The economic cloud hanging over Italy could have a silver lining if companies modernise and embrace sustainability. But the opportunity for change might be limited

Italy can look like a triumph of style over substance. It is the world’s eighth largest economy, ahead of Russia and India, and as a manufacturing power ranks fifth or sixth globally, depending on which ranking you believe. Its companies produce premium brands that are desired worldwide, such as Bulgari, Prada and Ferrari. But something is not quite right.

Despite its apparent strength, the Italian economy has been bumping along a low-growth rut for more than two decades. Italy’s companies struggle to stay competitive, and productivity is lower than all countries of northern and western Europe (though ahead of countries such as Greece and Poland).

Wages are low, and there is an exodus of bright Italian graduates going abroad. There is also a brain drain within Italy, from south to north. The country is also crippled by public debt – in Europe only Greece is worse.

Italy’s main problem seems to be that nothing changes very quickly. Old attitudes persist and Italy’s many monopolies and vested interests, combined with a traditionally weak government, ensure stagnation. The government itself can fall into the hands of vested interests, as was the case under Silvio Berlusconi, for a long time Italy’s richest man.

Old families

The status quo benefits some. Apart from Berlusconi, the wealthiest Italians tend to be families that own long-established, now global companies, such as Michele Ferrero, Giorgio Armani, Miuccia Prada and the Benetton clan.

Overall, Italy is a country of obstacles for companies. These include “bureaucracy, labour laws and bargaining arrangements, tax, professional privileges, monopolies, mediocre education, and many more”, according to Bill Emmott, a former editor of the Economist and author of an article – Forward Italy: how to restart after Berlusconi – published in the Italian La Stampa newspaper in 2011.

Progressive business thinking on issues such as corporate responsibility and sustainability faces the same obstacles. Speaking to Ethical Corporation, Emmott says that corporate social responsibility in Italy “is quite good in terms of local community responsibilities, as the small family companies tend to be very rooted in their localities, and conscious of local pressures”.

He touches on some of Italy’s older problems. “It is not, however, as good on ethical behaviour – how could it be, in a country so rife with organised crime and corruption, in which the mafias have mutated from the old gangster image into a white-collar form? And there is very little environmental content.”

Signs of change

Italian companies compare poorly in corporate responsibility terms with their northern and western European counterparts. Neither the government nor campaign groups push them too hard, even though there are a number of issues that clearly need tackling, such as the relatively low participation of women in the workforce.

Italy’s high-profile international brand names tend to tick the corporate responsibility boxes in the same way as other multinationals, but even among some of the top brands, such as Dolce & Gabbana and Ducati, there is little responsible business activity.

But those that believe in corporate responsibility’s benefits see signs that Italy has realised that it needs to change.

Italy was hit hard by the economic downturn in 2008 and 2009. Its economy contracted by about 5% in 2009, and unemployment has increased by about 35%. The ousting of Berlusconi and appointment of the technocratic government of Mario Monti was a signal to the world that a serious effort would be made to sort things out.

New agenda

Francesco Perrini, professor of management and corporate responsibility at Bocconi University, Italy’s leading business school, says Monti has a three-part plan: deal with the debt, restart growth, and then focus on sustainability. This could be the impetus many Italian companies need to start work on their responsibility agendas. “The crisis has forced companies to develop new thinking. There is a trend devoted to new opportunities related to sustainability,” Perrini says.

Mariarosa Cutillo of Valore Sociale, a non-profit organisation promoting responsible business, also believes that change is possible. At present, companies are “dealing with their day by day survival,” she says. However, “there is a new generation of managers who have a vision. They understand you can be profitable if you are more sustainable. It is something strategic.”

The window of opportunity might not be open for long, however. Italy faces elections in April 2013, and Monti has not said that he plans to bid for the continuation of his prime ministerial role. The risk is that Italy returns to its low-growth, low-innovation, weak-governance rut, and companies’ new thinking on sustainability and corporate responsibility starts to fade away.

References:

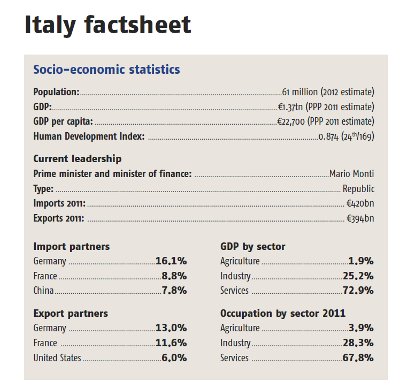

Socio-economic statistics obtained from recent publications from the CIA Factbook and the Human Development Index.

Guideline and standards statistics obtained during April 2012 from official website of each initiative.