US nuclear investment expected to soar after DFC ban lifted

The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) is expected to agree to lift a ban on investment into advanced nuclear energy projects for export in July, opening the floodgates to potentially billions of dollars of overseas spending.

Related Articles

The DFC is likely to decide to lift the ban after the end of a 30-day public notice and comment period which began June 10 in a move that industry experts say will boost U.S. influence in the global nuclear sector but critics claim will undermine efforts to stem proliferation of dangerous and unstable materials.

“Modernizing DFC’s policy to offer financing for nuclear projects supports the agency’s development mandate, bolsters U.S. foreign policy, and recognizes advances in technology which could make nuclear energy particularly impactful in emerging markets,” the DFC said when opening the public notice.

The state-run development bank has a total investment limit of $60 billion and supports projects in emerging markets through equity financing, debt financing, political risk insurance and technical development.

Like its predecessor, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, the DFC has been prohibited from investing in nuclear projects and the announcement that this will change as part of the current administration’s efforts to support the U.S. nuclear industry has been well received.

“I think it’s a huge step forward ... it’s very, very significant,” the Nuclear Energy Institute’s President and CEO Maria Korsnick said when asked about the move during a recent webcast.

The change would pressure other investment vehicles, such as the World Bank, to also reconsidered their own restrictions, Korsnick noted adding that the appearance of small modular reactors and micro reactors would mean investments would not need to be of the full-scale gigawatt variety.

Energy Diplomacy

A lack of state financing is just one of the reasons that the U.S. global influence in civil nuclear projects has waned over recent decades, leaving a vacuum for other state players such as China and Russia.

“China has a much different commitment to nuclear proliferation than the United States and Russia uses its nuclear program as an element of its energy diplomacy, which is a pretty aggressive diplomacy as we’ve seen in the way it’s used its pipeline network to influence politics in Eastern Europe,” says Executive Director at ClearPath, a D.C.-based think tank dedicated to clean energy innovation, Rich Powell.

Financing the development of nuclear power in a country is the start of a long-term bilateral relationship, including ten years to site, permit and build a reactor which could run up to 80 years before a 10-year decommissioning process, says Powell.

“So that’s a century-long commercial relationship that you’re starting up with a country and that's a lot of trade, services and bilateral economic leverage.”

The United States would take with it the 123 Agreement from the Atomic Energy Act which establishes the ground rules and strict standards to follow with nuclear cooperation between the United States and another country, standards that are not necessarily enforced by China or Russia.

“We have to start with the base understanding that many, many more countries than we realise are interested in nuclear and are going to get it, and the question is who is going to give it to them?” asks Jennifer Gordon, managing editor and senior fellow at the think tank Atlantic Council.

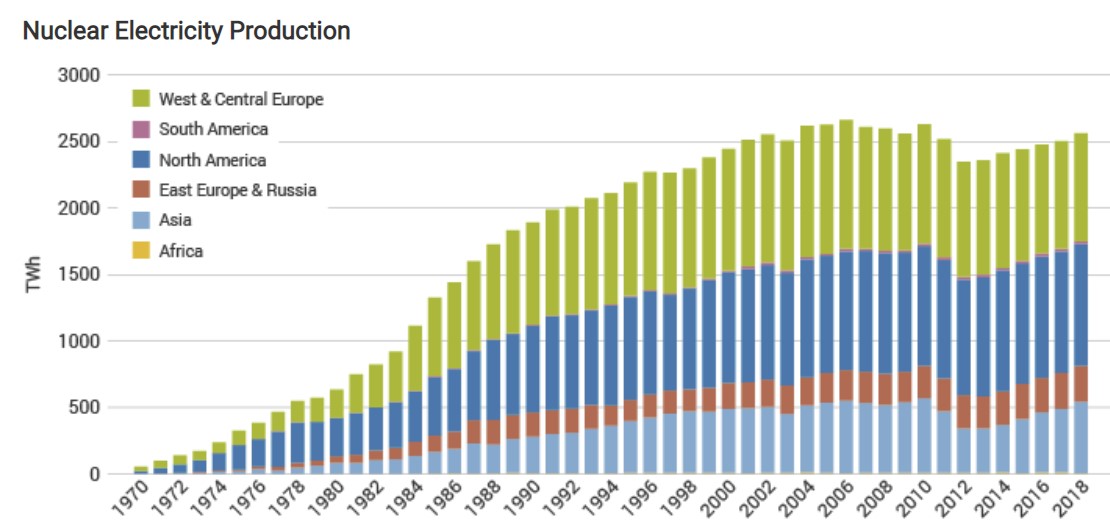

(Source: World Nuclear Association and IAEA Power Reactor Information Service)

Overlooking the Risks

The lobbyists pushing for the DFC to loosen its purse strings to countries with budding nuclear ambitions are bowing to a struggling industry and overlooking the risks, say critics of the move.

The nuclear industry has failed to expand in the United States due to cheap natural gas and the falling costs of renewable energy technology and so it is seeking a new revenue source abroad, says Director of Nuclear Power Safety for the Union of Concerned Scientists Edwin Lyman.

The main problem would be the kind of less developed, poor countries the DFC is likely to focus on, says Lyman.

“If you’re exporting nuclear energy to countries with an independent nuclear authority that has the expertise, that’s one thing, but if you’re marketing reactors to less developed nations that don’t have that experience without working with them first to make sure that they do, it’s a recipe for disaster,” he says.

Target countries may lack emergency preparedness infrastructure that can deal with terrorist threats or accidents or prevent proliferation, he says, especially when dealing with new advanced reactors such as small modular reactors and micro reactors, which are seen as the most likely to receive funding.

“Developing a novel technology without an established supply chain, without the codes and standards in place, without experience in the design or the materials or the operation, to just say you can put that together in a couple of years and sell it around the world just does not comport with reality,” he warns.

However, proponents believe that the concerns are mostly unfounded and the focus should be keeping the industry within the U.S. orbit that would protect it from failures and abuse by less conscientious actors.

“The Russians don’t care about non-proliferation and neither do the Chinese, and we do. We make countries sign an agreement which requires safeguards against proliferation or we won’t deal with them commercially in the nuclear field,” says Executive Chairman of Lightbridge Corporation USA Ambassador Thomas Graham, Jr.

“It would be a grave mistake to allow those two irredeemable dictatorships to end up dominating the world in commercial nuclear power. This change can very much help avoid that,” he says.

By Paul Day