Companies have to listen to the roar of the left behind and tackle issues ordinary people care about, leading thinkers say

“The Labour Party is more at home talking about the issues that swirl about the Islington dinner party, [like] fair trade and climate change, [than those] which concern real working people in working class communities, like immigration and social mobility.”

With that scathing remark, the new populism blew a big fat raspberry in the face of the liberal sustainability consensus, so lovingly assembled over the past 25 years. The speaker was Paul Nuttall, the new leader of the UK Independence Party (Ukip), gunning for Labour voters in the party’s traditional heartlands. But it could easily have been any one of 2016’s other defiant insurgents – from Trump to Le Pen – riding a wave of popular anger, and channelling it at an array of progressive causes dear to the hearts of sustainability advocates, now derided as part of the liberal establishment.

For anyone in the sustainable and ethical business world, this was the equivalent of a slap in the face with a cold fish. Society was broken, said the insurgents, and sustainability wasn’t going to fix it. Indeed, in some eyes, it was even part of the wrecking ball.

The shock was palpable. After all, it had all been going so well. Sustainability had, over the last three decades, slid from fringe to centre. Every major corporation worth its salt had embraced it – at least in theory. Business had lobbied governments for tighter environmental regulations (something unthinkable even 20 years ago) and governments had responded – culminating in the triumph of the Paris climate accord. Of course, there were failures and setbacks, but overall the assumption was that sustainable business was on the side of the angels – and the people. It was, surely, part of the solution. Now, more or less out of nowhere, it was being savaged as part of the problem – just, ironically, at a time when the latest scary climate statistics suggest it’s needed more than ever.

Sustainability’s limits

So how can it best respond? Answers at the moment are thin on the ground, but among leading figures in the ethical business world, some harsh introspection is under way. And it starts by trying to understand the roots of the anger that fuelled Brexit, Trump and more besides – and the CSR world’s failure to anticipate it.

Veteran campaigner Jonathon Porritt identifies the failure of business to go beyond mainstream sustainability issues as part of the problem.

“There’s no doubting that corporate sustainability practitioners have achieved a great deal. But by and large they have stayed within ‘safe’ limits – not really challenging the prevailing political and economic status quo. Issues such as shareholder supremacy and fiduciary duties, taxation, outsourcing and levels of pay (at the top and bottom end of the scale) have stayed more or less untouched.”

This left them all too exposed when the tides of populist anger came surging, Porritt says. “By avoiding some of those central failings of present day capitalism, while at the same time pulling down astronomical salaries, they’ve become directly identified with a system that is not only unsustainable, but downright unfair.”

Ah yes, those salaries. As Bank of England Governor Mark Carney pointed out, this has been the first “lost decade” in terms of wage growth since the 1860s, “when Karl Marx was scribbling in the British Library”. Lost, except, to those at the top of the tree, who continue to receive pay packages out of all proportion to the vast majority of their employees – or, in the eyes of those struggling to get by – to the value of their work. Wanda Wyporska of the Equality Trust recalls former City Minister Lord Myners’ comment that he would love to ask the notoriously well-paid advertising executive Martin Sorrell, “What do you do for £77m a year that you wouldn’t do for £76m?”

Technology over expertise

Inequality is one thing; insecurity another. You might cope with working for a pittance compared to your bosses, but not if they’ve just relocated your job to China (and earned a bonus in the process). Their rising tide certainly hasn’t floated your boat. “There’s a significant portion of the population whose boats have actually sunk,” says Jim Woods of the sustainability forum The Crowd, which staged an event on the “broken society” theme late last year.

As inequality widens and globalisation bites, so old certainties dissolve. Keith Clarke, former CEO of engineering consultancy WS Atkins, has seen the changes over a generation in business. “Post-war, the expectation was that tomorrow would be better. This year will be better than last year. My children will be better off than me. Now that’s all gone.”

He sums up the shift that has swept through the traditional industrial heartlands of Britain and the US. “Once upon a time, if you wanted to make knives, you made them in Sheffield. Because that’s where the knowledge base was, and so you probably had a factory there. Now I can make knives – or gearboxes, or whatever – anywhere I like, because technology has replaced the need for skilled, knowledgeable labour. I can buy the machinery, set up a factory in Shenzhen, five years later move it to Malaysia. I can move technology, and I can move knowledge.” He concludes: “The mobility of capital changed things, the mobility of knowledge is changing things a lot faster.”

And it’s hitting the middle classes for the first time, too. “I used to need, say, 20 middle managers. Now I don’t actually need any. I can do a whole lot more with data, so I just need a few IT people, a few salespeople, and the rest of you are a commodity. We’ve seen the commoditisation of the labour force in virtually every sector – and that’s where the technology is taking us.”

Location, location, location

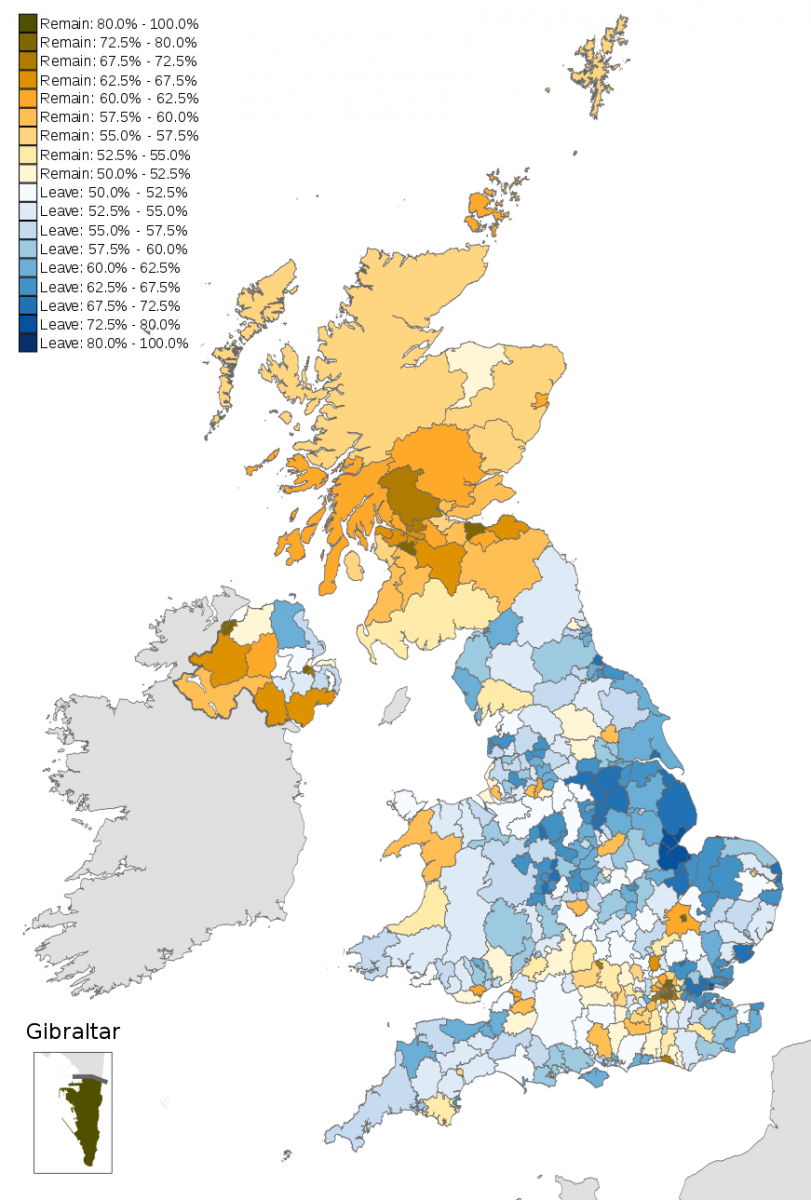

The result of all this upheaval, says Sally Uren, chief executive of Forum for the Future, is “an incredible divide between the haves and the have nots”. And it’s not just a divide of wealth, but of geography, too. “London has been powering ahead. It’s the home of a metropolitan elite, it’s well connected, it’s full of opportunities. The same is true for the east and west coasts of the US. These are the places that voted overwhelmingly Remain, and Democrat.”

These are also the heartlands of the sustainability and ethical business world. And it’s a world away from those old industrial and rural heartlands. Their vote for Brexit and for Trump, says Uren, was “a roar from a whole demographic that feels left behind, left out. They are suffering from an inequality which is directly linked to their geographic location.”

She talks of Long Eaton, a small town in Derbyshire where she grew up. “The opportunities are just so few. A job in Costa Coffee attracts hundreds of applicants, most of them graduates.” The area voted heavily for Brexit. In it and other provincial British towns, says Uren, “You can see the metaphorical tumbleweed coming down the high street, which is just full of charity shops”.

Woods points to Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, once one of the country’s most prosperous harbour towns – “now awash with bookies and pound shops” – and a population resenting immigrants working for rock-bottom wages. It too backed Brexit by a massive majority.

This deep-seated divide helps explain why appeals to safeguard the economy by voting Remain fell on deaf ears. Stephen Kinnock, a strongly pro-European Labour MP, sums up the reaction of many who voted Leave: “They said, ‘You’re trying to get me to vote for the status quo – but the status quo isn’t working for me, so why should I vote for it? Your economy isn’t my economy.’”

It’s an argument echoed by Helena Morrissey, until recently CEO of Newton Investment Management. She points to deep public cynicism over the fact that the architects of the 2008 financial crash appear to be still standing amidst the havoc they wreaked on ordinary people’s lives. Combined with rising inequality and rapid shifts in the skillsets required by employers, she says, this has helped create massive pressure points that neither government nor business is addressing. “Many people in leadership positions are either oblivious to this, or in complete denial.”

And, she could have added, so are many CSR professionals. Because, with a very few exceptions, they too failed to spot the rising pressure around inequality on their own doorstep, many agonising over the impact of globalisation in Ladakh or West Africa were blind to its impacts in Long Eaton or West Virginia. In that respect, Paul Nuttall is right. Sustainability wasn’t hitting home.

The business-society nexus

As Woods puts it: “The issues that are top of the agenda for CSR – like climate change, resource efficiency and so on – are nowhere near the top of the agenda for society, and we need to grasp that, and fast. The sustainability movement should be the guardians of the relationship between business and society. That’s a vital role. And that means we need to start looking at stuff like zero-hour contracts, the gig economy, automation – the really live issues. If [CSR professionals] fail to get their head around that, then they’re doing a disservice to their businesses and to society.”

Morrissey agrees: “It’s time for the CSR community to move centre stage. This should be their moment.” And it is in business’s self-interest more widely to do so. After all, as has often been said, you can’t have a successful business in a failing society.

Both Morrissey and Kinnock float the idea of more regulation: specifically, reforms to the Companies Act to compel business in general to play a more constructive role. Might that not be a touch heavy-handed? “I’m all for voluntary change,” says Morrissey, “but I’m a bit worn down by people saying one thing and doing another … I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told by directors that, yes we had to go with the short-term outcome, accept the bid or whatever, even though it destroyed jobs or destroyed the community or wasn’t really good for the company, because we took legal advice and were told we were in danger of being sued by the shareholders.”

Kinnock goes further: “I’d like to insert a ‘balanced purpose’ clause into the Act, so you can’t incorporate a company unless you have a clear statement covering people, planet and profit.”

But progressive business and the sustainability movement can’t wait for government to catch up; they need to take action off their own bat. So where to begin?

With our ears, says Uren. “The signals were all there, but we weren’t listening properly. We need to do less articulating of what we think the problem is, and more going out and talking to people.” And the message that comes back is going to be different in different places, she adds. “What you need to do in London is different from what you need in the North; what you need in the Midwest is different from New York. Business needs to authentically connect with local communities, in ways it’s talked of doing before but has rarely done.”

Marks and Spencer goes local

One honourable exception in the UK, mentioned by several whom Ethical Corporation spoke to, is Marks and Spencer. The retailer has drawn plaudits for the depth and ambition of its Plan A initiative, led by its director of sustainable business, Mike Barry, who is a member of Ethical Corporation’s advisory board. He is one of the few who can claim to have spotted those signals before the 2016 earthquake.

“I’m not claiming foresight,” he says. “I never predicted Brexit. But about 18 months ago, we realised that something was happening. Something that risked business being seen as very remote from ordinary people’s lives.” And that applied to M&S’s sustainability work, too. “For 10 years, Plan A scored great successes in the fields of climate change, deforestation, oceans and so on,” says Barry. Now, he says, it’s making a significant shift – one which might just be a model for others to follow.

It’s going local. “We realised we had to make sustainability much more relevant to our customers in the communities in which they lived.” So each M&S store was charged with raising funds for nearby projects, with customers deciding how the money should be spent, donating surplus food to local charities, volunteering on community schemes, and so on… Its campaign, Spark Something Good, similarly put the emphasis on involving local people in local schemes.

But wait a minute. Isn’t there a danger this is just a reversion to the good/bad old days of corporate philanthropy – a wealthy patron bestowing his largesse on the grateful masses – rather than a grown-up sustainability strategy? Sally Uren doesn’t think so.

“This is a company asking, ‘Right, what assets do I have, and how do I use them in a way which drives resilient communities?” Others could follow the lead, and it means going way beyond traditional sponsorship, she argues. “So, rather than just give money to the local school, how about investing in a new classroom that can be used in the evening by community groups, and maybe by entrepreneurs in the school holidays? Look for ways to join forces with local agencies, philanthropic outfits, governments – develop a blended funder model which delivers real resilience rather than just a new football kit for the local team or whatever.”

Transformative technology

This approach doesn’t mean neglecting wider sustainability work, says M&S’s Barry. “It’s not an ‘either/or’. The sustainability journey is a million small things building up to a big whole.” The epitome of this approach is M&S’s Community Energy Fund, which aims to boost the take-up of renewable electricity at a local level.

The potential for local energy – particularly wind power – is huge across Europe and the States. It doesn’t take too great a leap of faith to imagine that the “local power for local people” angle might eventually win round some of the green movement’s least likely allies – the Ukip Brexiteers, the Trumpists. All the more so, perhaps, if it can be part of a local manufacturing renaissance – and that needn’t mean the smokestacks of old. The rise of 3D printing and similar local manufacturing and milling techniques holds out the tantalising prospect of decentralised industry powered by distributed, renewable energy.

Beneath all the hype, 3D printing is a potentially transformative technology. Sustainability expert John Elkington, now with Volans, enthuses over the rise of the FabLabs, the network of digital fabrication workshops, typically combining 3D printers with cutters and milling machines and IT design and assembly.

Woods of The Crowd makes the case for prioritising investment in this nascent economy in the “left behind” areas. “You could do worse than look at the Brexit vote map. Take it as a proxy for popular disillusionment, and ask: how do we get things moving there? Community energy creates electricity but it also creates community, and that’s what these places desperately need.”

They also need jobs. “We have to ask what are the skills we will need in the future that we don’t have today,” says Uren. “Business needs to start thinking ‘how do we invest to create the new renewable energy technologists, the new Blockchain experts, the guys who will go round fixing 3D printers?” She sees one point of light in Land Rover’s work investing in youth skills training around its base in the West Midlands.

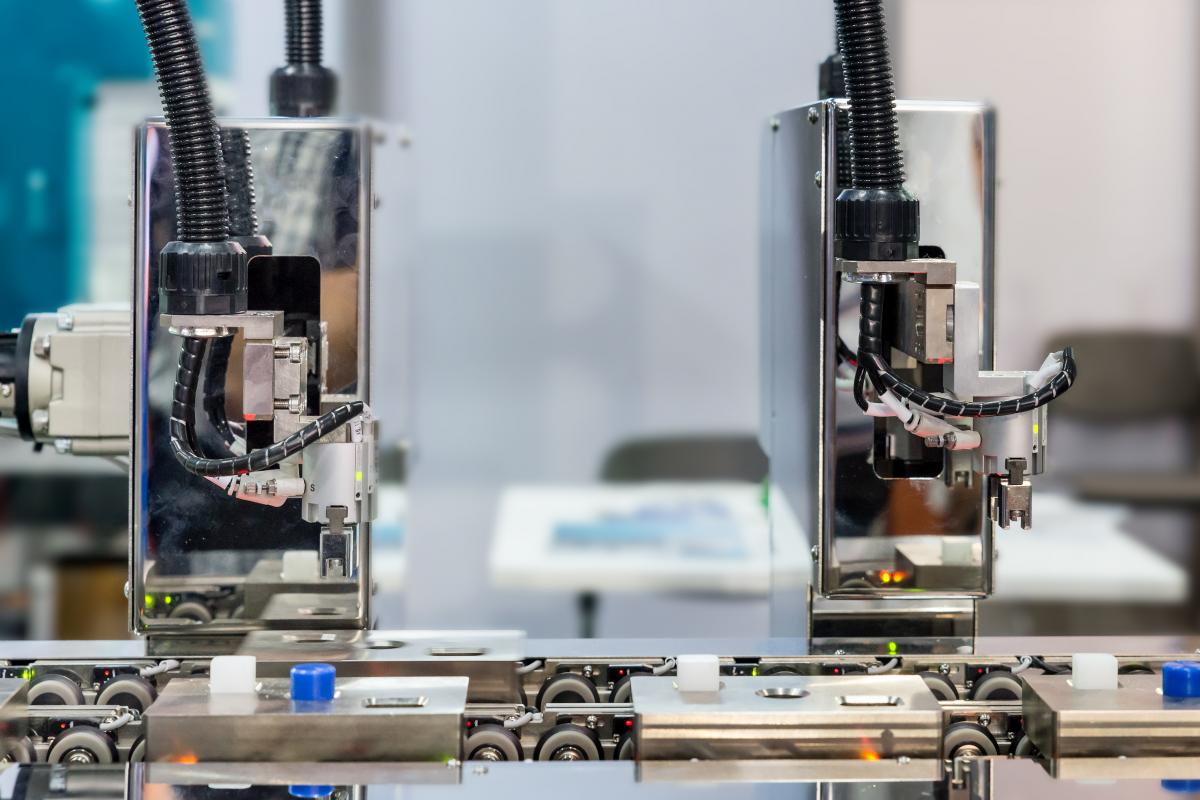

But just what jobs will be out there? As automation kicks in, whole swathes of employment will disappear, and it’s not remotely clear what might replace them. The trend is independent of economic cycles, so it won’t get better in a boom. Indeed, the good times are likely to drive more automation, not less. As Elkington observes: “There is a nexus of innovations coming together – AI, machine learning, robotisation, self-designing robots which learn down generations – you jump to such a different level of productivity and controllability”. He points to recent studies suggesting that almost half of current white collar jobs are at risk – let alone the blue collar ones, from coal miners to truck drivers, that are already teetering on the brink. “An old economic order is coming apart,” he concludes.

Uren is blunter. “Automation could be more damaging to society than climate change. And nobody is talking about it. We’re entering into another massive shift; we need to grab hold of that and start making some smart choices, rather than sleep-walk into a society that I don’t think anyone wants.”

Faced with this looming transformation, major corporates are strikingly shy of talking about it, fearing negative PR, says Elkington. Instead, “it’s the innovators who are at the forefront [of this shift], people like Deep Mind [Google’s AI arm], who are flagging up the need for someone to do some serious thinking on the implications of it all.”

Left-field solutions

One consequence could be an accelerated debate on the idea of a basic income, paid to all citizens, providing enough to live on irrespective of whether you have a job, or are entitled to particular benefits. It’s a simple solution, but one that could also be prohibitively expensive – though possibly less costly to society, ultimately, than having entire communities that are dependent on welfare because there is no prospect of jobs.

As Woods points out, the idea is gaining traction. Pilots are under way in various parts of the world, including Canada and the Netherlands. Elon Musk of Tesla is a fan, as is Obama, who predicts it’s 10 years away. Woods suggests government and business combine to stage pilots in some of the left behind areas of the UK.

Amidst the political upheaval caused by the Brexit vote, he says, now might be a good time to experiment with “some mad, left-field ideas. People voted for change, after all. They said the system isn’t working. So try new stuff. Mix it up.” As an example, he suggests a pilot in which business is excused from employment tax (in the form of national insurance contributions) in return for investing in local communities. “In an era of automation, robots go free and people get taxed. This is nuts!” It’s an echo of the sustainability world’s longstanding campaign to shift the fiscal burden from labour to resources: in other words, taxing what you don’t want (pollution) not what you do (jobs).

A basic income could even, potentially, be part of a new model of citizen engagement – one in which decision-making is devolved much more directly to local communities. After all, one of the key factors in the “roar of the left behind”, as Uren put it, has been their sense of disenfranchisement: of having little or no say in the decisions that affect them.

And it’s here that sustainable business might have a lot to contribute. After all, it pioneered the concept of “stakeholder dialogue”, of giving local people a say in developments that affect them. Many businesses are already rooted in communities to a greater extent than politicians. And bold new experiments like Marks and Spencer’s local initiatives show that there’s both an ability within companies, and an appetite among their customers, for real community engagement.

Business alone can’t be the answer, of course. Fixing the “broken society” will need radical reform in politics too. But it might help make a start.