Spot takes nuclear O&M to parts other robots cannot reach

Boston Dynamics’ four-legged robot Spot walks like a living quadruped, has a small footprint that won’t churn up dust, is easily hosed down and cleaned and may soon be in every nuclear engineer’s toolbox, say those in the industry who have worked with it.

Related Articles

The basic package for the robot, which can be seen in action here, will set you back $74,500, but its ability to traverse rough terrain that would leave most people with a twisted ankle and its easy-to-use interface means its utility within the nuclear power operations and maintenance industry is difficult to ignore.

“At first I didn’t get it. But when we saw it, it was a real step change,” says Guy Burroughes senior Robotics and Software Engineer at the UK Atomic Energy Authority’s (UKAEA) RACE (Remote Applications in Challenging Environments).

The UKAEA is Britain’s national laboratory for developing fusion energy and it has developed advanced robotic systems for working inside fusion devices. RACE received two Spots to play with in June, though the COVID restrictions delayed their unboxing.

“Its mobility is impressive. Wheels are good, but often the nuclear environment is a very human environment because that’s what plants have been designed for; there are stairs, there’s holes in the floor, a slight lip on the step... it would take a very complicated tank to go upstairs but Spot doesn’t even notice it,” says Burroughes.

The robot’s cost includes training, but Boston Dynamics found that sending company experts along with each dog-in-a-box was not always needed.

“For the initial 10-20 customers, we dedicated a day for training for people to operate the robot. But very quickly we realized that wasn’t necessary,” says Michael Perry, Vice President at Business Development at Boston Dynamics.

“We created a very simple user interface and in trade shows and conferences we can hand the controls to somebody and they are able to get the robot to perform basic missions within seconds.”

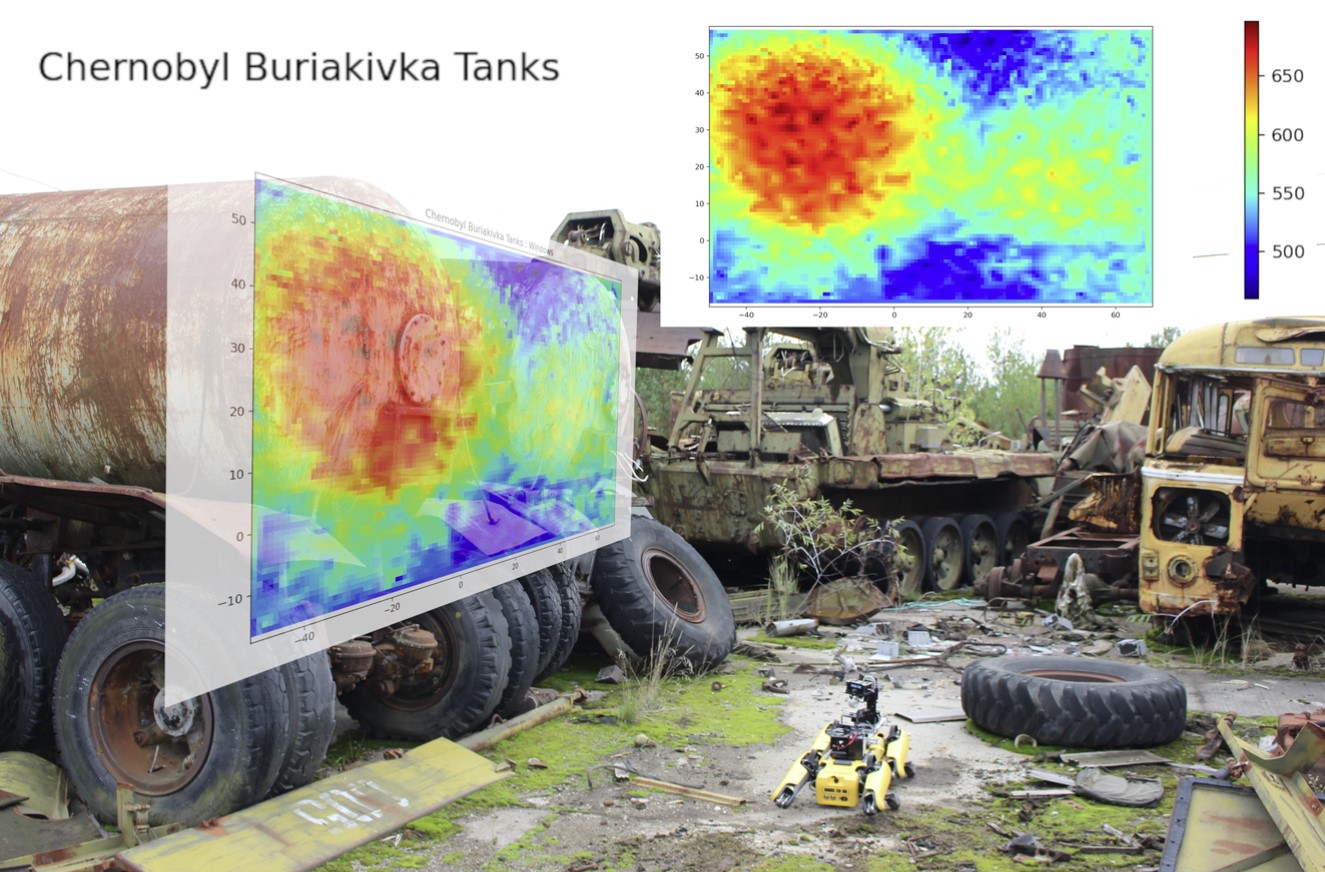

Spot scans vehicles in Chernoyl's Exclusion Zone (Source: University of Bristol)

More than just a drone

Spot is not unlike a drone, in that it is can be controlled from a tablet from a distance and can reach areas that are difficult for engineers and researchers, however there are some key differences, Perry notes.

It can carry up to 16 kilos, a much heavier payload capacity than even the most robust drones. It can reach areas a drone, often restricted by limited lines-of-sight, cannot, and navigate more confined areas and it has a battery life of around 90 minutes walking time per charge. When done, it finds it way back to its plate and settles down to recharge.

Spot has already found jobs outside of the nuclear decommissioning world, including tunnel inspector, looking for stress factors that may cause a cave in within the mining industry, as a repeated data collector on construction sites, and taking 360-degree photos or laser scans to give real time progress monitoring.

“Somebody would typically walk around with a checklist, checking things off, but unfortunately there’s a high error rate because you’re checking a hundred thousand points of inflection with just visual sensing. The other challenge is it’s expensive to do that sort of inspection work and most can’t afford to do that more than once a quarter. If you have Spot on site, you can do it every day,” says Perry.

Universal Studios has even dressed up a Spot in cyber-punk gear at one of their amusement parks in Orlando to entertain the crowds while they’re waiting in line.

In early December, Atkins Nuclear Secured, a member of the SNC-Lavalin Group, formed an agreement with Boston Dynamics to distribute Spot.

Atkins says it will have two business offerings, including 1) Selling the robot to a client, customized to the client’s needs, and providing operators, training and maintenance and; 2) Selling services which rely on Spot to perform the work, such as performing a site radiation survey.

“We believe we’ll have a number of demonstrator Spots at strategic market locations across our global nuclear business in the next year or two. Our hope is to have the first field unit sold/delivered by the end of 2021,” says Brad Bowan, Atkins Fellow and Senior Vice President of Engineering and Technology in an emailed response to questions.

Field trip

After several months of putting its two robots through the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)’s suite of standard tests for Unmanned Ground Vehicles and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, the RACE team gave one robot dog to researchers at the University of Bristol to take to Chernobyl.

The accident at Chernobyl’s reactor 4 in 1986 resulted in hundreds of tons of highly contaminated debris to be spread around the site and the surrounding countryside, clean up of which is ongoing.

Reactor 4 was, eventually, sealed off from the rest of the plant in what became known as the sarcophagus, a protective covering that was further enclosed in 2017 by a larger enclosure. The area contains the main radioactive hazard, the melted down part of the reactor now known as the Elephant’s Foot, while allowing for removal of reactor debris.

The clean up task, which includes thousands of vehicles which became highly contaminated after the explosion and left in a field near the site known as the Exclusion Zone, is scheduled for completion by 2065.

“We did a lot of tests outside, using all of its GPS capabilities, but one of its benefits is that it can learn its own path, undertaking characterization activities autonomously… one of these outside activities was to map the very radioactive ‘hot particles’,” says Royal Academy of Engineering Research Fellow at the School of Physics at the University of Bristol Peter Martin.

“We were able to survey a 200 metre by 200 metre square very quickly. We sit in the back of a van on a freezing cold day, send the robot out, geofence the survey area, go and have a cup of coffee while it’s doing its work. It’s possible to do it a few times, at different angles, in different ways and it can survey a flat or grassed area and find these hot radioactive particles that are distributed on the ground.”

The robot’s light steps stir up a very small amount of radioactive dust and soil that has been collecting, especially under the Chernobyl reactor 4 sarcophagus, where very few people have been sent due to contamination levels. Any workers sent in are first heavily suited to protect them from the radiation and then subsequently given extended duties away from radiation to balance their annual dose.

“What’s inside is largely unknown. They sent robots in a few years ago, but the images are very low resolution. Stuff has degraded, dust has moved around in the plant. That mapping is something we hope to go back to do,” says Martin.

If Spot became very contaminated, its relatively simplicity meant that a session in the car park with Decon 90 detergent and a hose would be enough to clean it down and remove radioactive materials.

Martin’s team has been invited back to Chernobyl to help map the new safe confinement before large cranes are brought in to start dismantling the sargophogus.

Spot, meanwhile, is still growing. For an around an extra $50,000, The unit comes with lidar – a radar system that uses lasers instead of sound – and its next iteration will be fitted with an arm strong enough to carry a handheld XRF unit.

“In terms of the end game, we believe the potential for these types of robots is limited only by our imagination and the mechanical limitations of the robot,” such as battery life and payload capacity, says Atkin’s Bowan.

By Paul Day