U.S. developers find their own paths through regulatory maze

Advanced reactor developers in the United States are finding the licensing experience varies widely depending on the size of the reactor and the business model they are following.

Related Articles

One size does not fit all when licensing advanced reactors, with small modular reactor (SMR) developers such as NuScale looking to sell the VOYGR SMR to a third party facing different regulatory challenges than Oklo, where the company will play a part in their microreactor Aurora’s entire life cycle.

Both companies have travelled a long way along the exhaustive (and often expensive) regulatory path.

In February, The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) officially certified NuScale’s SMR design, the first SMR design certified by the regulator and just the seventh reactor design cleared for use in the United States.

Previous NRC-approved designs were larger reactors and include General Electric’s Advanced Boiling Water Reactor; Westinghouse Electric Company’s System 80+, AP600, and AP1000; GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy’s Economic Simplified Boiling Water Reactor; and Korea Electric Power Corporation’s APR1400.

Meanwhile, microreactor developer Oklo is working on the re-filing of its own combined construction and operating license application (COLA) for its Aurora reactor with the NRC, the first of its kind for an advanced non-Light Water Reactor (LWR) to be accepted for NRC review.

Different routes

NuScale’s VOYGR SMR, which can house up to 12 factory-built 50 MW power modules, is a very different machine than Oklo’s 1.5 MWe Aurora powerhouse and that difference, to some extent, is reflected in the companies' experiences with the regulator.

Pre-application activities with the NRC for the NuScale began in 2008 then, through a cost-sharing agreement with the Department of Energy (DOE), licensing activities started in 2013.

The long road to the NRC accepting NuScale’s Design Certification Application (DCA) for VOYGR SMR was completed in December 2016, submitted to the NRC in January, and accepted for review in March 2017.

The NRC issued its final technical review in August 2020 before voting to certify the design on July 29, 2022.

NuScale spent over $500 million, with the backing of majority investor Fluor, and over 2 million labor hours to develop the information needed to prepare its DCA, explains Vice President of Marketing and Communications for NuScale Power Diane Hughes.

Oklo, meanwhile, began pre-application engagements in 2016 before a Combined Operating License Application (COLA) application began in early 2020.

It was the first ever COLA for an advanced non-LWR design, the first developed entirely from private funding, the first submitted completely online, and was the first COLA application for an advanced fission technology to be accepted for NRC review in 2021.

It was also twenty times shorter and considerably less costly than previous COLA applications, the company says.

Founders of the microreactor Aurora powerhouse, which will be constructed and operated by Oklo, saw the COLA as a more direct route to full licensing given their business model of building and operating their plants.

“We’re a very small design and relatively simple, and it made sense for us to go straight to combined license including the design information, so all in one, since the COLA can include design,” says Oklo co-founder and Chief Operating Officer Caroline Cochran.

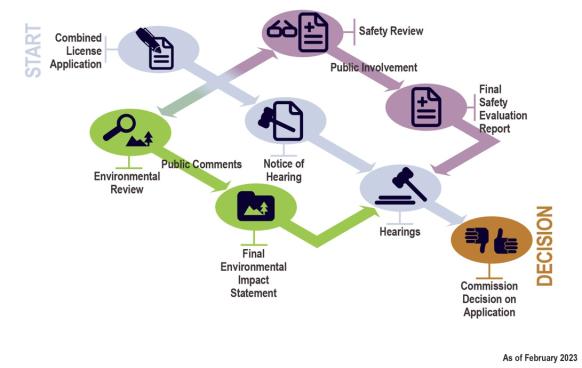

10 CFR Part 52 - Combined License Application Review Process

(Click to enlarge)

Source: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC)

Moving parts

Both companies opted for the NRC’s 10 CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) Part 52 process, introduced in the nineties as an alternative to the previous 10 CFR Part 50 process which has been used to license all the current fleet of reactors in the United States.

“NuScale elected to utilize the NRC’s 10 CFR Part 52 Process to receive the necessary operating, construction, and licensing permits for the CFPP (Carbon Free Power Project) based on the ability of the Part 52 Process to reduce the financial and schedule risks of building nuclear reactors,” NuScale’s Hughes says.

The CFPP will be NuScale’s first SMR to begin operation in the United States at the DOE’s Idaho National Laboratory and is expected to provide electricity to the Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS).

Since NuScale will not operate their own plant, their focus is on licensing its design, while construction and operation, covered as a single-step process under COLA, is left to its customers.

The Part 52 process requires two components to be satisfied before construction begins, with NuScale submitting the Standard Design Approval (SDA) application, and its customer, UAMPS, required to submit the COLA.

As a developer, NuScale’s SDA covers everything under the design that is not site specific, while the COLA includes site specific information and will be subject to an environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), as well as a safety review of operational issues including water, seismic, transmission, workforce, security, and emergency preparedness.

Under the schedule, the UAMPS COLA is expected to be submitted to the NRC in 2024, the review expected to be completed in 2026, and construction of the project is to begin shortly thereafter, Hughes says.

Oklo’s founders have opted to go straight to the COLA to cover both construction and operation of the plant in one regulatory swoop.

The company’s application was denied, without prejudice, in January 2022 for lack of information, but its founders are confident, after reaching resolutions with the NRC in December 2022, that they have a clear path to alignment with the regulator.

Time to evolve

For both developers, the lengthy licensing process has not stood in the way of technological advancement, and their original designs, deep in the licensing process, have evolved since the first application.

In the midst of NuScale’s licensing efforts, the company found that its technology could generate 25% more power per module, or 77 MWe each.

As such, the company is now seeking approval for its VOYGR-6, six-module configuration instead of the 12-module configuration and, since the uprated design is largely unchanged from the previous iteration, NuScale expects the NRC approval of the second SDA in 2024.

Oklo, meanwhile, has found that its reactor can generate up to 15MW out of the same amount of fuel and plans to submit an application for the uprating.

While technology advancements move faster than the regulator’s licensing schedule, the developers are optimistic the whole process will not have to be started from scratch, just the latest challenge for a regulator working to adapt.

By Paul Day