loading and increase regeneration in the soil. It's already happening in places, he adds, with the likes of Danone, and some of the cocoa companies, “entering into long-term contacts precisely to achieve these outcomes,” and to give farmers a greater degree of financial stability.

In the same way, he says, banks could provide lower cost credit to farmers that use the right practices. “It's not just a piece of corporate social responsibility, it's brilliant banking,” he says, “because ultimately they see those farmers as lower risk.” It’s an approach that is working in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (see Innovative BNP Paribas loan helping 6 million Indian farmers go chemical-free)

The third area is subsidies. FOLU estimates that around 80% of the $500bn spent on agricultural subsidies each year goes to the wrong people. As well as ending up in the pockets of agribusinesses, rather than farmers, Oppenheim says, “a lot of the subsidies are effectively linked to production, so the more you produce, the more subsidy you get.” In some parts of the world the subsidy regime is also connected to inputs, when farmers are paid to use more fertiliser and pesticides. “So there's a huge opportunity not to spend more, but spend better,” says Oppenheim.

Partnerships are a key element to all these ideas. In Colombia, FOLU is working with local stakeholders, the private sector and a range of government ministries to reduce the use of harmful agrochemicals, which have been damaging the health of people and the land. The initiative includes returning to traditional practices and using naturally derived inputs, and has won the support of several private firms. Fertiliser company Yara International is now providing extension services to farmers who employ sustainable practices, for instance, (see Yara's mission to sow hope in Africa) while biosolutions firm EcoFlora is supporting them with the use of bio-inputs.

The project is also helping Colombian farmers to tap into international markets that put a greater emphasis on food safety standards, deforestation commitments and the growing consumer demand for responsibly sourced produce.

In September, at the UN Secretary-General’s Climate Action Summit, FOLU is launching a major report that sets out the economic case for the transformation of food and land use systems. It will focus on the political and economic opportunities of shifting food and land-use from being a major contributor to climate change and inequality, into a source of balanced economic growth, human health and a flourishing natural environment.

What we are talking about is the transformation of the old system, which has brought us a lot but is now killing the planet

Commonland is another key player in landscape regeneration. The not-for-profit was set up by Willem Ferwerda after he realised that while a thousand hectares could be preserved by a local NGO, around it were a million hectares that had been converted from rainforest to palm oil.

Commonland’s approach combines and connects natural and economic landscape zones, he explains. “What we are talking about is the transformation of the old system, which has brought us a lot but is now killing the planet.”

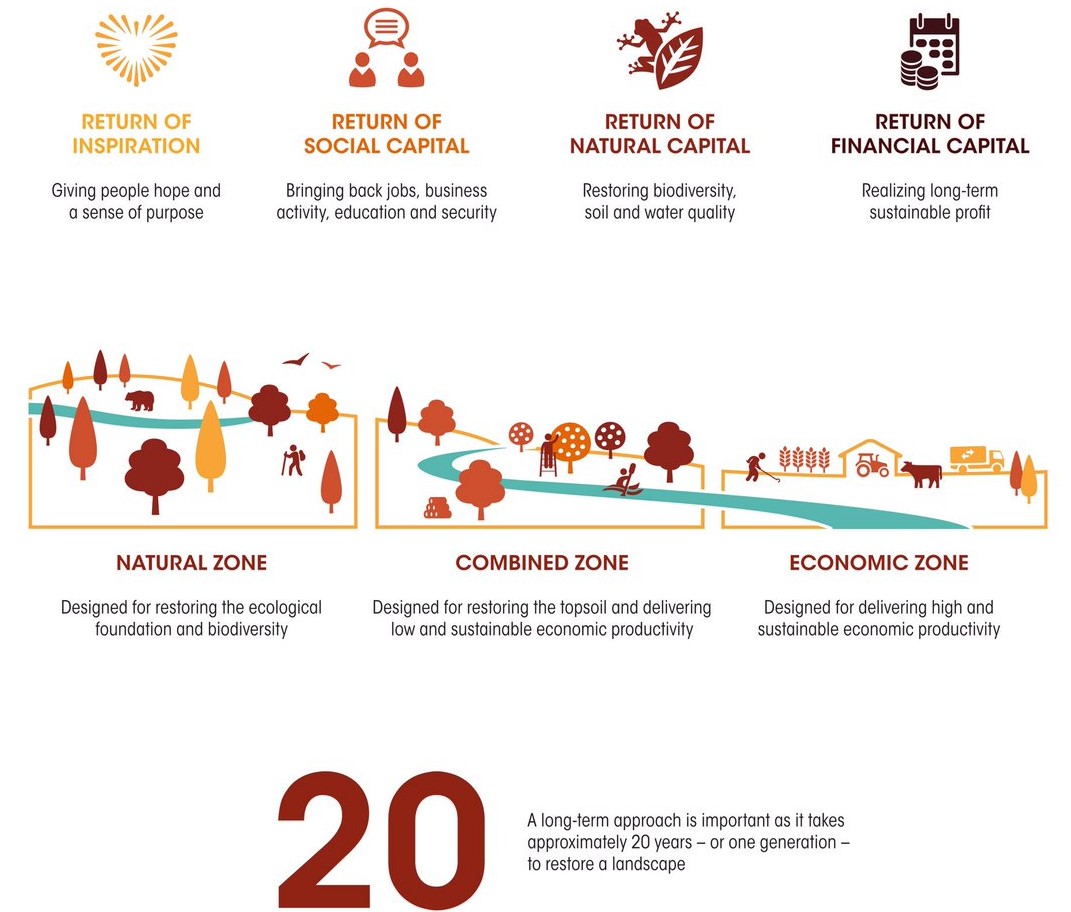

The system is based on four returns, three landscape zones, and 20 years, which is the amount of time it takes to restore a degraded landscape, he explains.

People and community play a key role in Ferweda’s vision, so the returns include inspiration, which gives people hope and a sense of purpose; social capital; natural capital, such as biodiversity and soil quality; and financial capital, which is sustainable and long term.

To realise this, he continues, three different landscape zones need to be established, each with a different emphasis. On the one hand is the natural zone, where investment is aimed at restoring nature and biodiversity, in return for forestry and tourism. At the other end is the economic zone, where there is an acceptance of real estate and agriculture, in return for crops and economic development. In the middle is a combined zone, a buffer, where restoring the landscape would be important, alongside agroforestry and orchards. Importantly, all three zones would be actively involved in absorbing carbon.

Commonland works in some of the most climate-stressed areas in the world, including the Mediterranean, South Africa and Australia, where they look to breathe new life into degraded landscapes.

Ferwerda certainly doesn’t lack ambition and, working with Wide Open Agriculture, he has plans to transform the Western Australian wheat belt, a vast arid landscape of abandoned towns, degraded soils and an ecosystem in crisis, into a new sustainable food belt.

There are multiple techniques farmers can choose from … but it can be done without having to make any major modifications to farms or equipment

Ideas for achieving this include farming practices based on innovative water management, measures to restore the soil and biodiversity, huge greenhouses to allow for the growth of fruit and vegetables, and plans to encourage immigrants – the “new Australians” – to move to the area and re-establish businesses, farms and whole communities. There are also plans to scale-up and encourage investment by listing on the Australian Stock Exchange.

Ferwerda is confident the finance is there, too. Having spoken to a number of investors, he discovered that many were searching for sustainable projects where their long-term investment could make a difference, but until now there simply wasn’t a pipeline of initiatives to support.

Commonland is also working in South Africa, in partnerships with NGOs, local farmers, businesses, and government, to bring back life to 500,000 hectares of land around Port Elizabeth. Among the initiatives launched to restore this important food production area is a move away from traditional goat farming to more sustainable, profitable farming practices, and a partnership with a major corporate to reforest the area.

Elsewhere, dozens of other NGOs are forging partnerships with the private sector to revitalise degraded land. In Kenya, the Drylands Natural Resource Centre (DNRC) works with over 600 smallholders on agricultural and agroforestry best practice, and has so far planted over 100,000 new trees. In the central Africa state of Niger, farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) has revived more than 200 million trees across 5 million hectares using simple techniques to regrow trees and shrubs, and integrate them back into farming systems to improve soils.

What links so many of these projects is that they involve re-introducing simple, often traditional farming techniques. “This is the other wonderful thing about it,” says Leu. “There are multiple techniques that farmers can pick and choose from… (but) it can be done without having to make any major modifications to their farms or equipment.

“This is resonating with farmers because it is so doable, it makes sense, it's achievable.”

Mark Hillsdon is a Manchester-based freelance writer who writes on business and sustainability for Ethical Corporation, The Guardian, and a range of nature-based titles including CountryFile and BBC Wildlife.

This article is part of the in-depth briefing Climate-smart agriculture. See also:

Securing the future of food on a planet in peril

Innovative BNP Paribas loan helping 6 million Indian farmers go chemical-free

The American farmers who are ploughing a regenerative new furrow

Dutch farmers plot a greener revolution by sowing biodiversity

How Syngenta’s regenerative approach is helping Spanish olive groves to flourish

Yara’s mission to sow hope in Africa

Growing fears for climate help fuel rise in plant-based diets

New hope for solutions to deforestation in the Cerrado

Why business holds the key to a healthy, fair and sustainable food system

How investors can catalyse a blue revolution to save marine ecosystems