While German companies embrace corporate sustainability, they are less sure about their social responsibilities

There is a sharp division in Germany between the notions of corporate responsibility and sustainable business.

In many of the more traditional boardrooms in Germany there is still a perception of corporate responsibility – particularly the social aspects – as something for the Gutmenschen, or do-gooders.

The backbone of the German economy is family-owned exporting firms that often work in business-to-business sectors. They are not visible to consumers and so corporate responsibility “is not something they’re looking to gain a competitive advantage with”, says responsibility blogger Fabian Pattberg. “They say ‘don’t give me this Gutmensch argument’.”

There is a black and white view in some boardrooms that there are Gutmenschen and there are people who make money. Several factors contribute to this climate. Most German companies are not listed and so not publicly scrutinised. They work within a strict legislative framework compared with those of other countries, and must obey multiple environmental and social regulations. It’s very bureaucratic, which means companies resist additional obligations.

There is some truth in the argument that German companies do not need to have separate social programmes, because the government, through the obligations it places on business, is doing it for them. Germany scores very well compared with other nations on issues such as recycling and renewable energy – which now makes up about a fifth of the country’s electricity supply, compared with about 7% in the UK. The German decision to phase out nuclear energy by 2022 will boost the country’s green credentials.

Employee involvement

Germany also has a system of works councils, through which employees even in very small companies have a right to participate in staffing decisions. Germany ranks as one of the world’s most expensive countries in which to employ staff, and German companies, which often work in high-tech sectors, need highly qualified people. The result is that companies work hard to retain their human capital, and emphasise good relations with the communities in which they are based. Large private employers are noted for their extensive philanthropy.

But when it comes to other issues that fall into the corporate responsibility bracket, German companies do less well. “Reporting is not really a priority,” says Pattberg. Non-listed German companies, some of which are extremely large, have a reputation for lack of openness.

Germany also lags other countries in terms of boardroom diversity. Although one third of the government’s ministers are female, Germany’s top 30 companies can count their women management board members in single figures. Deutsche Bank chief executive Josef Ackermann angered the government in early 2011 by saying more women would make boards “more colourful and prettier”. Deutsche Bank has no female top managers.

Commitment to sustainability

German bosses excel at taking hard-headed business decisions, however. Elsewhere, companies have to be reminded regularly about the virtues of thinking longterm and looking after customers and employees. In Germany, no reminders are needed, and this translates into increasing buy-in to the concept of sustainability.

German companies look to the future and “see the demand or business opportunities” arising from sustainability, says Hannes Partl, a sustainability consultant with PE International. The largest companies are moving to “sustainability 2.0, really integrating it into their business strategies”, he says.

In other countries, companies talk sustainability long before they really start to walk it, but in Germany the situation is reversed: companies put in place sustainability strategies, and only then think about marketing them. “They are not waiting for the market to push them,” Partl says.

The emphasis on sustainability is a response to factors such as rising commodity prices, and a recognition that cheap energy cannot last for ever.

Multinational giants such as BASF, Henkel and Siemens score well in international sustainability indices. Partl says that “smaller companies are generally slower because they don’t have the capacity”, but nevertheless sustainability is “cascading down”.

One of the most interesting sustainability initiatives is Puma’s completion in 2011 of an environmental profit and loss (EP&L) accounting exercise, which assessed in monetary terms the sporting brand’s environmental footprint. Puma’s chairman Jochen Zeitz says the assessment was about the bottom line. The benefits, he says, will include savings on raw materials, greater manufacturing efficiencies, reduced waste and “real impactful, tangible reductions” of environmental costs.

In the long run, savings “will 100% outweigh the cost of putting this in place”, Zeitz says. Others are keen to benefit from the German expertise. “Various companies who are interested in incorporating an EP&L into their business model are already engaged with us.”

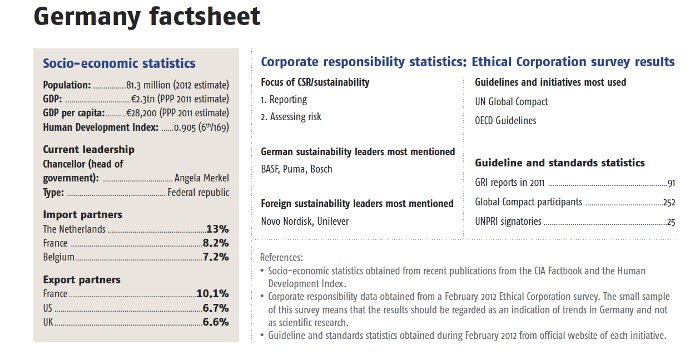

Germany corporate responsibility factsheet

References:

Socio-economic statistics obtained from recent publications from the CIA Factbook and the Human Development Index.

Corporate responsibility data obtained from a February 2012 Ethical Corporation survey. The small sample of this survey means that the results should be regarded as an indication of trends in Germany and not as scientific research.

Guideline and standards statistics obtained during February 2012 from official website of each initiative.