Can a company or group of companies create systemic change in the supply chain? Yes – but only with enough collaboration and commitment

When Human Rights Watch published a damning report into labour abuses in the Kazakhstan tobacco fields supplying Philip Morris International (PMI), the company’s chief executive “took it personally”. This, says Robin Jaffin of US based NGO Verité, was the key to a radical and ongoing reform of the Swiss company’s supply chain that has gone far beyond public relations.

Back in 2010, the publicity was certainly all negative. Human Rights Watch, which had interviewed migrant Kyrgyz workers, said children as young as 10 were working on the harvest and some families were forced to toil for eight or nine months before getting paid. In many cases those who wanted to leave could not, because their employer withheld their passports. Additional criticisms were also made over lack of safety.

However, by November 2013 the US Department of Labor had removed Kazakhstan origin tobacco from the “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor”.

So, what happened in the interim? In short, a strategic, consultative partnership with Verité that generated PMI’s Agriculture Labor Practices (ALP) programme in 2011. PMI had already worked with Verité on outreach programmes for tackling green tobacco sickness – a form of nicotine poisoning caused by contact with wet plants – and assessment of a child education scheme in Argentina. But the Kazakhstan case had a more dramatic impact.

ALP’s goal is to progressively eliminate child labour and other labour abuses and to achieve fair and safe working conditions on all the 490,000 or so farms in more than 30 countries where PMI sources tobacco. Most of these are small-scale enterprises of two hectares or less. While PMI and Verité both admit there is plenty more to be done, including in tobacco producing countries in the developed world, such as the US, they point to success in communicating the ALP code to all these farms as well as building a full picture of who lives and works on each farm.

Training of employees, suppliers and growers has already been extensive and PMI has committed all suppliers and affiliates to prompt action in the worst cases of child labour, abuse and hazard. Transparency is also key. PMI has pledged to full disclosure of third party assessment reports to stakeholders.

“A lot has to do with the level of commitment and resources that PMI put in,” says Jaffin, Verité’s director of supplier programmes. “Once they decided to do it, they have kept it as a priority.

“Also, they decided this was going to be an area of non-competition, so PMI are sharing all findings and materials with other companies. The tobacco processors Universal and Alliance One, for example, have not only adopted all PMI’s standards and approaches but also rolled them out to all growers beyond PMI’s suppliers. The impact is an “alignment around expectations” among an increasing number of tobacco growers, Jaffin says.

But the process is not one-size-fit-all. “For any kind of long-term systemic change you need cooperation with workers, civil society, government and so on,” says Jaffin. “You will see PMI participating at ECLT (Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing countries) roundtables with all kinds of stakeholders.”

Yet isn’t tobacco a questionable choice of where an NGO should target resources, given its harmful effects? On the contrary, Jaffin says, the workforce often desperately needs protection. “When you look at the tobacco smallholder supply chain, it’s one of the most vulnerable on the planet and they deserve a voice. We see the opportunity to establish progress within this massive supply chain.”

Lisa McCooey, communications planning manager based at PMI’s Switzerland headquarters, says the key to advancing ALP in the coming years will continue to be close monitoring and training so that farmers adopt better, safer practices. “Every market differs,” says McCooey. “With ALP you have very strict global principles but you have to be mindful of cultural differences. You also have to give suppliers the chance to mend their ways before you cut ties with them, otherwise you’re directly putting them in a spiral of poverty.”

That said, in the US, PMI has broken contracts with 20 suppliers that did not meet its ALP standards.

“In 2013 we invested more than $30m on improving labour conditions in our supply chain. We also published our second ALP progress report,” McCooey says. This details how, for instance, efforts in Indonesia have focused on training farmers on preventing green tobacco sickness through simple protective clothing and equipment, and how in the Philippines promoting the use of labour-saving and safer devices for harvesting is reducing the reliance on children.

PMI is also committed to building a system of direct contracts with farmers rather than middlemen in the old auction system. “ALP is also about making sure we can provide, with the help of NGOs, those critical infrastructure improvements such as schools or summer camps to ensure children are in a safe environment and can learn and develop during harvest season,” Says McCooey. This applies in Kazakhstan and other countries. The company also actively encourages diversity into food crops, McCooey says.

Linked issues

Benjamin Smith, senior officer for corporate social responsibility at the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the UN agency, says the companies that are making the biggest difference to eradicating child labour in their supply chains all recognise that it is usually linked with other “decent working deficits”: collective bargaining, freedom of association, fair wages and so on.

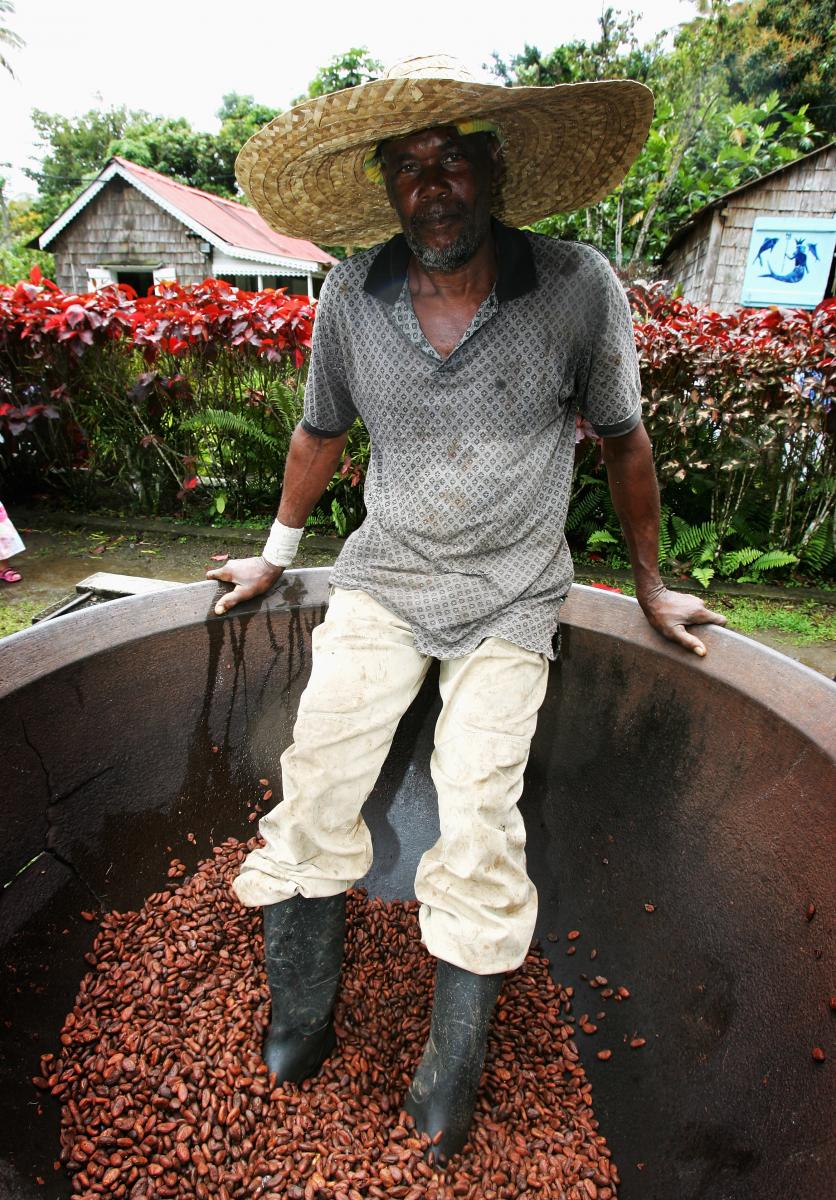

“We work extensively with Mars in the Ivory Coast, in their cocoa supply chain,” says Smith. “There they’ve very much linked sustainability efforts around improved agronomy, more efficient production, tackling diseases threatening the tree crop. They understand that their supply base is fragile and part of that stems from child labour and the rather bleak prospects facing young people in cocoa growing communities.”

Smith adds: “Those people are leaving, so the average age of farmers is something like 58. So it is in Mars’ interests to tackle child labour and make sure young people can be brought into the workforce under safe conditions above the minimum age. Mars have linked their sustainability programme with that rights agenda, in a good way.”

Another vital level of cooperation is between companies and governments, to reinforce the state’s capacity to provide education. Companies often understand the need for schools then go about trying to help in a “not very effective way”, Smith says. They build schools without making strong links with the ministry of education, resulting in lack of teachers. “Making sure those social investments are linked with commitment from government is very important,” Smith says.

But companies can support awareness-raising campaigns on the benefits of education and dangers of child labour, and they can also offer decent work opportunities. This shows they are not intent on prohibiting young people above minimum age from working, but want to enable them to do so under proper conditions where safety and schooling are not at risk.

One of the challenges is getting good data, Smith says. “Rigorous impact assessment is really worth the investment. Then companies can point to tangible progress on the percentage involved in child labour and revisit it a few years later. Global supply chains have an important role to play in demonstrating that good ethical production with respect for human rights and labour rights is completely compatible with competiveness and profitability, Smith says.

“With increasing attention being paid to these issues and how a well-treated labour force is capable of underpinning successful enterprises and businesses, that will have a knock-on effect and be very helpful in getting other firms and industries to replicate those practices.”

The ILO campaigns for industry-wide efforts. In tobacco and cocoa, particularly, the major companies that account for huge purchases are increasingly deferring to international standards on labour rights and the child labour conventions that are approaching UN ratification.

These stipulate a minimum age for light work of 13-15, as long as it does not threaten a child’s health and safety, or hinder their education or vocational orientation and training; a basic minimum age of 15 for work; and a minimum age of 18 for hazardous work (16 under strict conditions).

Today, 179 out of 185 ILO member states have ratified Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour, which include prostitution and trafficking. (However, the ILO estimates at least 38 million children worldwide aged 5 to 17 are engaged in some form of these.)

“The companies are also pushing those standards not just to their immediate business relationships where there’s a contractual obligation but looking further down the supply chain,” Smith says. By promoting these practices as far as possible, progressive companies are pushing the notion that such rights are precompetitive, a basic requirement for doing business in global markets.

In June 2014 the ILO also adopted a new legally binding protocol to strengthen global efforts against forced labour. It brings its existing convention on forced labour, adopted in 1930, into the modern era to address practices such as human trafficking. An accompanying recommendation provides guidance on implementation. An estimated 21 million people are in forced labour worldwide, according to the ILO, and about $150bn in illegal profits is made in the private economy each year through modern forms of slavery.

The protocol creates new obligations to prevent forced labour, to protect victims and to provide access to compensation for material and physical harm. It requires governments to take measures to better protect workers, in particular migrant labourers, from fraudulent and abusive recruitment practices, and emphasises the role of employers and workers in the fight against forced labour.

Other government intervention is also helping. For example, as of April 2014 India has a law requiring large and medium sized companies to contribute at least 2% of pre-tax profits to corporate social responsibility causes.

Another potential landmark in systemic change is Unilever’s enhanced partnership with Solidaridad, the international civil society organisation that facilitates the development of socially responsible and profitable supply chains.

In September 2014 the food and consumer goods giant signed a joint business development plan (JBDP) to improve the lives of 1 million people in Unilever’s extended supply chain by the end of 2017. The focus is on five main areas: agricultural practices, labour practices, gender equality, young agricultural entrepreneurs and land use management.

Dhaval Buch, chief procurement officer at Unilever, says the deal is about putting a formal structure to a relationship that has developed over several years, and taking it to the next level.

“We have been working with Solidaridad in Mexico, Vietnam, India, West Africa for some time but that’s been on an ad hoc, project-by-project basis,” says Buch. “What we want to do now is bring this into a joined-up plan.”

A logical extension to Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan, launched in 2010, the goal is to support sustainable production of primary feedstocks relevant to Unilever and to raise the number of farmers and workers who benefit via the supply chain.

Part of the plan

“This kind of focus is now part of our business plan, it’s not something on the side,” Buch says. “Whether it’s Manila, Tanzania or wherever, we realise we have to work in close co-operation with government, with local NGOs, all kinds of stakeholders.

“The issues we face involve so many elements from land use to scarce resources such as water. There is no doubt that we welcome similar action from other companies – it will require industry effort to make a real impact, no doubt about it.”

Nico Roozen, who started the Fairtrade movement 30 years ago and is now executive director of Solidaridad, says the plan covers economic, social and environmental aspects. “In our experience Unilever has been one of the first movers in sustainability issues and has turned out to be a committed partner on co-funding training programmes on tea, sugar, palm oil and other commodities. They have also given us insight and transparency into their supply chain.

“We have run many pilot schemes together in the last few years. Now we want to upscale them into the mainstream. About 150,000 farmers have been included in the last four years and we are confident we can reach 1 million.” Roozen describes the wider goal as turning sustainability “from niche to norm”.

If companies want assurance of supply of raw materials in the next 30 years, when they might have to double production to meet rising demand, then this can only be attained through sustainability, Roozen argues. Raising agricultural productivity in existing areas of production is another major plank of the joint policy, and Unilever and Solidaridad are also both calling for more government intervention where necessary.

A co-funding system of grants and private sector investment is crucial if these kinds of efforts are to be successfully scaled up, Roozen says. “A company like Unilever can help us not only co-fund but also introduce us to credit facilities, investment banks and innovative forms of funding,” he says. For example, enticing the processing industry to invest earlier in the chain – sugar mills close to the farmer, perhaps – could show those processors the benefits in higher yields that they have helped bring about.

Roozen cites Unilever and Mars among 10 first movers within the 125 companies with which Solidaridad engages. He says of the 10: “They are willing to make commitments to farmers and workers far beyond what is required by the certification agenda. I am confident these companies will be followed by many more in the near future.”

Does Smith of the ILO see a race to the top? “Certainly it’s a race to the international standards. Whether that’s the top or not, it’s where all enterprises should be starting from. Exceeding those is very welcome and there’s a strong moral case but also a business case to do so.”

Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan

Unilever has committed to sourcing 100% of agricultural raw materials sustainably by 2020; 50% by 2015.

It says 48% of agricultural raw materials were sustainably sourced by the end of 2013.

Unilever is concentrating on palm oil, paper and board, soy, sugar, tea, fruit and vegetables. It is on track with all except fruit and soy beans. “Working more closely with others will be essential in achieving broader change,” the company says.

Source: Unilever

Child labour Human rights labour practices PMI supply chain briefing systemic change tobacco

November 2014, London

Get answers to the latest issues and initiatives affecting your supply chain. Back for the 9th year, The Responsible Supply Chain Summit is the world's leading meeting place for senior executives looking to put sustainability at the heart of their supply chains