Mike Scott assesses whether the technology will live up to its much-vaunted potential to be the Holy Grail of climate action, transforming supply chains and removing barriers to a clean energy future

Blockchain is one of the world’s most overhyped technologies, but there are hopes that it may help to tackle one of our most intractable problems – climate change.

Blockchain, also known as distributed ledger technology (DLT), is the enabling force behind cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. One of the main things people know about cryptocurrencies is that it takes huge amounts of energy to “mine” the coins.

Generating bitcoin uses 2.55 gigawatts of energy a year, almost as much as the Republic of Ireland

PwC economist Alex de Vries estimates that generating bitcoin uses 2.55 gigawatts (GWs) of energy a year, almost as much as the Republic of Ireland. Miners use this energy by running computers to solve complex codes, known as a proof of work, to earn the currency. To limit the amount of currency in circulation, these proofs of work are becoming more complicated over time, requiring ever more computing and electrical power. In addition, many miners are in China, and use electricity produced by coal-fired power stations, the most polluting form of energy.

However, blockchains in general do not have to use a lot of power, says the Climate Ledger Initiative, which explores how distributed ledger technology can help to tackle climate change: it is simply a feature of how cryptocurrencies are generated.

PwC believes blockchain could potentially transform many existing processes in business, governance and society, without breaking the energy bank.

In a report for the World Economic Forum, it says that “as blockchain matures, its energy intensity will reduce and the opportunities for blockchain to help the planet may well far outweigh its energy-use limitations”.

PwC describes blockchain as “a foundational emerging technology of the fourth industrial revolution, much like the internet was for the previous [or third] industrial revolution”. Its defining features, it adds, are “its distributed and immutable [or unalterable] ledger and advanced cryptography, which enable the transfer of a range of assets among parties securely and inexpensively without third-party intermediaries”.

There is nothing inherently “clean” about blockchain – the energy majors have embraced the technology across their operations, seeing it as a multi-billion-dollar opportunity to improve performance in every part of the industry as it digitises all of its processes and operations. The applications range from energy trading to grid management to optimising supply chains.

Blockchain is the Holy Grail for implementation of various climate change policies and enforcement of climate regulations

But it can help reduce the impacts of climate change, according to Alastair Marke, director general of the Blockchain Climate Institute. “It’s the Holy Grail for implementation of various climate change policies, including renewable energy deployment, carbon markets, international financial transfers and enforcement of climate regulations.”

But, Marke clarifies, “blockchain itself is not a solution to all these policy, regulatory or implementation issues. It is an enabler of many other innovative solutions that were not possible in the past.”

The Climate Ledger Initiative says there are three main benefits of blockchain technology:

-

Data records on a blockchain are immutable through a permanent ledger, increasing transparency

-

Blockchain technology brings trust to peer-to-peer transactions, which is particularly important where regulation is weak or governance is decentralised

-

Smart contracts – applications that can automatically execute the terms specified in a contract on a blockchain – increase efficiency and reduce transaction costs.

Owen Hewlett, chief technical officer at The Gold Standard voluntary carbon offsets scheme, says the potential of blockchain as a climate tool started to emerge at the Paris climate conference in 2015.

The decentralised nature of the Paris Agreement and its governance structure, whereby countries are responsible for setting and monitoring their own climate solutions, requires new approaches to registries and tracking systems to handle a wide range of rulesets for accounting and reporting and to allow for trusted, networked carbon markets.

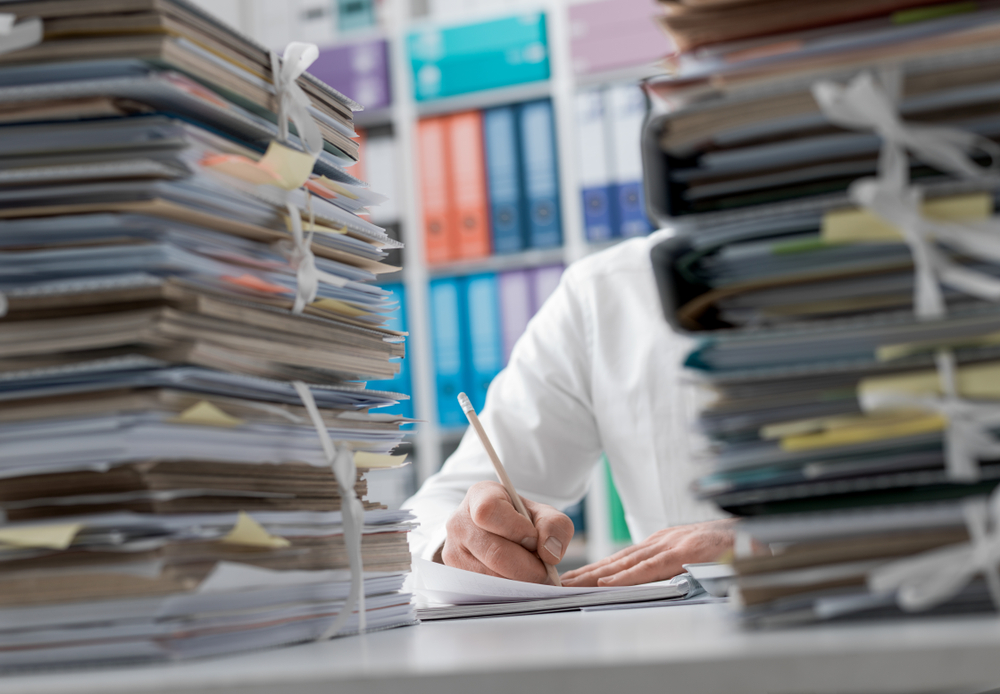

Distributed ledger technologies can also help in measuring, reporting and verification (MRV) processes, unlocking new ways to ensure that emissions-reducing projects are having the impact they claim, in ways that are more accurate, transparent and cost-effective.

Using blockchain 'can take all the pain out of collecting data and automate parts of the verification process'

“Because a blockchain is decentralised and immutable, we can use it to gather data at a project level and have it time-stamped,” Hewlett says. “That’s a big improvement on what happens now, which is that a lot of data is collected by hand, by survey or through meter reading.”

He cites the example of cookstoves, which reduce greenhouse gas emissions and premature deaths from local air pollution. To earn carbon credits, cookstove projects need to show how much the stove has been used so its impact on emissions can be measured. Using a blockchain-based stove use monitoring system “can take all of the pain out of collecting the data, automate parts of the verification process and makes the whole process much more credible because it is tamper-proof,” Hewlett says. The system also allows credits to be issued almost in real time, rather than at the end of the three-year compliance period, which is what happens now.

However, there is still a significant cost issue: cookstoves cost up to $35, while a monitor currently costs between $75 and $300, although some of this cost is recouped in reduced labour costs, and the cost of monitors is likely to fall as usage increases.

Supply chain transparency is one area where companies see great potential for blockchain. Unilever has a pilot project investigating blockchain’s potential in its supply chain, according to the Climate Ledger Initiative. Working with a retail firm, a packaging firm and several banks, the consumer goods company is developing a system to track and reward tea suppliers for sustainable farming practices. Information about their produce, including quality, sustainability metrics and price, is stored on the blockchain, enabling them to be rewarded by banks with preferential terms.

And blockchain developer ConsenSys is working with WWF and Fiji tuna processor Sea Quest to test a traceability tool to help stamp out illegal fishing and human rights abuses in the Pacific Islands’ tuna industry.

Blockchain shines a light on energy demand and supply and enables peer-to-peer trading

Blockchain also facilitates distributed energy generation by allowing consumers to buy and sell their own energy. Historically, national energy systems relied on large, centralised power plants to produce electricity and send it over transmission networks to households or industrial and commercial customers. But new clean-energy technologies such as wind and solar, energy storage and smart grids, along with digital tools such as the internet of things, artificial intelligence and machine learning, are allowing a greater number of smaller producers to generate and transmit electricity.

The growing complexity of power management requires new solutions, of which blockchain is one. One way it does this is through “smart contracts”, which allow real-time pricing and make the grid more flexible. They automatically execute the terms specified in a contract on a blockchain as long as certain conditions have been met, increasing efficiency and reducing transaction costs.

Blockchain also enables consumers to sell excess power to the grid at wholesale rather than retail prices, and to sell to buyers in their local communities.

“Blockchain shines a light on energy demand and supply, and helps to match it up better,” says Mark van Rijmenam, a blockchain strategist. “It enables peer-to-peer trading by taking away the need for intermediaries and cutting costs.” This same characteristic also means that it could be used to link carbon-trading schemes from different countries.

Increased digitalisation and interconnection have led to greater concerns over security risks such as hacking and cybercrime.

Blockchain, due to its distributed nature, can make networks much more secure, if implemented correctly. In co-ordination with burgeoning technologies such as AI, blockchain can help secure networks and grids, the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) points out, because it is managed by a distributed group of peers, rather than by a central server or authority.

Between the start of 2017 and September 2018, more than 50 start-ups were launched working on blockchain applications in energy

“This technology is enabling a new world of decentralised communication and co-ordination, by building the infrastructure to allow peers to safely and quickly connect with each other without a centralised intermediary,” Irena says in a report on blockchain and renewable energy. Cryptography ensures security and data integrity, while privacy remains intact, it adds.

The potential of the technology has led to a surge in the number of companies looking to become involved in the sector, with Irena reporting that between the start of 2017 and September 2018, more than 50 start-ups were launched that are working specifically on blockchain applications in energy, raising more than $320 million.

“Today, there are more than 70 demonstration projects deployed or planned around the world, such as LO3’s Brooklyn Microgrid project, where customers can choose to power their homes from a range of renewable energy sources, and people with their own solar panels can sell surplus electricity to their neighbours,” the agency says.

“The Energy Web Foundation (EWF) is building an open-source, blockchain-based digital infrastructure for the energy sector with a growing portfolio of cutting-edge pilots. Innogy, a subsidiary of German power giant RWE, is using EWF’s Energy Web Blockchain to authenticate users and manage billing at electric car-charging stations.”

However, the technology remains in its very early stages and there is a long way to go before we will know whether its potential will be realised. “If harnessed in the right way, blockchain has significant potential to enable a move to cleaner and more resource-preserving decentralised solutions, unlock natural capital and empower communities,” PwC says.

“However, if history has taught us anything, it is that such transformative changes will not happen automatically. They will require deliberate collaboration between diverse stakeholders ranging from technology industries through to environmental policymakers, underpinned by new platforms.”

There are many ways to operate blockchain networks, and the mining process is not always necessary for private key networks

Barriers that still need to be overcome include a lack of user trust and adoption, security risks, legal and regulatory challenges, challenges in scaling up the technology in a way that makes it able to operate on multiple systems, and blockchain energy consumption.

There is already a lot of progress being made in this area, with blockchains such as Ethereum using a “proof of stake” protocol that uses about 12-14 times less energy than bitcoin transactions.

Others are developing “proof of importance” protocols, which are simpler and more accessible, while next-generation computers will help by offering higher computing power for less energy usage. “There are many ways to construct and operate blockchain networks, and the mining process is not always necessary for private key networks,” PwC says. “Consensus can be achieved in a much more energy-lean way. ‘Proof of authority’ networks, for example, only allow authorised authorities to validate networks. When authorities don’t have to compete for access, as in crypto-mining, there is less energy consumption throughout the network as a whole.”

Even so, established stakeholders will be slow to accept what is a revolutionary technology, says Marke. “Bureaucracies around the world have been working with centralised systems for the past century. It will take some time for them to change to a decentralised model.

“Another issue is that blockchain is an invisible infrastructure, so psychologically the value is not very tangible to the general public until there are some promising use cases out there that demonstrate the potential.”

Nonetheless, in a world where the energy system will be subject to the triple forces of decarbonisation, decentralisation and digitalisation, blockchain is a technology that is likely to come into its own before too long.

Mike Scott is a former Financial Times journalist who is now a freelance writer specializing in business and sustainability. He has written for The Guardian, the Daily Telegraph, The Times, Forbes, Fortune and Bloomberg.

This article is part of the in-depth briefing Stepping up to 1.5C. See also:

Why even Republicans are backing a Green New Deal for America

Can UK Acorn carbon capture project grow into solution to industry emissions?

Drax targets negative emissions with world’s first biomass CCS project

From cookstoves to carbon markets: how blockchain is supercharging sustainability

‘We’re rethinking our entire business, from supplier agreements to future technologies’

‘Divestment isn’t a badge of honour; it’s a failure of engagement’

‘If companies want to meet climate targets, they have to take employees on the journey’

‘We can only achieve a 1.5C world if science and business work together’

Blockchain Bitcoin Climate Ledger Initiative smart contracts The Gold Standard carbon credits Paris Agreement