US urges haste on domestic HALEU plan as Russia faces isolation

The United States must urgently launch a comprehensive plan to produce industrial quantities of high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) as closing supply chains from Russia leave the U.S.’s advanced reactor program in danger, say industry leaders.

Related Articles

Today, about 20% of U.S. low-enriched uranium (LEU), enriched to below 5% and used by U.S. light water reactors (LWR), comes from one of the world’s major suppliers of global uranium and nuclear fuel, and subsidiary of state-owned Rosatom, Russia’s Tenex.

HALEU can also be purchased on international markets from Tenex in both oxide and metal form as needed.

Domestic U.S. uranium enrichment capacity fell to nothing in 2015 from 27.3 million Separative Work Units (SWU, used to measure the amount of work done to enrich uranium) a year in 1985 just as U.S. utility requirements doubled to 15 million SWU/year, according to figures by Centrus and U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The only current uranium enrichment capability in the United States is in Urenco's New Mexico plant, with a capacity of some 4.7 million SWU/yr in 2020, according to World Nuclear Association figures.

Meanwhile, enriched uranium capacity in Russia has risen to 28.7 million SWUs a year in 2020 from just 3 million SWUs in 1985.

While Russia, which is facing international isolation after its invasion of neighboring Ukraine, produced just 6% of global uranium in 2020, Kazakhstan, which produced 41%, moves about half of their uranium supply through Russia, Co-founder of Good Energy Collective Jessica Lovering noted in a twitter thread.

As advanced reactors move closer to operation, the need for HALEU will ramp up considerably.

“There is essentially no choice for advanced reactor developers but to initially rely upon Russian-supplied HALEU, particularly given the expedited timeframes for their first demonstrations and units,” Third Way said in the study ‘Background and Policy Issues – HALEU Fuel Supply.’

Nine out of ten reactors funded by the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP) will need HALEU to run and, as wide-ranging sanctions descend on Russia, those working on the next generation of nuclear reactors are growing concerned over the West’s over-reliance on Russian nuclear technology and fuel.

“This is an urgent matter, and we need to deal with it quickly. Congress and the DOE need to take it on urgently,” said Senior Technical Advisor at the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) Everett Redmond.

As calls grow for the move to net zero, nuclear was finally being seriously considered as part of the energy mix, but cutting-edge technology in the sector would not thrive without HALEU, association and company heads agreed during an American Nuclear Society (ANS) webinar “High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium: Fueling Nuclear Energy’s Future.”

“We, in the advanced reactor community, have a great opportunity here. Companies that hadn’t been talking about nuclear are talking about nuclear. The opportunities are arising, but we have to have fuel,” Redmond said.

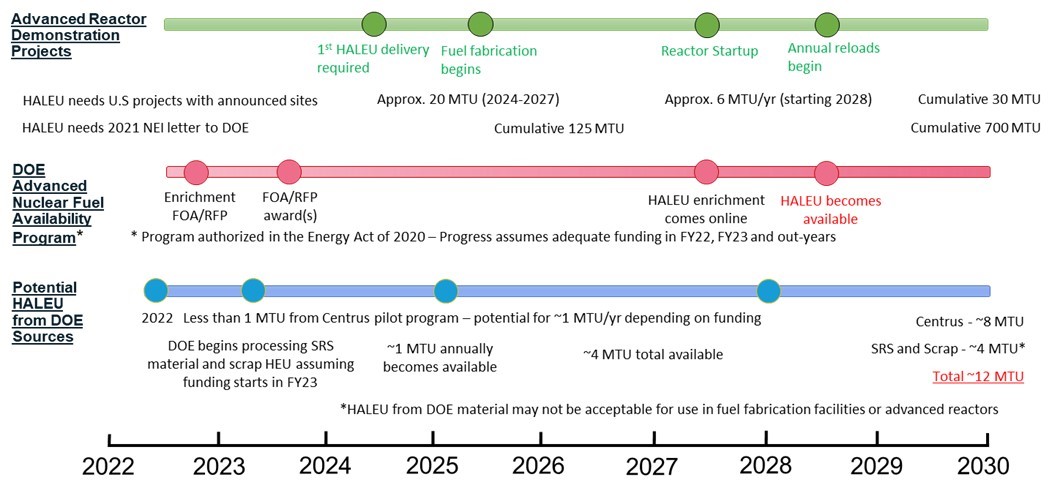

A Comparison of Timelines for Industry and Potential Supply of HALEU from U.S. Sources

Source: Nuclear Energy Institute white paper: "Establishing a High Assay Low Enriched Uranium Infrastructure for Advanced Reactors"

What’s needed

To run new, advanced reactors, especially micro and very small modular reactors, the uranium must be enriched to as much as 20% (HALEU), compared to the around 5% used by most of the world’s reactors today.

The NEI estimates that approximately 20 metric tons (MTU) of HALEU will be needed between 2024 and 2027 for the first reactor cores to support the projects in the United States that have publicly announced a site. Another 6 MTU a year will be required from 2028 to support reloads for these reactors.

These estimates, however, are based only on reactor projects that have publicly announced a site. Cumulative HALEU needs to support future projects is higher, with 125 MTU needed by 2026 and 700 MTU by 2030, NEI told the U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm in a letter in December.

Meanwhile, stocks are low.

The DOE is currently processing spent Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II) driver fuel to recover enriched uranium and downblend it to just under 20% and a total of around 10 MTU will be available from that, 5 MTU by 2025 and the rest by 2028.

Savannah River Site has high enriched uranium in storage which may be processed, assuming it receives the appropriate funding, to produce around 1-2 MTU a year within a couple of years. Another 1 MTU per year, also provided Congress agrees on funding, could be gleaned from processing spent fuel at Idaho National Laboratory (INL).

X-Energy, one of the winners of the ARDP, says it needs 3 MTU of uranium in HALEU form and oxide form at 15.5% enrichment some two years in advance of the reactor starting up on the grid, or around the end of 2024 or early 2025. Its demonstration reactor will then need another 3 MTU the following year and reloads of 1.9 MTU going forward.

What’s available

To some extent, Congress is hearing the calls to ramp up spending for HALEU production. Early in March this year, the Fiscal Year 2022 Omnibus appropriations bill included $45 million for the HALEU program.

While well received, the ANS has called for funding closer to $200 million a year.

“Haleu fuel supplies is very critical issue that needs to be addressed sooner rather than later. I’ve heard from several in the advance reactor community that Russian HALEU is not the best business case and I’ve heard those comments going back to, in some cases, over a year ago. In my view, this unprovoked attack only heightens this conversation,” said Senior Director of Government Relations BWX Technologies Scott Kopple during the ANS event.

There are currently four HALEU enrichment options in the United States.

Urenco operates the only licensed enrichment facility in the United States, for 5.5% enriched uranium, though it has applied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to increase those limits to 10% assuming the necessary funding and/or offtake commitments.

Centrus, the only company in the United States licensed to enrich uranium up to 20%, has a demonstration project to produce up to 1 MTU of HALEU before it ends later this year. The company has said that 12 MTU a year capacity could be brought online within four years of securing funding and/or offtake commitments.

Global Laser Enrichment (GLE) has an NRC license for a full-scale enrichment facility, but that is yet to be built, while Orano, previously AREVA, also holds a license but has requested it be terminated due to market conditions.

A NRC license for a new enrichment facility or to modify an existing facility to produce HALEU would take anything from 24-36 months, according to NEI.

The capacity and technology to produce the required amount of HALEU for the next generation of advanced reactors within the United States and bypass Russian imports is within reach but, as with so much within nuclear power, it will require political will and deep pockets.

“This is a solvable problem. This is something that we have the technology, we have experience producing this material, and it’s just a matter of making the commitment and making the prioritization to actually see this through,” said Project Manager for Nuclear Innovation Alliance Patrick White.

By Paul Day