Tech advances make drones a must-have for nuclear operators

Technical advances in Unmanned Ariel and Ground Vehicles (UAV or UGV) mean they have quickly become a must-have piece of kit for the nuclear industry.

Related Articles

UAVs have been used for over a decade for difficult and dangerous jobs within and around a nuclear plant but more sophisticated and higher-resolution imaging, increased autonomy, longer battery life, lower prices, and even attached Geiger counters, mean drones are changing how even the most basic operations and maintenance job is conducted.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) first came upon the benefits of having a small, remotely operable vehicle that can carry measuring equipment after it was invited to Fukushima Prefecture in Japan to take readings following the nuclear power plant accident in 2011.

“We’d been offering the Fukushima Prefecture support to develop a technology which would allow post-accident monitoring to areas which might be difficult to access on foot. At that time, it wasn’t a mature technology, and this was a push to put in some resources and develop that technology,” says the Head of the IAEA’s Physics Section Danas Ridikas.

Precise radiation monitoring up until that point had been carried out by a worker with a radiation detection meter in a backpack walking back and forth over a suspected contaminated area before returning to base and examining the results.

The IAEA team first ran the drone in areas surrounding the plant that were accessible to both the backpacked worker and the UAV to validate the technology and measuremnet methodology. Soon, the drone was sent on its own mission to an area considered impractical for anyone to walk on.

That first visit showed how the drone could work and laid the path for what was to come.

“It’s like day and night between 10 years ago and now. We could make flights only with the dose meter or gamma spectrum meter or a camera, so if you wanted to do that in detail, you need to make three different flights. And the battery only lasted 15 minutes before it needed charging again or replacing by a spare set,” says Ridikas.

Now, all three devices can be fitted to one drone, the battery goes for more than half an hour and Ridikas’ team is testing a drone that can hold a device that measures both doses and gamma spectrometry.

Semi-autonomy, obstacle avoidance and full GPS which measures altitude as well as location are all on the cards.

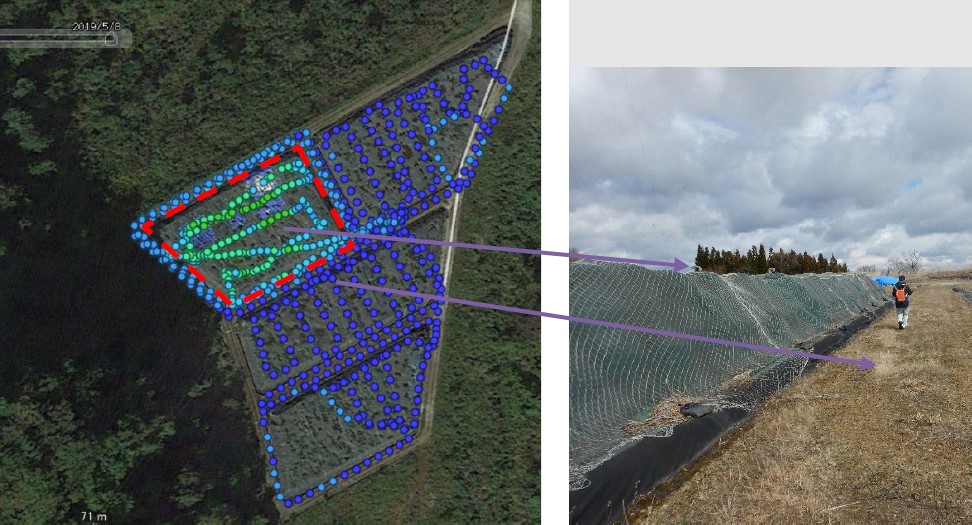

IAEA Unmanned Ariel Vehicle (marked within red rectangle) and backpack based radiological mapping at temporary storage site in Fukushima Prefecture

(Source: Fukushima Prefecture, IAEA)

On the market

Flyability, a private drone company based in Switzerland with offices in the United States and China, sells its UAVs at the starting price of $35,000, though this has immediately translated into savings for its customers, says Flyability Content Marketing Manager Zacc Dukowitz.

Their Elios 2 UAV, for the moment, carries only a camera with visual and thermal sensors, but this scaled down version of the IAEA’s machine has quickly become a must have for infrastructure companies, not least in the nuclear industry.

Its design, with the drone suspended in a spherical cage to protect it from collisions, has been specifically designed to fly indoors.

“Some people look at the price point and ask if we really need that tool, even though we’ve gone into their facility and done a mission that’s saved them $300,000 in one flight because of the cost of setting up scaffolding, the downtime to put the scaffolding up and take it down, not to mention improved safety and labor concerns,” says Dukowitz.

“Adoption can be slow in some industries even though the benefits have been demonstrated several times,” he adds, noting that the company now has drones at 65% of all nuclear reactors in the United States.

The idea for Flyability’s technology was also inspired by the nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi plant after the company's founders watched the sea wash away other ground-based robotics that had been brought to the site.

“Our founders realized that to be able to fly into a tight space and show you what was happening, drones could be a real benefit,” says Dukowitz.

Exelon Clearsight used Flyability’s Elios 2 to perform a drone-based inspection of a nuclear site’s containment building, a dome with over 39,000 square feet (3,623 square meters) of surface area to be inspected closely per the ASME Section XI IWL standard.

It was only the second time a drone had been used for this kind of inspection, which usually required a climb, rappelling, binoculars and a heavy scaffold build.

“Traditionally, this inspection would require four to six weeks of on-site time. The Exelon Clearsight team performed the inspection in less than two weeks with only four people,” Exelon Clearsight said in its case study.

Flyability’s latest software update allows users to create basic, 3D models in real time and Dukowitz says other upgrades are in the pipeline.

Next step

Drones are already taking the human risk out of the measurement of radiation dose and location, and hard-to-reach visual inspections, by assigning the work to just one operator and a subject matter expert (SME), however the next step will be leaving the machine explore a given plant almost completely autonomously.

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) evaluates various drone technologies, usually off-the-shelf and commercially available with modifications for their use in nuclear power stations. One of the latest models comes with the LIDAR autonomous guidance system.

“Drones have been used inside nuclear power plants for several years, however they needed to be controlled by an operator. This reduced the benefits of drones in situations where jobs needed to be done in high radiation, high dose areas as an operator was still needed close by. Also, remotely operating drones can be a difficult task,” EPRI said in an emailed response to questions.

Aside from the benefits from not needing a controller nearby – handy when dealing with highly contaminated or enclosed spaces – automatization also means less in-air collisions, a sure way of losing an expensive piece of machinery in a hard-to-reach corner of a plant.

Full autonomy, however, will need more testing.

“Autonomous drones will need to continue to be demonstrated to be safe to operate in nuclear power plant environments without impacting plant equipment and plant personnel. Adjustments may be needed to allow the drones to operate in smaller spaces safely, to operate without spreading contamination, operate for longer missions (i.e., longer battery life), operate in high temperature/high radiation conditions, etc,” EPRI says.

By Paul Day