UK wind subsidy shift raises repowering hopes

The planned inclusion of onshore wind in UK subsidy auctions boosts the business case for repowering, but uptake may be slow as planning hurdles nobble projects in England and operators squeeze out income from existing assets.

Related Articles

From next year, UK onshore wind developers will be able to bid for government subsidies, ending a five-year moratorium on price support. Under government plans, onshore wind and solar will compete for contracts for difference (CfDs), boosting the business case for greenfield and repowering projects.

Wind and solar costs have fallen significantly in recent years and made them competitive with conventional power generation. In August, the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) recommended increasing the UK's renewable energy target for 2030 from 50% to 65%, based on "the falling cost of renewable electricity technologies and the relative speed with which they have proven to be built."

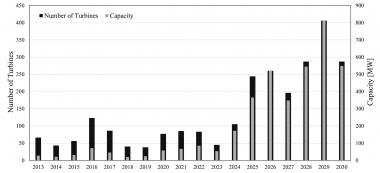

The UK has 12 GW of onshore wind capacity and the number of turbines reaching their design life of 20 years will rise sharply in the coming years. Owners must decide between repowering, extending the lifespan of the existing technology, or decommissioning the facility.

Onshore UK wind capacity reaching 20 yrs

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: 'A decision support tool to assist with lifetime extension of wind turbines' by Ruberta, McMillana, Niewczas. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. (May 2018).

Some 1.2 GW of new UK onshore wind repowering capacity is under development, five times the current repowered capacity, industry group RenewableUK said November 3. Around 180 MW of repowering projects could potentially bid in the 2021 CFD auction, a spokesperson for RenewableUK, told Reuters Events.

The price support offered by CFDs will boost demand for onshore wind repowering, David McMillan, Senior Lecturer at the University of Strathclyde, said.

“Particularly important will be the level of insulation from negative prices," McMillan said.

Across Europe, growth in renewable energy capacity is increasing the frequency of low or negative half-hourly prices at times of excess supply. The impact of oversupply was further amplified in the spring when COVID-19 lockdowns sliced demand.

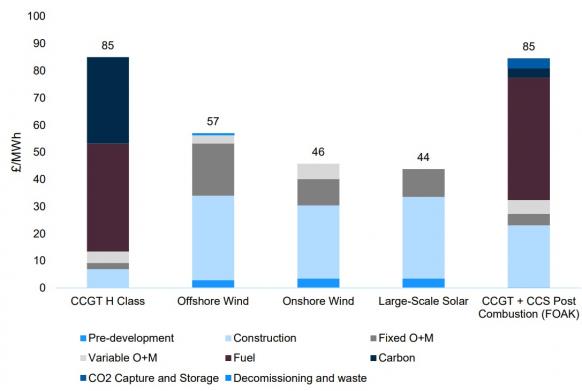

Onshore wind costs have fallen dramatically since UK subsidies were scrapped in 2016 and these projects should be competitive against other generation types, McMillan noted.

Planning applications remain a key hurdle for repowering projects, and many projects will not be ready to participate in next year's auction. Demand for repowering should pick up in subsequent years as more turbines approach 20 years of operations.

Some 20 UK onshore wind projects for a total capacity of 665 MW have applied for extensions and repowering, mostly located in Scotland, according to research group Cornwall Insight.

"Overall, more favourable planning restrictions [for developers] in Scotland will likely lead to more projects north of the border," McMillan said.

Planning pressures

Repowering allows operators to install larger turbines with greater efficiency but greater tip height and noise production create fresh permitting challenges.

Installers of larger units must consider the impact on radar systems, as well as the landscape, and applications can take as long as greenfield projects, Jeremy Sainsbury, Managing Director at Natural Power, a project consultancy, told Reuters Events.

Without complications, planning consent can be achieved within three years but if issues are raised it can take five or six years, he said.

In December 2019, the Scottish government approved the repowering of SSE Renewables’ Tangy wind farm on the Kintyre Peninsula in western Scotland. SEE plans to replace 22 turbines of total capacity 18.7 MW, online since 2003, with 16 turbines of capacity up to 80 MW capacity. Tip height would increase from 130 MW to 149.9 MW.

SSE said it would consider the options for route to market ahead of taking a final investment decision. The company declined to give further detail for this article.

The real impact of new CFD support for onshore wind repowering will more likely be seen in auctions held towards the end of the decade, as operators will need to gain planning permission in advance and many will wait for additional revenues from the UK's renewable obligation certificate (ROC) scheme to end.

ROCs provide 20 years of additional revenue to developers and are sold to power suppliers. The UK government ended the scheme in 2017, meaning incentives would remain in place until up to 2037, depending on the commercial start date of the asset.

Many of the projects in the current UK repowering pipeline are likely to be older projects of turbine capacity below 2 MW, which will stop receiving ROCs in 2027, Sainsbury said.

Between 2027 and 2030, around 3.6 GW of onshore wind assets will stop receiving ROCs, according to Cornwall Insight.

Subsidy battle

Contracts for difference (CFDs) have helped the UK become a world leader in offshore wind energy. The UK has installed over 10 GW of offshore wind capacity and aims to quadruple capacity to 40 GW by 2030.

Offshore wind costs have plummeted on technology advances and economies of scale, but costs remain higher than onshore wind and require greater initial capital outlay.

Forecast UK generation costs by technology in 2025

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: UK Government Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, August 2020.

Under the government's plans, onshore wind will compete against solar for CfDs while offshore wind will compete against less mature technologies.

UK solar activity is also on the rise and costs are falling. Large operators like EDF are partnering with local experts and coupling solar projects with batteries to reduce intermittency risk and access higher market prices.

Longer lifespans

The benefits of repowering depend on a number of technological and site-specific factors. In the absence of price support, UK operators have typically preferred to extend the lifespan of existing assets rather than replace with higher capacity turbines.

The cost of maintaining existing assets versus new units is also a key factor. For older projects, operators must weigh growing component failure risks and insurance premiums against potential power revenues.

Operations and maintenance (O&M) practices have improved significantly in recent years, providing operators with a clearer view of plant performance.

Many turbines are lasting longer than originally expected which has dented, or at least postponed, demand for full repowering, Sainsbury said.

“People are looking at life extensions at 10-12 years of age but you would only look at repowering at 25 years,” he said.

Reporting by Neil Ford

Editing by Robin Sayles