In a new series of in-depth profiles of the people transforming business for good, Oliver Balch talks to Google's head of sustainability about the challenges of ensuring the giant tech company is doing no evil to the planet

Few environmental managers are granted honours by the military. But then not many environment managers get tasked with cutting the carbon footprint of a fleet of 430 or so war frigates, aircraft carriers, submarines and other naval craft.

Kate Brandt, Google’s lead for sustainability since 2015, is certainly not shy of a challenge. After her stint at the US Navy, she switched her carbon-cutting attentions to the US Federal government’s portfolio of physical assets – a small matter of some 360,000 buildings and 650,000 vehicles, plus an annual procurement budget of around $445bn.

It’s tempting to think that her new life at Mountain View, Google’s California headquarters, must be a breeze by comparison. It’s not. Admittedly, Brandt’s brief doesn’t cover the full gamut of Google’s external responsibilities. Tricky ethical issues like freedom of speech in China or dodgy election advertising or corporate taxes in Europe fall elsewhere.

But Brandt is clear: anything to do with environmental performance happens on her watch. And this is Google we’re talking about, one of the largest internet companies in the world. It operates 14 vast data centres in four different continents, and is adding new facilities all the time. It is also responsible – albeit indirectly - for the energy consumed by the billions of people who use search, Gmail, YouTube and Google’s many other products.

Fortunately for Brandt, her new employer isn’t starting from scratch. Environmental efficiency has been a “core value” of the company since its inception 19 years ago, she says. By way of proof, she notes that the company’s data centres run on 50% less energy than the industry average and that six have achieved 100% landfill diversion. |

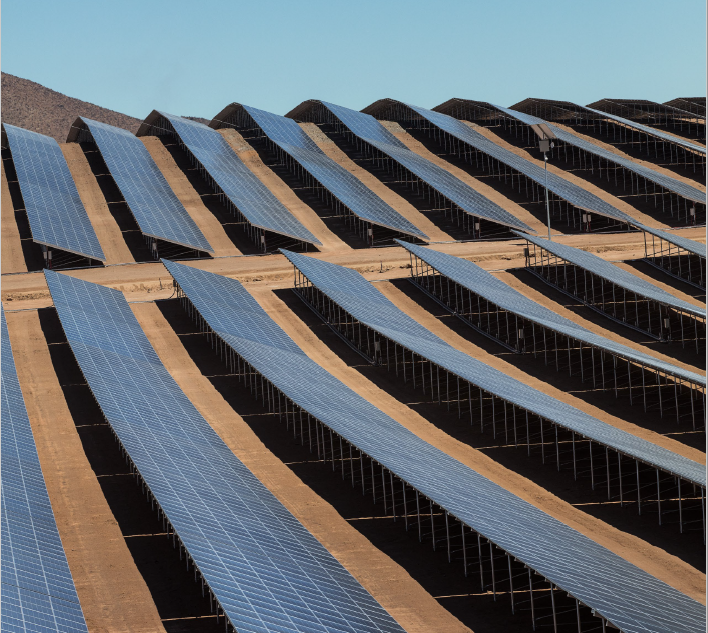

Environmental efficiency aside, where Google can claim to be really breaking the mould is in its championship of renewable energy. The internet giant has so far committed $2.5bn to renewable projects. That’s a big chunk of change, most of which is being ploughed into supporting new solar and wind power facilities.

Substantial as Google’s renewable purchasing now is, however, Brandt admits that it is “by no means the end of the work that we want to do in this space”. The company still produces 2.9 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent every year. So while Google is technically 100% carbon-neutral, it gets there by offsetting the dirty stuff.

One of the challenges that Brandt faces in delivering on the company’s end goal of “a zero-carbon world” is how to help build out the so-called “green grid”. Google’s strategy for now is to correct shortages in power-generation capacity in the regions where it operates, such as Taiwan and Singapore.

For all Google’s financial might, it won’t bring about a renewable revolution by its own efforts alone. No, the potential of this bona fide Silicon Valley giant to make the planet greener lies elsewhere: in technology.

As Brandt clarifies: “It’s not only our impacts that we’re thinking about, it’s the nexus between technology and sustainability, too.”

Just think about it a second: every Google search logged; every road and river mapped; every Gmail message registered. That’s not even taking into account the internet-beaming balloons, smart contact lens, autonomous cars and copious other wacky-sounding products that Google has become known for. What if all this data-collating, number-crunching, pattern-detecting computational power could be used for planetary purposes?

The cloud gives an inkling of what’s possible. Research from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests that if all office workers in the United States moved their email and documents to the cloud, it would reduce IT energy use by up to 87% – enough to power the city of Los Angeles for one year.

Or consider smarter, greener transportation. Google Maps offers transit information for more than 6,000 bus services and other public transport providers in 20,000 towns and cities worldwide. So for smartphone users jumping on a bus, tram or train has never been easier – persuading them out of their gas-guzzling cars and thus reducing their emissions.

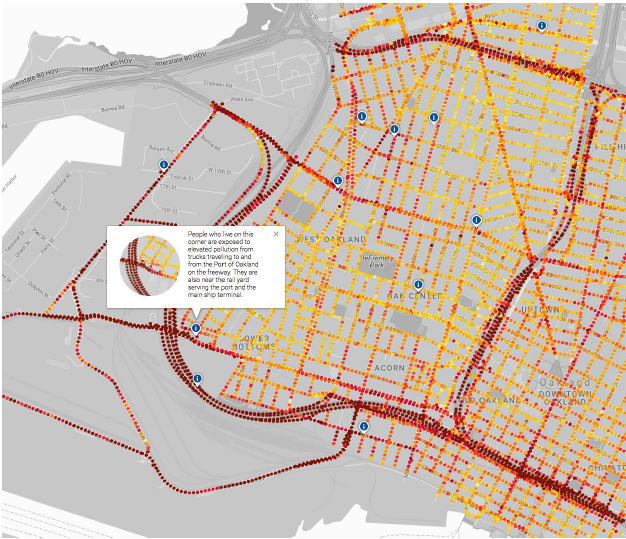

To date, it’s mapping solutions like this where many of Google’s early wins have occurred. Five years ago, for instance, the company embarked on a breakthrough initiative with the Environmental Defense Fund to prevent methane leaks. Methane, which has 84 times the short-term warming effect of carbon dioxide, is constantly escaping from the 1.3 million miles of natural gas pipelines in the US.

Previously, the ability of utilities to identify these leaks has been limited, leaving some pipes seeping the potent greenhouse gas unchecked for months or even years. Google’s solution, together with scientists from Colorado State University, was to attach a methane analyser to the cars that were already collecting data for its Street View service.

The initiative has so far led to the discovery of more than 5,500 leaks and the development of methane maps for 11 US cities. Last year, Google extended the initiative to include other air pollutants, such as NO2 and CO2 black carbon. The scheme has initially been trialed in Denver and various regions of California.

Other neat eco-services that are emerging off the back of Google’s mix of mapping capabilities, computer power and secure data storage include tools to track forests disappearing, lakes drying and glaciers receding in real time.

What is intriguing about such examples is the organic nature of their creation. Brandt doesn’t have teams of R&D experts at her beck and call. Nor does she sit in her Mountain View office firing off orders to adapt this Google service or that for environmental ends.

Eco-innovation doesn’t adhere to corporate hierarchy, she says. Indeed, many of the best applications of Google’s technology and services originate outside the organisation altogether. Much of the creative input for Global Fishing Watch, a mapping service that tracks the world’s commercial fishing fleet, for instance, came from charities SkyTruth and Oceana. Likewise, the World Resources Institute was instrumental in leading the development of the Global Forest Watch app.

“We have found that through partnerships is how we are able to really do this work in a deep way and to ensure that it’s as useful as possible,” she says.

That’s not to say that “Googlers” (as Google’s staff call themselves) are all sitting back twiddling their thumbs. Far from it. Under the company’s much cited “20% time” policy, full-time employees are encouraged to spend up to a fifth of their working week pursuing private projects. To Brandt’s evident delight, many turn their creative juices towards helping the environment.

She reels off a few of the resulting innovations. Like machine-learning in the company’s data centres, which has led to a 15% decrease in energy use in the facilities where it has been piloted. The original prototype was the brainchild of an individual efficiency engineer who spent “six error-prone, head-banging months” developing a proof-of-concept model.

Or Project Sunroof. US householders just need to tap their postcode into the online tool and, hey presto, up comes an immediate analysis of the best solar panels for their property, the best way of financing them, and the best local firm to fit them.

Today the initiative, which uses Google Earth rooftop satellite imagery, has a whole team supporting it. But it started life as a 20% time project of an engineer in Massachusetts, who was bent on finding a way to simplify the shift to domestic solar after struggling to install solar panels on his own home.

This bottom-up approach to innovation is in keeping with Google’s decentralised approach to environmental management. Brandt may have overall responsibility for the company’s performance, but the day-to-day work is done by separate sustainability teams across Google’s many different business units.

“In my role, I work across all these teams on the overarching strategy, ensuring that we’re coordinated, that we’re remaining ambitious, and that we’re reporting on our goals and that we’re reaching them,” says Brandt.

So, after more than two years in the job, what’s the verdict? Brandt is too modest, or too astute, to answer that question directly. Instead, she points to Google’s environmental progress report (only its second ever), which was published earlier this month.

The 55-page report makes for impressive reading, full of bold targets (notable, 100% carbon neutrality later this year) and granular data (“carbon intensity per full-time equivalent employee” and so forth). But impressive reading is partly what such reports exist for.

Brandt knows this only too well; she oversaw the writing of it. Yet for that same reason, she’ll be aware of the future challenges it includes as well. Not least, the US internet provider? publicly states its wish to “lead the way in improving people’s lives while reducing or even eliminating our dependence on virgin materials and fossil fuels”.

Progress here will require this experienced sustainability leader to maximise every ounce of ingenuity from Google’s army of engineers and tech wizards. It will also involve engaging more and more academic research centres and not-for-profit partners. Last but not least, it means tapping the creative genius of the internet-using public at large – something Google has yet to do in a meaningful way.

Pulling all this off will not be easy. Indeed, the very act of trying probably deserves a medal in itself.

Kate Brandt will be speaking at Responsible Business Summit West in San Francisco on 14-15 November.

google street view Environment renewables silicon valley Global Forest Watch Project Sunroof Google Earth