A year of green shoots but few surprises: Oliver Balch provides an overview of corporate sustainability’s progress in Latin America during 2015

Latin America has never been at the forefront of corporate sustainability, but the region has made huge advances over the past decade or so. That’s all to the good. In the Amazon biome alone, which incorporates Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and, of course, Brazil, the continent is home to at least one 10th of the world’s known biodiversity and around 16% of the planet’s total river discharge into oceans.

Couple that with high biodiversity areas such as the Orinoco flooded forests, the Pantanal and the Atlantic Forests, and environmental conservation – including that by companies – has global ramifications. By the same token, the region’s success in tackling its most significant socio-economic and development challenges depend in no small part on the business practices of the corporate sector.

The private sector’s progress is evident in the network of business-led corporate responsibility groups that now stretch across the continent – organisations such as Instituto Ethos in Brazil, IntegraRSE in Central America, Acción RSE in Chile, Cemefi in Mexico and IARSE in Argentina.

Yet the traction of these organisations, and the enthusiasm of their corporate members, is not a given. Where sustainability sits on the corporate balance is strongly influenced by at least three contextual factors: business confidence, political direction and public pressure. And 2015 wasn’t an especially good year for any of these.

So what was the state of play in 2015? First, business confidence. For much of the past decade, Latin America’s economies have remained buoyant thanks to global demand for primary commodities – primarily mineral and metals (Chile, Colombia and Brazil, in particular), oil and gas (Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador) and agricultural cash crops (almost everywhere).

A relatively low exposure to international finance meant the region survived the worst of the 2008 global credit crunch. But the recent slowdown in the Chinese economy in particular hit the region’s economies hard. Add to that fears over interest rates in the US (a key trading partner for many Latin American countries), plus a prolonged question mark over emerging market stocks, and economically times were tough in 2015. What was a bad year for the region’s leading economies (Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile) was a terrible one for the region’s largest economy, Brazil, which endured its worst recession since 1990.

As well as low business confidence, 2015 brought precious little of the legislative ambition of recent years. No further adoptions of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, for example, as happened previously in Costa Rica. No extension of voluntary moratoria on deforestation in the Amazon, as per the now well-established case of Brazil’s soya industry. Venezuela, meanwhile, which controls the largest proven oil reserves in the world (at around 300bn barrels), wasn’t even able to muster a national action plan ahead of the Paris climate talks in December.

In fact, 2015 was the year a number of promising progressive policies began to stumble or unwind. Paraguay’s commitment to Social Progress Index has yet to make any meaningful advance. Others, such as Ecuador’s integration of environmental rights into its constitution, continue to go backwards (plans to drill for oil in the Yasuni National Park, in the Amazon, continue apace).

With commodity markets slowing and oil prices falling, the region’s governments have become significantly less flush. That meant a sharp slowdown in state-funded welfare programmes, job creation schemes and poverty reduction initiatives – all of which have been expanding over the recent past.

The public responded with understandable frustration, as evinced by street protests in Venezuela, Ecuador and elsewhere. Yet the historic state-led orientation of both economic management and social provision means few look to the private sector to step up to the plate and help out. Few companies do, therefore.

Instead, the oxygen of politics was consumed by more habitual preoccupations: corruption and poor administration. The most obvious example is Brazil, where president Dilma Rousseff looks set to face impeachment over dodgy accounting moves. The incident follows an ongoing corruption scandal that has engulfed Petrobras, Brazil’s state-run oil company and a cash cow for government coffers. More than $3bn has allegedly been siphoned out of the company over recent years.

The latest culprits to be embroiled in the case are leading lights from the region’s engineering sector, which stand accused of price-fixing and bribery related to the more than $10bn-worth of infrastructure investments for the 2016 Rio Olympics.

On the more positive side, big business and the investors that finance them will take heart from the swing to the political right in recent elections. The 17-year strangle-hold of “chavista” petrodollar socialism in Venezuela looks set to weaken after December elections. The left-wing Peronist Party’s grip on power in Argentina also ended in November.

Both results hold out the promise of more orthodox economic and trade policies in the year ahead. The outcome should be greater investor confidence and longer-term policy stability, as has unfolded in countries such as Peru and Colombia in recent years. That bodes well for progressive business.

Lastly, public opinion appears to be shifting. Since the global recession of 2008, pressure on companies to take a more proactive role on social and environmental issue has begun to slip. According to the latest Corporate Sustainability Radar study, carried out by research firms GlobeScan and Brazil-based Market Analysis, 56% of Latin American adults think issues such as respect for human rights and helping solve poverty are key to a company being sustainable. That’s down from 60% in 2007.

Equally importantly, the order of priorities has changed. Whereas pro-environmental performance was considered the number one responsibility in 2007, treatment of employees is now the top concern. And the demand for companies to be environmentally friendly has declined by 8.4% since the 2008 crash.

“These lower pressures on companies apparently reflect a fatigue and increasing disconnect with corporate sustainability as a model to aspire and an effective and authentic policy proposal,” says Fabián Echegaray, managing director of Market Analysis.

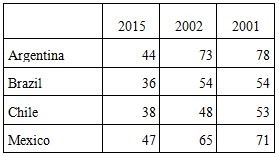

By way of example, he points to the number of people discussing companies’ ethical behaviour, which, according to Corporate Sustainability Radar, has fallen drastically in the region’s key markets (see Table 1).

*Over the past year, how frequently, if at all, have you discussed the ethical or social behaviour of companies with your friends or family members? (% many times + few times)

Source: Corporate Sustainability Radar study by GlobeScan/Market Analysis

This doesn’t mean that consumers or the public at large have lost interest in sustainability issues. The difference now is that, Echegaray argues, “Latin Americans are no longer betting all their hopes on company actions as the appropriate response”. Social enterprises, charities and individual initiatives: these are where popular confidence for change now resides.

Usual suspects

The macro conditions may not be favourable, but that doesn’t mean Latin America’s corporate sector is inactive on the sustainability agenda. A number of significant initiatives are in place and continued to tick over during 2015. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Peru, for example, are all active participants in the OECD Working Party on Responsible Business Conduct.

Costa Rica, the region’s newest signatory to the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, is moving forward on a range of accountability and governance measures in order to obtain full OECD membership. Colombia, meanwhile, continues to promote the OECD’s conflict minerals’ guidelines across its gold mining industry.

The Global Reporting Initiative, which boasts formal national networks in Brazil and Colombia, has shown “notable eagerness” to address transparency around sustainability challenges, according to the UN-backed initiative. Brazil is widely seen to be leading the pack in terms of reporting. According to the latest Corporate Sustainability Index from BM&F Bovespa, the Brazilian stock exchange, every sustainability report published by a listed company was in accordance with GRI directives this year. This compared with 7% the previous year.

The Bovespa data reveals a willingnessof companies to sign up to public commitments. More than nine in 10 of Brazilian listed companies declare a corporate policy on climate change, for example. Yet nearly half have failed to achieve their greenhouse gas emissions targets. Similarly, only 44% factor sustainability issues into management appraisal or remuneration. What’s true for Brazil is equally true for the rest of the region, if not more so.

The UN Global Compact is following a similar vein: high interest, questionable impact. In 2015, participation in the UN’s benchmark responsible business initiative expanded yet again, with Latin America and the Caribbean now counting the most members of any region after Europe. Much of the focus of the region’s 17 country-based networks over the past 12 months concentrated on how to shape and implement future solutions in light of the new Sustainable Development Goals.

For other key players in the region, 2015 appears to have been a quiet year. In November, the Inter American Development Bank announced a $20m “Opportunity Facility” to support loans to housing developments, agricultural co-operatives and other innovators at the bottom of the economic pyramid. However, the multilateral lender’s list of approved project highlights for corporate social responsibility in 2015 is empty.

The World Bank had a slightly more active 2015. In September, for instance, it laid out the details of a $700m project to promote “green growth reform” in Colombia, while in July it unveiled an $80m loan initiative to support “climate-smart” water use among Ecuadorian small and medium-sized farmers. Bilaterally, meanwhile, the European Union has been working with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States to promote national CSR action plans.

As for individual corporations, the leaders are still the leaders. Among Latin American-based multinationals (so-called “multilatinas”), CSR rankings and industry awards continue to feature the likes of cement maker Cemex (see box) and supermarket Bimbo in Mexico, Colombian coffee chain Juan Valdes, Brazilian cosmetics brand Natura and bank Itaú Unibanco, and Argentina-based food firm Arcor, among others.

Cemex: Changing the World

Cemex has been a stalwart of sustainability rankings in Latin America ever since such indices began. And 2015 was no exception for the company. In August, the Mexico-based cement manufacturer found its way onto Fortune’s Change the World list. The all-star ranking recognises 50 companies worldwide that have made a “sizeable impact” on major global social or environmental problems.

The only Latin-American based company to be included, Cemex (16th place) was selected for its “Patrimonio Hoy” programme. Initiated in 1998, the initiative provides low-income families living in urban and semi-urban areas with construction materials at competitive prices so they can build their own homes. In addition, the programme’s beneficiaries receive micro-finance, technical advice and logistical support from community-based promoters – many of whom are women. The initiative operates through more than 100 local offices in Mexico, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic

Since its inception, Patrimonio Hoy has provided affordable solutions to more than 2.5 million people throughout Latin America. Participants are able to build their homes or extensions three times faster and at a third of the average cost to build a home in Mexico. The houses are also valued at around 30% above average because of the higher quality and functionality of the structures. Since inception, Patrimonio Hoy has advanced more than $290m in microcredits to low-income home-builders. Local building materials distributors, meanwhile, generate sales of more than $30m a year through the programme.

Over the years, Cemex has developed a raft of other innovative housing-related programmes. The list includes ConstruApoyo, focused on rebuilding after natural disasters; Lazos Familiares, which assists communities in rebuilding and renovating community institutions and buildings; and Mejora tu Calle, an initiative designed to provide cement for neighbourhood streets and pavements.

Similarly, North American and European firms with a high exposure and long trajectory in the region dominate the sustainability best-practice lists. Think Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Telefónica, McDonald’s, Microsoft, BBVA, Santander and Diageo.

Foreign mining companies such as Newmont, Anglo American and GoldCorp have probably, through their subsidiaries, invested more than any other sector in community development and environmental initiatives. Yet their activities continued to be controversial. Even before the catastrophic Samarco mine burst in November (a project co-owned by Australia’s BHP and Brazil’s Vale), six people died in mining-related clashes in Peru – where social conflicts and red tape have cost the country $14.9bn in lost revenue exports between 2010 and 2014, according to the Peruvian Institute of Economics.

Even among the region’s corporate leaders, collaboration across industry remains rare. In the shape of the New Employment Opportunities alliance, however, 2015 provided proof of how effective collective approaches can be. The alliance is a cross-sector initiative aimed at providing job opportunities for one million young people from poor and vulnerable backgrounds by 2022. In just three years, more than 2,000 companies in 16 countries have lent their support to the scheme, representing an investment of around $80m.

Spearheaded by the Inter-American Development Bank, along with a cohort of corporations – Arcos Dorados, Caterpillar, Cemex, Microsoft and Walmart – the initiative expanded into six new markets this year, including Brazil, Chile and Uruguay. The alliance’s current tranche of projects will, once completed, provide employability services to a projected 382,000 youth.

What turned out to be an “autopilot” year for corporate-led sustainability efforts, as one leading expert puts it, proved to be a full-throttle year for the social enterprise. Testament to that is the growth of the “B Corp” movement – a global network of businesses committed to holistic stakeholder benefits (not just shareholder returns).

Initially conceived in the US, the B Corp certification arrived in Latin America a couple of years ago (where it’s branded Sistema B). The region now counts 192 certified companies, most of which are clustered in four countries: Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Chile. The vast majority are small, nimble firms with innovative business models designed to address the region’s biggest social and environmental issues, from unemployment and inequality to resource efficiency and energy security.

Latin America’s record on corporate sustainability has been safe and steady to date, and 2015 didn’t buck that trend. What the region could really do with is more nuance, ambition and innovation. For inspiration, the region’s biggest businesses could do to tap into the energy and creativity of the emerging crop of ethically minded minnows at the grassroots.

corporate sustainability environmental conservation corporate responsibility groups sustainability economy OECD guidelines environmental sustainable environmentally friendly CSR energy