Mark Hillsdon reports on how the U.S. president's proposed Growing Climate Solutions Act seeks to turn the industrialised agriculture of the country’s breadbasket from a biodiversity hazard into a CO2 sink through regenerative agriculture

“When the president of the United Sates starts talking about cover cropping, you know things are starting to change,” says Dr Rattan Lal, one of the world’s pre-eminent soil scientists, after Joe Biden name-checked the regenerative farming technique in a recent speech.

The administration has put a clear focus on agriculture as a way of combating climate change, describing it as a linchpin of the Growing Climate Solutions Act, a bill that environmental groups say has bipartisan support in both houses, and a real chance of becoming law this year. And that brings a smile to Dr Lal’s face, as he talks on Zoom from his office at the State University of Ohio.

Lal recently won the prestigious World Food Prize and has long been an advocate of climate-friendly farming, which enriches the soil so it can support healthy crops and perform its vital role as a carbon sink. Food security, nutrition, clean water, biodiversity, ending poverty – “all these things depend on healthy soil,” Lal says.

Although agriculture accounts for 30% of global greenhouse emissions, it’s also estimated that soil, and the plants that grow in it, can absorb around 30% of the carbon emissions swirling around in our atmosphere. Lal believes that as the largest stakeholders in environmental and climate and issues, farmers, ranchers and foresters must be part of the solution.

Incentivising all farmers is very important, whether it’s in the U.S. mid-west or an emerging farm in the Cerrado

One way of bringing them on board is to reward them for introducing sustainable practices, he says. The Biden administration, for instance, is considering a policy that would pay farmers $20 for every ton of carbon they left in the soil, whether through adopting regenerative farming techniques or simply not farming a certain area.

“Incentivising all farmers is very important, whether it’s a large farm in the mid-west United States or an emerging farm in the Cerrado [in Brazil],” says Lal. “We need to be pro-nature, pro-agriculture, and we need to be pro-farmer. We must give more respect and dignity to the farming profession, and compensation is essential.”

According to a recent report on climate-smart agriculture from the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), widespread adoption of climate-smart agriculture in the U.S. could cut farming’s contribution to the country’s GHG emissions from 9.9% to 3.8% by 2025.

Climate-smart agriculture is not new; no-till farming was introduced to the U.S. in the 1930s in response to the droughts and soil erosion that was turning parts of the country into a dust bowl. But such techniques were lost as U.S. agriculture became increasingly industrialised.

In the U.S. mid-west, the country’s breadbasket, industrial-scale corn and soybean production cover three-quarters of the area’s agricultural land, which has resulted in deteriorating soil health, groundwater contamination and depletion, and loss of biodiversity.

The environmental impacts extend well beyond the region, threatening the health and vitality of communities dependent on the waters of the Ogallala Aquifer and the Mississippi River, and contributing to the growing dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, where in 2018 algae blooms choked off oxygen in water and threatened marine life in an area the size of Delaware, and which causes $82m a year in damage to the U.S. seafood and tourism industries.

Biden’s focus on climate-smart agriculture supports the work of a growing number of organisations in the U.S. that believe if society expects farmers to use regenerative agriculture methods such as cover-cropping, crop rotation and managed grazing, they need to give them the tools and financial incentives to do so.

Cover crops increase soil organic matter, retain nutrients and alleviate soil compaction

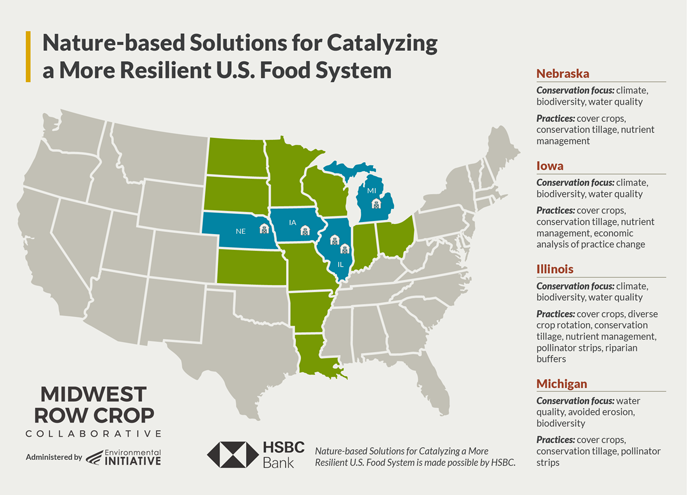

One of these is the Midwest Row Crop Collaborative, a partnership between NGOs WWF, Environmental Defense Fund, and The Nature Conservancy and corporate members Bayer, Cargill, Kellogg’s, PepsiCo, Unilever and Walmart.

In operation since 2016, the collaborative supports initiatives such as Saving Tomorrow’s Agriculture Resources (STAR), a free nationwide tool to assist farm operators and land owners in evaluating their nutrient and soil loss management practices on individual fields. In May, the collaborative received an infusion of $1.6m from HSBC’s new Climate Solutions Partnership Fund.

Unilever, one of the partners in the collaborative, in April launched its new Regenerative Agriculture Principles, based around regenerating soils, protecting water, increasing biodiversity, developing climate solutions and improving farmer livelihoods.

In Iowa, where healthy topsoil is eroding 10 times faster than it can be regenerated, it is working with soy farmers and soy oil suppliers on a cover crop programme, in which the cost of planting the crops is shared between Unilever and the farmer.

“The plants capture carbon in the air and feed it into the soil, where microbes use carbon for energy and keep it underground instead of releasing it back into the atmosphere,” explains Giulia Stellari, Unilever’s sustainable sourcing director. “Cover crops also increase soil organic matter, retain nutrients and alleviate soil compaction.”

But she said the greenhouse gas impacts of such interventions need to be validated and scaled. “It’s a big question that will need many stakeholders to come together to answer.”

If passed, the Growing Climate Solutions Act will help more farmers to participate in carbon markets

Other ways of supporting farmers are based on earning carbon credits for their labours. The recent slew of corporate carbon pledges has created a surge in demand for these credits, although historically there have been concerns around the accuracy of measurement and verification procedures, while the cost of setting up a scheme has put off many smallholders.

If passed, the Growing Climate Solutions Act will help pave the way for more farmers to participate in carbon markets by directing the U.S. Department of Agriculture to highlight practices that sequester carbon and reduce emissions, and create a certification process to help farmers verify the credits they generate. It would also create a farmer advisory board to work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to help ensure that carbon markets deliver financial value to farmers — not just buyers and intermediaries.

This is in line with one of eight key recommendations from the WBCSD report, which highlights the need to support emerging “revenue enhancement mechanisms” for farmers and ranchers, but at the same time bring a new transparency to the carbon market, and greater confidence to those companies investing in credits.

The Ecosystems Services Market Consortium (ESMC) is a collaboration from across the entire agricultural value chain, which has set out to create a national marketplace for carbon and water credits in the agriculture sector, while also making things fairer for the farmer, explains executive director Debbie Reed.

At the moment, she says, practices for sequestering carbon are complicated and expensive, while the costs of quantification, verification and protocol development mean that a farmer will often only receive between 5-10% of the full value of a credit.

ESMC is tackling this by building a much tighter infrastructure, with protocols developed on science- based targets, robust quantification tools and a verification process that relies on satellite technology rather than inefficient, time-consuming farms visits.

Directly providing the tools needed to verify outcomes, rather than relying on private companies “reduces the costs of generating the credits, so that more money can go to farmers,” Reed says.

We’ve got to address the benefits of land-based sequestration and flow money into that faster

“The mechanism will bring payment for things that we are demanding from them (farmers),” she says, whether it’s a buyer wanting a farm to reduce its carbon footprint, in order to align with their own sustainable goals, or pressure from consumers about the impact of the food they’re eating.

As more and more companies look for rigorous, science-based strategies for addressing the environmental impact of their operations, verified offsets such as those offered by Indigo Carbon, have emerged as another key tool for cost-effective carbon removal.

Representing a new income stream for farmers, Indigo Carbon allows companies to directly finance growers as they switch to farming practices that improve soil health and their profitability, while reducing farm emissions and removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

Companies including Barclays, IBM and JPMorgan Chase have already signed up to what Indigo calls “the global effort to leverage agriculture as a meaningful climate solution”.

Elsewhere, the WBCSD report highlights how the Regen Network is building a platform for farmers to monetise their ecosystem services, with blockchain technology helping to assure greater accountability. The California Healthy Soils Program is among several of the state’s land-based projects that is providing financial support for conservation projects that improve soil health.

Diane Holdorf, who heads up the WBCSD’s food and nature programme, says there is a growing awareness of climate risk among farmers. This is being backed up by a generational shift, with younger farmers coming in who are open to new ideas and technology, while there has also been an increase in interest, beyond the agricultural community, in understanding how it can be a force for good.

“We’ve got to address the benefits of land-based sequestration and flow money into that faster than we have been able to do,” Holdorf adds.

“The financial innovation space is really taking off... this is where we see the opportunity for healthy soils being viewed more as a carbon asset than simply as a place where food is grown.”

Helping America’s small landowners reap rewards for protecting forests

Forestry offsets company NCX is trying to bring America’s small landholders into the carbon credits market by reducing the upfront costs involved in creating a carbon inventory and a management plan, explains co-founder Zack Parisa.

Small landholders together own 36% of U.S. forests, more than any other group, yet have until now “been systematically excluded from these markets” because it can take two years and $100,000 to create just one of these carbon-monitoring projects.

Through its Natural Capital Exchange, NCX (formerly SilviaTerra) is “connecting landowners with companies looking to achieve net zero, using a data-driven approach,” says Parisa.

In partnership with Microsoft, the company has created a high-resolution satellite map of the U.S., measuring every acre of forest every year. The system is freely available and allows landowners to assess their land and its carbon sequestration potential, without any upfront costs.

At the moment, only one-year commitments, dubbed “harvest deferrals”, are on offer, in which small landowners are paid to reduce the number of trees they cut, leaving them standing so they continue to soak up carbon. The credits are bought by companies as offsets, with the money going directly to the landowners. The short-term nature of the contract has proved popular too, with payments made after 12 months rather than having to wait decades before a credit is verified.

Being able to match different solutions to different settings is something the system will be able to pick up on, too. So, while some forests are best suited for thick cover that simply soaks up carbon, for others thinning trees may be a better option, improving habitats and making the landscape more resistant to wildfires.

Parisa, speaking on a panel at May’s Transform USA virtual event, said it was important to ensure that “landowners and forest-based communities are rewarded for creating these important outcomes beyond just what gets removed from these sites, but what gets added to them as we build regenerative cycles into the decisions we make.”

Another programme aimed at smaller landowners is the Family Forest Carbon Program, which was kicked off with a $7.3m investment from Amazon. By making payments for thinning and removing invasive species, the FFCP hopes to release the true potential of these small, wooded parcels of land to sequester carbon.

How Stony Creek Colors is turning tobacco farmers into sustainable indigo suppliers in Tennessee

Tennessee enterprise Stony Creek Colors is a female-led startup that produces a naturally grown replacement for chemical-laden synthetic indigo, which is used in more than 99% of blue jeans. Founded in 2021 by Sarah Bellos, Stony Creek has received support from The Nature Conservancy, in a partnership with venture fund managers iSelect to identify emerging agri-tech solutions.

Stony Creek works directly with growers, many of them former tobacco farmers, to improve soil health on their farms, with alternative nitrogen-fixing legume row crops such as Indigofera tinctoria and Indigofera suffruticosa. Both have low fertiliser requirements, too, and don’t require insecticides due to naturally occurring pest resistance.

After extracting the dye, the used plants are dug back into the soil, and preliminary carbon modelling shows that through this composting the crop captures and returns nearly 4,000 kilograms of CO2 per hectare to the soil.

Stony Creek has focused on lowering the barriers that are preventing tobacco farmers from moving into the alternative crops by developing a system that fits with their existing resources and equipment. This involves providing high-yielding indigo seed, harvesting the crop to ensure farmers don’t need to buy new equipment and employ more labour, before processing it and selling the high-purity blue dye to denim mills, which produce for customers including Levi Strauss and Cone Denim.

“The plant-based indigo is a climate-positive chemical replacing the petroleum-derived indigo used today in dyeing all denims,” explains Bellos. It’s also free from aniline, cyanide and five other toxic chemicals used to make synthetic indigo for the fashion industry. “Stony Creek’s product uses sunlight, seeds and water,” she adds. The company is also looking at ways to reduce wastewater in the dyeing process.

At the moment, she says, the use of the plant-based dye adds about $1.50 to the cost of a pair of jeans, although “advancements in yield, bringing the plant to scale – through TNC funding and other partners – and other technology innovations will help decrease this further over time.”

In March, the company raised more than $9m in a new round of financing to scale its operations and expand its natural indigo dye to more mills.

Mark Hillsdon is a Manchester-based freelance writer who writes on business and sustainability for The Ethical Corporation, The Guardian, and a range of nature-based titles including CountryFile and BBC Wildlife.

Main picture credit: The Nature Conservancy

This article is part of The Ethical Corporation summer 2021 in-depth briefing on natural capital. Click on the cover to download your digital copy for free.